At 16:47 on a Friday afternoon, a hospital discharge coordinator completes a discharge summary, uploads it to MESH, updates the bed management system, and marks the patient as discharged. The bed is freed. The patient leaves.

At the GP practice, the discharge summary arrives in the workflow queue. It sits there until Monday morning, when a practice administrator triages the incoming documents. The GP reviews it on Tuesday. By Wednesday, they have actioned the medication changes and booked the follow-up blood test.

For roughly 90 hours, this patient had no named responsible clinician. The hospital had discharged them. The GP had not yet received, reviewed, or accepted the clinical information. The patient existed in a governance vacuum - clinically unowned, administratively invisible, and structurally unprotected.

This is not an edge case. This is how the system works. And it is the single most dangerous pattern that boundary governance must address.

This example uses an NHS discharge because it is universally recognised. But MVRT failures are not an NHS problem. They are a boundary problem. A private hospital discharging a patient to their GP faces the same structural gap. A private insurer's pre-authorisation process that delays a clinically urgent procedure creates the same governance vacuum. A telehealth platform routing a patient from a virtual consultation to a private specialist creates the same unowned interval. The principle applies wherever clinical responsibility crosses between organisations - regardless of whether those organisations are public, private, or a mix of both.

The principle healthcare violates

Every other safety-critical industry solved this problem decades ago. In aviation, an aircraft transiting from one air traffic control sector to another cannot complete the handover until the receiving controller electronically verifies and accepts responsibility. The infrastructure structurally prevents the existence of an unowned aircraft. A pilot cannot be told "you're now in London Control's airspace" while London Control is unaware of their existence.

In maritime operations, a vessel transiting between port authorities follows a defined protocol where the receiving authority acknowledges the vessel's entry, confirms its identity, and accepts monitoring responsibility. The handover is bilateral, logged, and time-stamped.

In nuclear power generation, shift handovers follow protocols where the outgoing team cannot leave until the incoming team has physically confirmed their understanding of plant status, outstanding actions, and safety-critical parameters.

Healthcare routinely violates the principle that underpins all of these systems: that responsibility transfer must be explicit, bilateral, and confirmed before it is complete.

What is Minimum Viable Responsibility Transfer (MVRT)?

MVRT is the clinical governance principle requiring that the transfer of patient responsibility between healthcare organisations must be explicit, bilateral, and confirmed before the handover is complete. Derived from safety-critical handover protocols in aviation, maritime, and nuclear industries, MVRT defines the minimum conditions that must hold at any organisational boundary before clinical responsibility can safely cross. Without MVRT, patients exist in governance vacuums - clinically unowned, administratively invisible, and structurally unprotected.

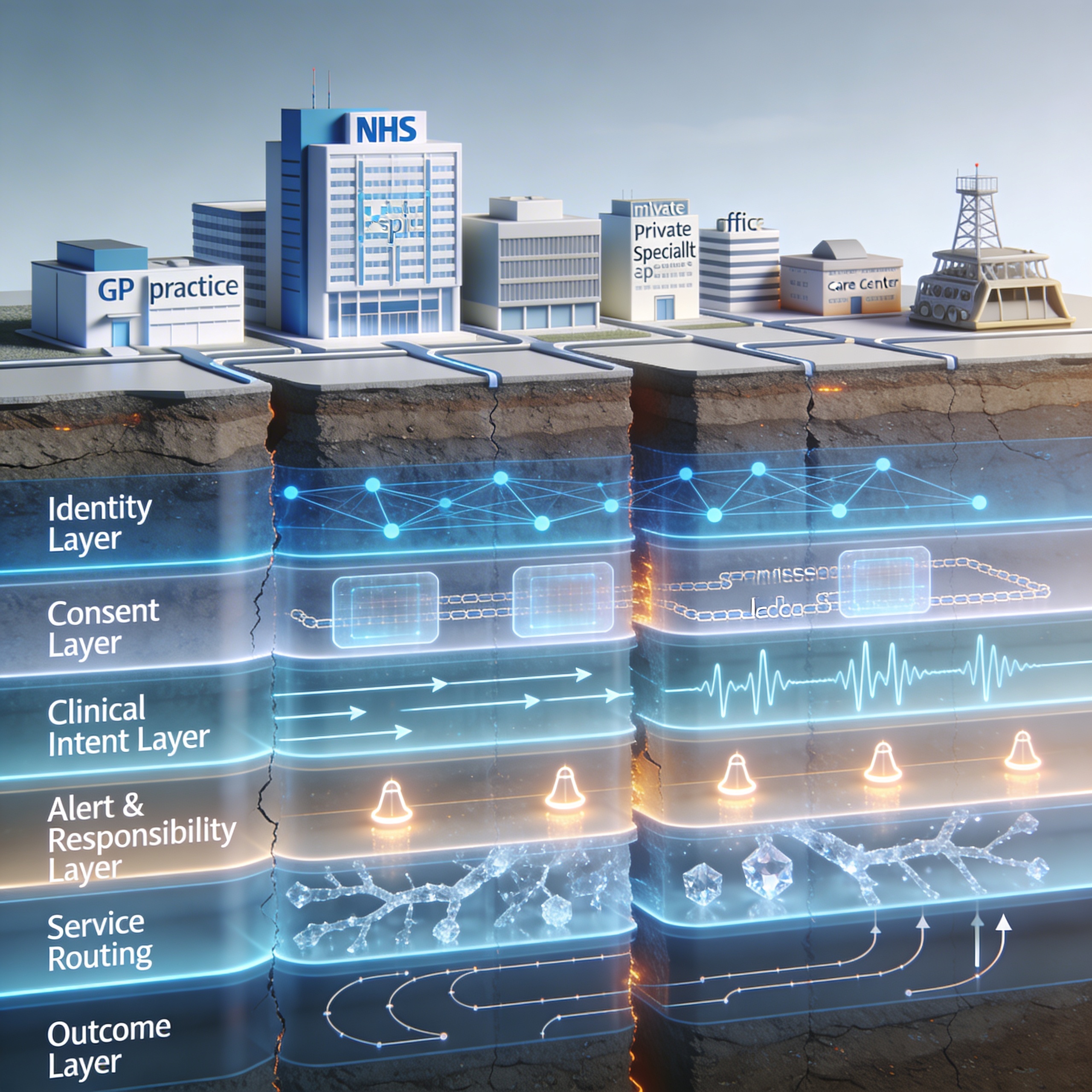

We have formalised this principle. We call it Minimum Viable Responsibility Transfer - MVRT - and it sits at the centre of our Seven Flows Boundary Governance Audit as the normative control for the fifth and most critical flow: Alert & Responsibility. In our scoring model, a boundary that cannot demonstrate explicit, bilateral responsibility transfer cannot score above Level 2 on Alert & Responsibility - regardless of how well everything else functions. And because our cascading failure logic caps downstream scores when upstream flows fail, an MVRT failure structurally limits the Outcome score as well. If no one has formally accepted responsibility, there is no accountable party from whom outcome data can be expected.

Where patients fall through: seven boundaries examined

MVRT failures are structurally embedded in how healthcare boundaries operate today - in the NHS, in private healthcare, and at the interfaces between them. Consider seven patterns that recur across the system.

1. The Hospital Discharge Boundary

This is the most universal example because it affects millions of patients annually. The hospital's system marks the discharge as complete the moment the summary is generated. The GP's system does not flag the patient as received until a clinician reviews the document. Between these two system events, the patient is clinically unowned. Under our scoring model, a discharge-to-GP boundary like this would score 1 out of 4 on Alert & Responsibility. The infrastructure actively permits the gap - a discharge can complete without confirmed receipt. This is not a process failure. It is a design failure.

2. The GP Referral Boundary

A GP refers a patient to a specialist. The referral enters the receiving Trust's booking system. But the specialist has no obligation to confirm receipt to the referring GP, no obligation to confirm they have reviewed the clinical information, and no obligation to notify the GP if they decide the referral is inappropriate. Under our methodology, the Clinical Intent flow - does the specialist know why the patient was referred and what is expected? - would likely score Level 2 at this boundary (the referral letter exists but lacks structured action coding). Alert & Responsibility would score Level 1 (no confirmed acceptance). The cascade effect is significant: because Clinical Intent is below Level 2, our model caps both Alert & Responsibility and Service Routing, reflecting the structural reality that you cannot responsibly accept a patient whose clinical purpose you don't fully understand.

3. The Telehealth Boundary

A patient consults a virtual GP through a digital platform. The virtual GP identifies a need for physical examination and generates a referral. That referral crosses from the digital platform's governance framework to the NHS Trust's governance framework. The platform marks the patient as referred. But at the moment of transfer, the patient has left the platform's clinical responsibility without entering the Trust's. This boundary carries additional complexity because it crosses what we call a constitutional boundary - the digital platform and the NHS Trust operate under different legislation, different regulators, and different institutional orientations. Our Constitutional Transition Matrix rates Digital-to-NHS crossings as HIGH risk, which triggers enhanced governance requirements in our assessment framework: explicit patient notification of the transition, independent lawful basis establishment by the receiving organisation, and MVRT enforcement.

4. The Diagnostic Results Boundary

A GP orders blood tests through a diagnostic provider. The results are sent back electronically. But the diagnostic provider's responsibility ends at transmission. The GP's responsibility begins at review. If the results contain a critical finding - and they sit in a workflow queue over a bank holiday weekend - the patient is clinically unowned for the duration. Under our framework, the Provenance flow (can the GP verify the source and integrity of the result?) would likely score reasonably well at this boundary. But Alert & Responsibility would fail because there is no mechanism to confirm that a critical result has been seen and actioned within a clinically safe timeframe. The system permits critical information to sit unacknowledged.

5. The Mental Health Crisis Boundary

A patient presents at A&E in mental health crisis. The A&E team stabilises them and refers to the crisis resolution home treatment team. The patient is discharged from A&E with a plan to be contacted by the crisis team within 24 hours. If the crisis team is at capacity, if the referral doesn't reach them, if the patient's phone number is wrong - the patient is discharged from one service without being received by another. This boundary often crosses a constitutional domain as well: the A&E may sit under one Trust, the crisis team under another. In mental health, the MVRT gap can be fatal. This is why Alert & Responsibility is designated as a critical flow in our methodology - alongside Identity, it is one of two flows whose failure floors the overall boundary governance rating to "Not Assured" regardless of performance elsewhere.

6. The Insurer Pre-Authorisation Boundary

A private patient requires an urgent procedure. The clinician submits a pre-authorisation request to the insurer. The insurer's clinical review team assesses the request against policy terms. But the insurer's processing timeline and the patient's clinical timeline may diverge. The clinician is waiting for authorisation. The insurer is processing. The patient sits in a gap between clinical need and administrative process. If the insurer requests additional clinical information and the request is routed to the wrong person, the authorisation stalls indefinitely. Under our framework, this boundary would expose an MVRT failure: the clinician has released the decision to the insurer, the insurer has not confirmed acceptance within a clinically safe timeframe, and no escalation pathway exists. This is a Private-to-Insurance constitutional crossing - rated HIGH on our Transition Matrix - and it occurs entirely outside the NHS.

7. The Post-Acquisition Integration Boundary

When a PE firm acquires a healthcare provider and integrates it with an existing portfolio company, boundaries that were previously external become internal. But the governance obligations don't change - CQC registrations remain separate, clinical governance structures remain distinct, data controller responsibilities remain independent. The acquirer often assumes that corporate integration resolves governance. In practice, it makes it invisible. Referral pathways that previously had formal data sharing agreements become informal internal processes. Responsibility transfer that was at least documented in external governance becomes assumed. Under our scoring model, these post-acquisition boundaries are particularly vulnerable to MVRT failure because the informality of corporate integration actively suppresses the governance mechanisms that previously existed.

Why existing governance doesn't catch it

Clinical governance frameworks within organisations are often sophisticated. Hospitals have mortality and morbidity meetings, clinical audit programmes, incident reporting systems, and risk registers. GP practices have significant event analysis, complaints processes, and QOF measures.

But these governance mechanisms operate within the organisation. They assess what happens after the patient arrives, not what happened in the gap before they arrived. A hospital's clinical governance will review a patient who deteriorated after admission. It will not systematically review patients who deteriorated between being referred and being seen - because it may never know they existed.

This is the Outcome flow problem - the seventh of our Seven Flows. After a patient crosses a boundary, does the originating organisation learn what happened? For the vast majority of healthcare boundaries today, the answer is no. The boundary is a one-way door. The patient goes through. The originating organisation never learns whether the referral resulted in good care, delayed care, or harm. Without this feedback loop, the same MVRT failures repeat indefinitely because no governance system captures them.

CQC inspections reinforce this pattern. Regulation 12 requires safe care. Regulation 17 requires good governance. But both are assessed at the provider level. An inspection of Provider A examines Provider A's governance. It does not examine the boundary between Provider A and Provider B. Our methodology addresses this directly - every finding traces to a specific CQC Regulation, showing precisely where Regulation 12 or 17 obligations are engaged at the boundary but unmet. This gives organisations evidence grounded in the regulator's own framework.

DCB 0129 and 0160 create a further gap. The clinical safety standards require hazard logs to document clinical risks from health IT. But the hazard log template does not include boundary-specific risks - the risks of transmission failure, identity loss, implicit responsibility transfer. The CSO's personal liability extends to the safety case, but the safety case doesn't cover what happens between organisations. Our audit is designed to help CSOs understand the scope of their boundary-specific obligations and provide the evidence base for extending their hazard logs to the boundaries where risk is highest.

Why MVRT Is Critical for Clinical Safety Officers (CSOs)

If you hold a CSO role under DCB 0160, your personal professional liability covers the clinical safety case for your organisation's health IT deployments. But that safety case almost certainly does not address what happens when clinical responsibility crosses to another organisation. MVRT failures - implicit handovers, unconfirmed receipts, unowned patients - create hazards that fall within your accountability but outside your current hazard log.

Our methodology for Clinical Safety Officers is designed to give you boundary-specific risk assessments with statutory traceability to DCB 0160, CQC Regulation 12, and UK GDPR Article 6 - evidence that can be added directly to your hazard log.

What MVRT requires in practice

MVRT is not a technology product. It is a governance principle that infrastructure must enforce. Our methodology assesses every boundary against five specific MVRT requirements:

Explicit, bilateral declaration. The sending organisation explicitly releases responsibility. The receiving organisation explicitly accepts it. Neither party can unilaterally declare the transfer complete. This is the aviation principle: the handover is not complete until both sides confirm. In our scoring, this is the threshold for Level 3 on Alert & Responsibility. Without bilateral declaration, a boundary cannot achieve "Managed" status.

Infrastructure enforcement. The transfer cannot complete without bilateral acknowledgement. This is a system design requirement, not a process requirement. A discharge that can be marked "complete" before the GP has acknowledged receipt is a system that permits MVRT failure by design. Our technology assessment evaluates whether the infrastructure at each boundary can enforce this - and where it can't, the remediation roadmap specifies what needs to change.

Clinically safe escalation. If acknowledgement is not received within a defined timeframe, the system escalates. The timeframe is clinically determined - hours for acute care, days for routine referrals - and the escalation pathway is pre-defined and tested.

Unowned patient identification. At any point, the system can identify patients who are in transit between organisations with no named responsible clinician. These patients are flagged, visible, and actively managed. They are not invisible.

Auditable governance artefact. Every MVRT event is logged, time-stamped, and traceable. The log feeds into the clinical safety hazard log. MVRT failures are treated as safety events, not administrative inconveniences.

None of this is technically difficult. Electronic acknowledgement systems exist in every other sector. What is missing is the governance requirement - the explicit recognition that responsibility transfer at organisational boundaries is a patient safety issue that requires structural enforcement.

What a boundary assessment would show

To illustrate what the methodology produces, consider how a typical discharge-to-GP boundary would score.

Example Scorecard: Discharge-to-GP Boundary

Identity: Level 3 - NHS number verified, PDS lookup confirmed

Consent: Level 2 - National Data Opt-Out checked but no boundary-specific DPIA

Provenance: Level 2 - Author identified but no structured metadata

Clinical Intent: Level 2 - Diagnosis stated but follow-up actions in free text

Alert & Responsibility: Level 1 - MVRT failure, no confirmed receipt

Service Routing: Level 2 raw, cascade-adjusted to Level 1

Outcome: Level 1 - No structured feedback from GP to Trust

Overall: Not Assured. Average 1.7/4. Critical flow at Level 1.

That scorecard would tell a board, a CSO, or a commissioner more about the safety of that boundary than any amount of internal governance reporting. And because every finding traces to specific statutory obligations - CQC Regulation 12 for safe care, DCB 0160 for clinical safety assurance, UK GDPR Article 6 for lawful basis at the boundary - the evidence is immediately usable for regulatory purposes. See a full sample scorecard.

The human cost of assumption

The reason this matters is not regulatory compliance. It is not governance elegance. It is that patients come to harm in the gaps between organisations, and the system is structurally designed to not notice.

When a patient deteriorates between discharge and GP review, the hospital records a successful discharge. The GP records a new presentation. Neither record captures the failure in the gap. The patient's experience - confusion about who is responsible for their care, uncertainty about whether their medications have been reconciled, anxiety about whether anyone is monitoring their recovery - is invisible to both organisations' governance systems.

When a mental health patient falls between crisis services, the incident may surface as a coroner's inquest. At that point, both organisations produce their records showing their internal governance was followed. The gap between them - the period where the patient was nobody's patient - is the thing that failed. And it is the thing that no existing framework required either organisation to govern.

The shift to integrated care under the Ten Year Plan makes this exponentially more complex. More providers, more boundaries, more transfers, more opportunities for patients to fall into governance vacuums. Without MVRT as a structural principle - assessed, scored, and enforced - integrated care becomes a system optimised for efficiency with a structural blind spot for safety.

The organisations that treat boundary governance as a clinical safety priority - that map their boundaries, score them, identify the MVRT failures, and build the infrastructure to enforce bilateral handover - will be the ones that can demonstrate to CQC, to commissioners, and to patients that their care is governed end-to-end. Not just within the walls of a single building.

Healthcare Boundary Governance Series

- The Governance Gap in the NHS Ten Year Plan & Reforms

- When Your Patient Becomes Nobody's Patient (current)

- The Constitutional Problem in Healthcare Data Sharing

- 70% of NHS Digital Health Has No Safety Assurance

Inference Clinical's Seven Flows Boundary Governance Audit scores MVRT compliance at every organisational boundary, with cascading failure logic that reveals structural dependencies invisible to internal governance. To understand where your patients may be most vulnerable, take the free Boundary Risk Score or book a boundary scoping call.