When something goes wrong in healthcare, one of the first responses is reassuring.

"We have the data."

The implication is clear: whatever happened, we'll be able to reconstruct it. The record will tell us what we need to know. The truth is in there somewhere.

Often, it isn't. Not because information is missing — but because information is not the same thing as evidence. And the difference only becomes visible when accountability is questioned.

Data Is Not Evidence

Healthcare systems are rich in data. We record observations, results, notes, messages, timestamps, and codes. We can usually produce a detailed timeline of events. Compared to twenty years ago, visibility has improved dramatically.

But evidence is not just a list of things that happened.

Evidence is information that can answer specific questions under scrutiny. Questions like: Who was responsible at that moment? What obligations were active? Which rules applied then, not now? What should have happened next?

Most healthcare data cannot answer those questions reliably. We know what occurred, but not what was expected. That gap — between event and expectation — is where accountability breaks down.

Data vs Evidence

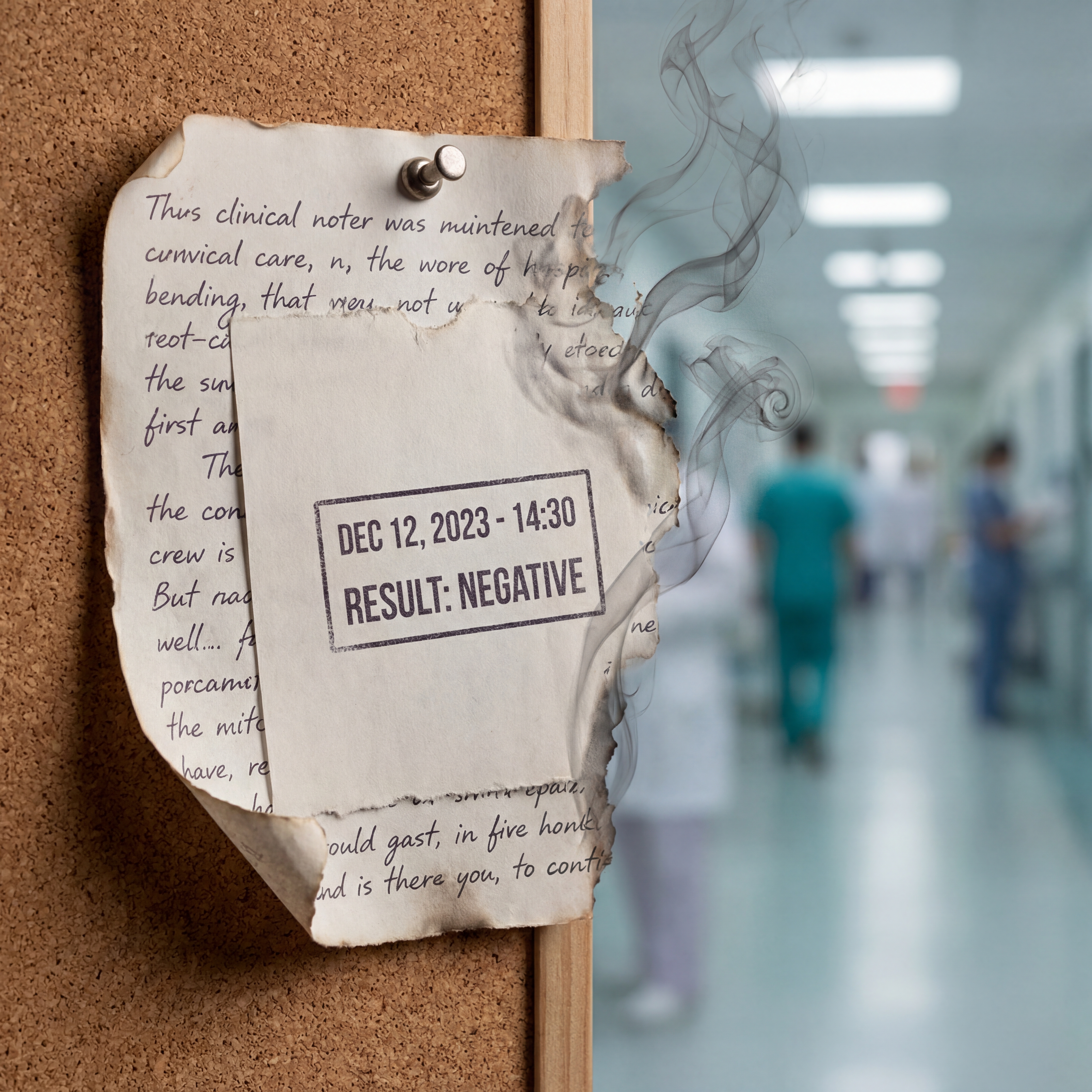

A blood test result is data. The result plus knowledge of who ordered it, why, who was responsible for acting on it, within what timeframe, and what should have happened if it was abnormal — that's evidence. The first survives indefinitely in the record. The second is often lost within days.

Context Evaporates

Evidence is contextual by nature. A result only has meaning in relation to who ordered it, why it was ordered, who was responsible for acting on it, and within what timeframe. A clinical note only has evidential weight if we know whether it represented advice or instruction, whether responsibility transferred with it, whether the recipient was obliged to act or merely informed.

That context is often implicit at the time. Clinicians understand it socially and professionally. In the moment, everyone knows what's expected. The consultant knows the GP will handle the follow-up. The GP knows the patient will return if symptoms worsen. The patient knows someone is watching.

But none of this is captured structurally. It exists in professional understanding, in local custom, in the relationships between specific people who happen to be working that day.

As time passes, context evaporates. What felt obvious on the day becomes ambiguous weeks later. What was "clearly being monitored" becomes unclear once the people involved have moved on, rotated, or left. The consultant who "obviously" expected the GP to act has moved to another trust. The GP who "knew" to follow up has retired. The understanding they shared is gone.

The data remains, but the meaning is gone.

The Audit Illusion

Healthcare audits often give the impression of rigour. We can show when something was recorded, who entered it, where it appears in the system. We can produce comprehensive timelines. We can demonstrate that policies existed, that training was completed, that systems were in place.

But this creates an illusion of certainty.

In many post-incident reviews, the hardest questions are not about missing data. They are about interpretation. Was this result still actionable at that point, or had the window closed? Had responsibility already transferred, or was it still with the original clinician? Was monitoring still active, or had it ended without anyone recording that it had ended? Should someone have intervened — or was the obligation no longer theirs?

These questions cannot be answered from timestamps alone. They require understanding of intent, obligation, and expectation — none of which are reliably preserved.

Auditors end up reconstructing intent from artefacts that were never designed to carry it. They piece together what must have been meant from what was written. They infer responsibility from role descriptions and professional norms. They make assumptions about what reasonable clinicians would have understood.

The more time has passed, the more that reconstruction relies on assumption rather than evidence. And the more room there is for reasonable people to disagree about what really happened.

Responsibility and Evidence Are Inseparable

In the previous article, I argued that responsibility is the missing primitive — the thing healthcare systems don't explicitly model. That matters here because evidence only works if responsibility is clear.

Without knowing who was responsible at a given moment, evidence becomes narrative rather than proof. Different readers can interpret the same record in different ways, each plausibly, depending on the responsibility model they assume.

Consider a discharge summary that says "GP to monitor renal function." Is that a transfer of responsibility, or simply information sharing? Does the GP now own the monitoring obligation, or is this advisory? If the patient deteriorates three weeks later, who failed?

The data doesn't tell you. The words are the same regardless of interpretation. Only the responsibility model — which was never recorded — determines accountability.

This is why serious incidents often generate disagreement even among experienced reviewers. The disagreement isn't about the data — it's about the invisible structure that should have governed it.

When responsibility is implicit, evidence is fragile.

Time Is the Enemy

Evidence does not just decay because people forget. It decays because systems are not time-aware in the ways accountability requires.

Healthcare records are excellent at storing events, but they struggle to preserve state. They show that something happened — but not whether it was still true later, whether it expired, whether it was superseded, or whether it depended on conditions that were never met.

Monitoring advice is a good example. A clinician may say, "Keep an eye on this and come back if it worsens." At the time, that advice is clinically sensible. It reflects appropriate clinical judgment. The patient leaves with a clear instruction.

But nothing in the system records how long the monitoring window lasts. Is it a week? A month? Indefinitely? Nothing records what "worsening" means operationally — which symptoms, how severe, how quickly. Nothing records who is responsible for noticing if the patient doesn't return. Is it the patient's responsibility to re-present? The GP's responsibility to follow up? The original clinician's responsibility to check?

Weeks later, when harm has occurred, the advice is still visible in the record. The words haven't changed. But what is missing is the evidential structure that would show whether an obligation was still active, whose obligation it was, and what should have triggered escalation.

The data survived, but the evidence didn't.

Retrospective Reconstruction Is Not Enough

Healthcare often relies on retrospective evidence. We review incidents. We produce reports. We identify lessons. We update guidance. Root cause analysis has become a discipline in itself.

All of this is valuable — but it comes too late for the patient involved. The learning happens after the harm. The clarity emerges after the confusion has done its damage.

More importantly, retrospective reconstruction is a poor substitute for real-time clarity. If evidence only becomes coherent after harm has occurred, it has failed in its most important role. Evidence should enable intervention, not just explanation.

In other safety-critical industries, evidence is designed to be durable under scrutiny before something goes wrong. Aviation systems don't wait for a crash to determine who was responsible for a handover. Financial systems don't reconstruct trade ownership after a settlement failure. The evidence exists in real time because accountability requires it.

Healthcare has not yet made this shift. We still assume that if we record enough data, evidence will emerge when needed. It doesn't work that way.

A Structural Problem

It's tempting to see evidence decay as a documentation issue. Write better notes. Be clearer about expectations. Record more detail about who is responsible for what.

But more data does not create better evidence if the underlying structure is missing.

Evidence decays because:

- Responsibility is implicit rather than recorded.

- Time is not modelled — obligations don't have expiry dates, conditions don't have triggers, monitoring windows don't have boundaries.

- Obligations are conditional but undocumented, existing only in the professional understanding of people who may no longer be available to explain them.

- Organisational boundaries fracture context, with each organisation seeing only its portion of a story that only makes sense whole.

These are design problems, not behavioural ones. They cannot be solved by asking clinicians to document more carefully. No amount of conscientious documentation can compensate for infrastructure that does not know how to preserve meaning over time.

What Survives Scrutiny

When we look closely at post-incident investigations, a pattern emerges.

Timestamps survive. Raw results survive. Recorded actions survive — the mechanical trace of what happened. Intent, obligation, accountability, expectation — the human structure that gave those actions meaning — these fade away.

And those are the things that matter most when we ask not just what happened, but why no one intervened.

Our systems remember the past well enough. What they can't do is preserve the present in a form that remains meaningful later. Until we can preserve responsibility and context as first-class elements of the record, data alone will continue to give us confidence without certainty.

Naming the Real Problem

Healthcare has plenty of data. What it lacks is durable evidence — evidence that can survive time, organisational change, and scrutiny without being reinterpreted through hindsight.

This is why learning from harm is so hard. We are trying to learn from artefacts that were never designed to teach us what we most need to know. We reconstruct accountability from fragments. We infer intent from timestamps. We guess at obligation from role descriptions.

If we want safer care, we need to stop assuming that data will turn into evidence when it's needed.

Evidence has to be designed.

Series Complete

This is the final article in the Mind the Gap series.

The Complete Mind the Gap Series

- Mind the Gap #1 — Care Doesn't Fail Where You Think It Does

- Mind the Gap #2 — Handoffs Aren't Moments. They're Risk Surfaces.

- Mind the Gap #3 — Responsibility Is the Thing Nobody Can Point To

- Mind the Gap #4 — Evidence Decays Faster Than We Admit (current)

About this series: The first three articles explored where care fails (the liability gap), how handoffs create risk surfaces, and why responsibility is the missing primitive. This final piece completes the picture: without durable evidence, even good data cannot support accountability. The gap between what we record and what we can prove is where patient safety quietly erodes — and where the next generation of clinical infrastructure must do better. View the full series