There's a question that surfaces in almost every serious incident review.

It's usually asked quietly, somewhere after the timeline has been reconstructed and the actions have been listed.

Who was actually responsible at that point?

Not who was involved. Not who touched the record. Not who might reasonably have been expected to notice something. Who, at that moment, held responsibility — with the authority, obligation, and accountability that word implies.

It's remarkable how often this question is hard to answer.

Responsibility Is Assumed, Not Recorded

Healthcare runs on responsibility. Clinical decisions only make sense because someone is accountable for them. Monitoring only matters if someone is obliged to act on change. Escalation pathways only work if someone owns the duty to escalate.

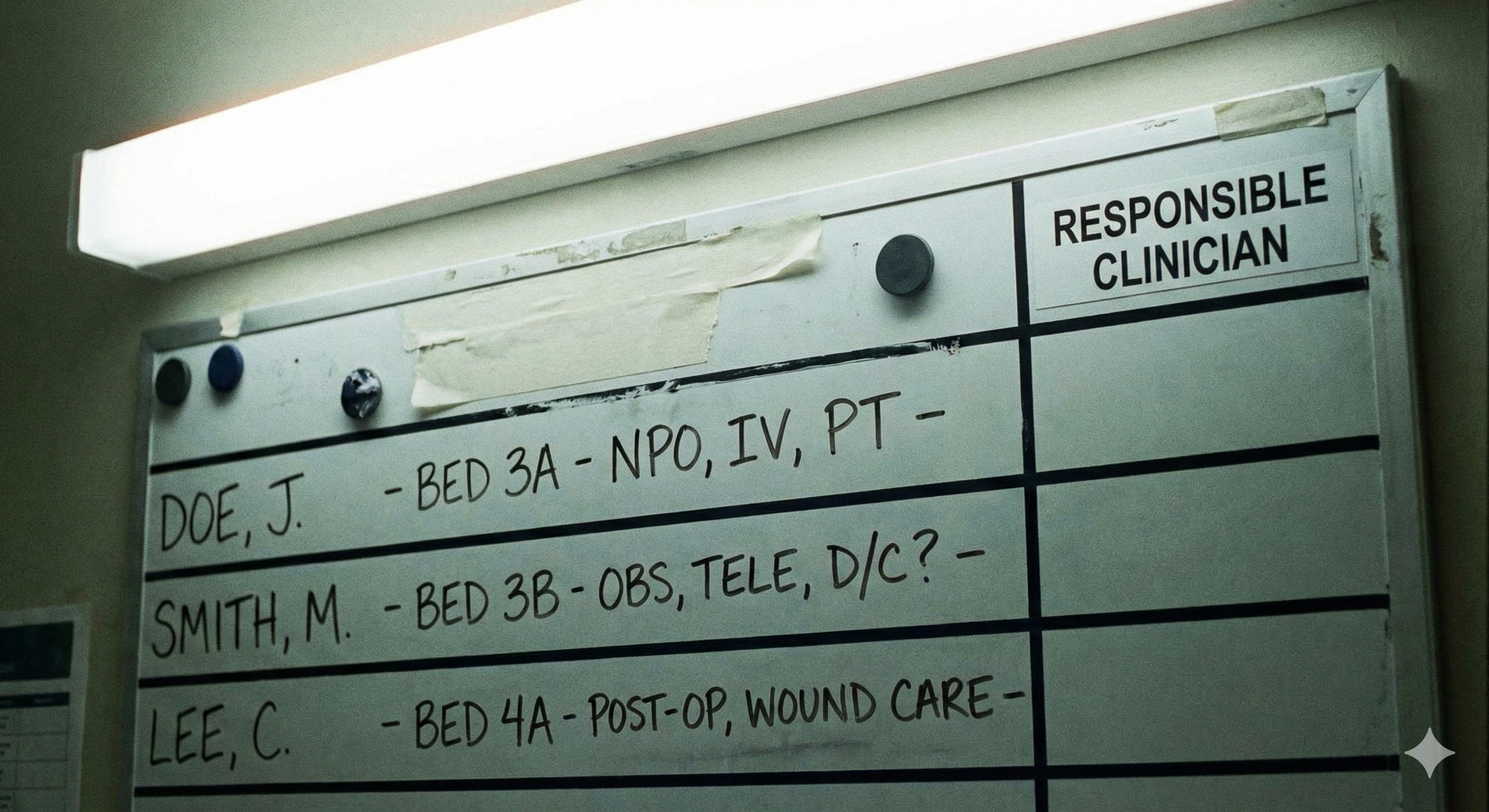

And yet, responsibility itself is rarely explicit. It is inferred from context, assumed based on role, socially negotiated between professionals, or reconstructed after the fact when something has gone wrong. Most systems can tell you what happened. Very few can tell you who was responsible when it mattered.

This is not an oversight. It's a structural blind spot.

Involvement Is Not the Same as Responsibility

One of the reasons this is so difficult is that healthcare routinely conflates involvement with responsibility.

A clinician may review a result, provide advice, offer reassurance, or contribute to a discussion — without holding ongoing responsibility for the patient. Conversely, responsibility may persist even when no active action is being taken. A GP remains responsible for a patient between appointments. A consultant retains responsibility during a monitoring period. The absence of activity does not mean the absence of obligation.

But our systems don't distinguish these states clearly. The medical record shows participation. It does not reliably show obligation.

When responsibility is implicit, it feels obvious in the moment. Everyone involved believes they know who is "looking after this." The problem only becomes visible when something goes wrong and the assumptions no longer line up.

The Reconstruction Problem

This is why post-incident investigations are so often slow and uncomfortable.

Investigators can usually establish which clinicians were involved, what information was available, and what actions were taken. What they struggle to establish is when responsibility transferred, whether it was explicitly accepted, and whether it was still active when the patient deteriorated.

Responsibility is reconstructed indirectly — from timestamps, messages, role descriptions, and professional norms. In other words, from evidence that was never designed to answer the question being asked.

This is why investigations often conclude that "responsibility was unclear." Not because nobody cared, but because the system never made it explicit.

Time Is the Missing Dimension

Responsibility in healthcare is rarely absolute. It is often conditional, partial, shared, or time-bounded.

A clinician may be responsible until a result returns, unless symptoms worsen, provided the patient re-presents if needed, or pending review by another service. These conditions are clinically meaningful — but they are rarely modelled anywhere.

Instead, responsibility is treated as if it were binary. Either you have it, or you don't.

In reality, responsibility behaves more like what engineers call a state machine.

Responsibility as a State Machine

For those unfamiliar with the term: a state machine is a way of modelling something that can exist in different states, with defined rules for how it moves between them. A traffic light is a simple example — it can be red, amber, or green, and there are rules governing when it transitions from one state to another. The light doesn't just "exist" in some vague sense; at any moment, it is in exactly one state, and the system knows which one.

Responsibility in healthcare works the same way, but we don't treat it as such. At any given moment, responsibility for a patient might be:

- Active — someone is currently accountable

- Dormant — responsibility exists but no action is required right now

- Contingent — responsibility will activate if certain conditions are met

- Transferred — responsibility has moved to another clinician or service

- Ended — the episode of care is complete

These aren't abstract categories. They're the actual states that responsibility passes through during any care episode. The problem is that today, those states exist almost entirely in people's heads. They aren't recorded, tracked, or made visible to anyone else in the system.

For the technical reader: this means responsibility could be formally modelled — with defined states, transition conditions, and audit trails. The infrastructure to do this doesn't currently exist in healthcare IT, but there's nothing conceptually preventing it. The gap is architectural, not theoretical.

Organisational Boundaries Make This Worse

Responsibility ambiguity is present even within single organisations. But it becomes far more dangerous when care crosses boundaries.

When responsibility moves between hospital and primary care, between GP and community services, between NHS and private providers, or between physical and virtual care models, there is rarely a shared mechanism for explicitly transferring it.

One organisation may believe responsibility has ended. Another may believe it has not yet begun. The patient assumes continuity.

Each belief can be reasonable. Taken together, they are unsafe.

Because organisational boundaries are administrative constructs, not clinical ones, responsibility often falls into the gaps between them. The boundary exists on paper. The risk exists in real life.

Shared Records Don't Solve This

It's tempting to assume that better information sharing will resolve responsibility ambiguity. If everyone can see the same record, surely responsibility becomes clearer?

In practice, the opposite often happens. Shared records improve visibility, but they blur ownership.

When everyone can see the data, it becomes easier for everyone to assume that someone else is acting on it. The record answers the question "what is known?" It does not answer "who is obliged to act, right now?"

This is the category error at the heart of much digital transformation in healthcare. We have invested heavily in moving information and assumed that accountability would move with it.

It doesn't.

Information can be copied. Responsibility cannot.

Monitoring Without Ownership

One of the clearest manifestations of this problem is monitoring.

A patient is told to watch symptoms and return if they worsen. A test result is "probably fine" but worth keeping an eye on. A follow-up is suggested but not scheduled.

Clinically, this makes sense. Structurally, it creates a responsibility vacuum.

The patient believes they are still under care. The clinician believes responsibility will reactivate if certain conditions are met. The system records the encounter as complete.

Responsibility exists — but only conditionally, and only implicitly.

When deterioration happens slowly or ambiguously, there is no clear trigger. No one is alerted that responsibility should have reactivated. And when harm occurs, it is retrospectively obvious what should have happened — but invisible what was supposed to happen at the time.

Not About Blame

Responsibility ambiguity is not caused by careless clinicians. It is not fixed by telling people to be more vigilant.

It arises because healthcare systems were never designed to model responsibility explicitly over time and across boundaries.

In other regulated sectors, this lesson was learned the hard way. Financial services does not rely on professional goodwill to determine who owns a trade at settlement. Aviation does not assume responsibility has transferred because someone sent a message. Energy systems do not treat handovers as complete without explicit acceptance.

Healthcare still does. Not because it is less serious, but because the infrastructure to do otherwise does not yet exist.

Why Naming Responsibility Matters

As long as responsibility remains implicit, healthcare will continue to struggle with unsafe handoffs, fragile monitoring, slow incident reconstruction, and repeated harm without clear learning.

We cannot fix what we cannot name.

Responsibility is the thing nobody can point to — until something goes wrong. Then everyone is forced to point to it, backwards, with incomplete evidence and uncomfortable assumptions.

If we want safer care, we need systems that can answer a simple question in real time: Who is responsible right now — and under what conditions?

Until then, responsibility will continue to exist everywhere in practice, and nowhere in structure.

And the gap will remain.

The Complete Mind the Gap Series

- Mind the Gap #1 — Care Doesn't Fail Where You Think It Does

- Mind the Gap #2 — Handoffs Aren't Moments. They're Risk Surfaces.

- Mind the Gap #3 — Responsibility Is the Thing Nobody Can Point To (current)

- Mind the Gap #4 — Evidence Decays Faster Than We Admit

This is part of the Mind the Gap series — exploring where clinical safety actually fails and what infrastructure would make it safer. View the full series