Key Takeaways

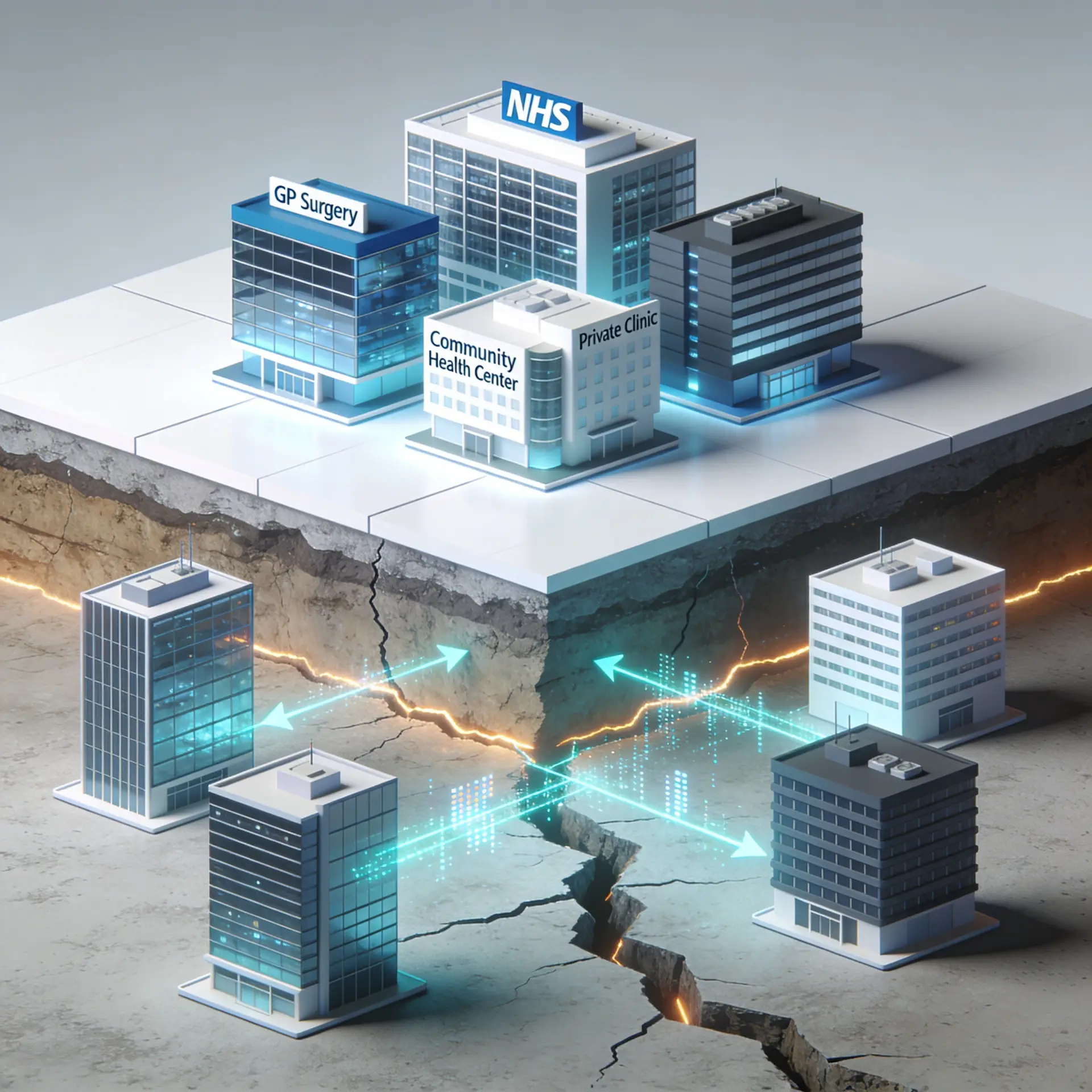

- The NHS Ten Year Health Plan creates Neighbourhood Health Centres, Integrated Health Organisations, and outcomes-based commissioning - each multiplying inter-organisational boundaries where governance must function.

- Co-location does not legally merge data controllers or clinical liability. Informal corridor conversations are still inter-organisational referrals requiring governed responsibility transfer.

- Existing frameworks (CQC, DCB 0129/0160, PSIRF, DSPT) govern internal operations within single organisations, leaving a structural gap at every boundary between organisations.

- The Seven Flows methodology and Constitutional Transition Matrix are designed to assess exactly this gap - with cascading failure logic that reveals structural dependencies invisible to internal governance.

- Private healthcare groups, PE-owned portfolios, and insurer networks face the same boundary governance gap - often with less standardised infrastructure than NHS equivalents.

The NHS Ten Year Health Plan is the most structurally ambitious reform programme since the Health and Social Care Act 2012. It promises Neighbourhood Health Centres, Integrated Health Organisations, outcomes-based commissioning, AI-enabled diagnostics, Foundation Trust reform, and a decisive shift from hospital-centred to community-centred care.

Every one of these reforms creates more organisational boundaries. Not fewer. More.

And not a single element of the Plan addresses how governance works at those boundaries.

At Inference Clinical, we built a methodology specifically for this problem. We call it the Seven Flows Boundary Governance Audit - a structured, statutory-traceable framework for assessing governance at the joins between organisations, not within them. What follows is the analysis that led us to build it.

The analysis begins with the NHS Ten Year Plan because it makes the boundary problem structurally visible. But this is not an NHS-only problem. Private healthcare groups, insurers, diagnostic networks, and digital health platforms all operate across organisational boundaries - and in many cases, those boundaries are less governed than their NHS equivalents, because private sector organisations often lack the standardised governance infrastructure (hazard logs, PSIRF, DSPT) that NHS organisations at least nominally maintain. A PE-owned hospital group with six sites, a diagnostic partnership, an insurer pre-authorisation flow, and a telehealth platform has boundary governance gaps at every join. The regulatory obligations - CQC, DCB 0129/0160, UK GDPR - apply identically whether the boundary is NHS-to-NHS or Private-to-Private.

How the NHS Ten Year Plan multiplies clinical governance boundaries

Consider what the Plan actually proposes. Neighbourhood Health Centres - the Plan's co-located hubs bringing GPs, community services, mental health teams, pharmacists, and voluntary organisations together under one roof - will integrate multi-disciplinary teams. But each of those organisations retains its own CQC registration, its own data controller status, its own clinical governance framework, and its own statutory obligations. Co-location doesn't merge governance. It multiplies the boundaries where governance must function.

Our methodology scores every boundary across seven dimensions - what we call the Seven Flows: Identity, Consent, Provenance, Clinical Intent, Alert & Responsibility, Service Routing, and Outcome. Each flow represents something that must work at every organisational boundary for patient safety to be maintained. In a neighbourhood health centre, every interaction between the GP practice and the community nursing team is a boundary that engages all seven flows. Every referral from the mental health practitioner to the pharmacist is another. A single neighbourhood centre with five participating organisations creates up to ten bilateral boundaries, each requiring governance across seven dimensions.

Integrated Health Organisations (IHOs) - the Plan's proposal for bodies holding single budgets and accountability for defined populations - represent the most radical structural change. But they will deliver care through networks of providers, each with their own constitutional basis. An IHO that commissions mental health services from a private provider, diagnostic imaging from an independent network, and community rehabilitation from a voluntary sector organisation hasn't eliminated organisational boundaries. It has created a web of them.

We map these crossings using what we call the Constitutional Transition Matrix - a framework that identifies the additional governance risk when a boundary crosses between fundamentally different types of institution. An NHS-to-NHS boundary is low risk: same legislation, same regulator, same institutional purpose. An NHS-to-Private boundary is medium-high: different commercial incentives, different regulatory emphasis. A Private-to-Insurance boundary is high: the institutional orientation towards the patient shifts from care to financial risk management. An IHO commissioning across NHS, private, voluntary, and digital providers doesn't just have more boundaries - it has boundaries that cross constitutional domains, each carrying different risk profiles that require different governance responses.

The same structural challenge exists entirely within the private sector. When a private hospital group acquires another provider - as happened with Spire's acquisition of Vita Health Group - boundaries that were previously external (and therefore had at least some formal governance through data sharing agreements and referral protocols) become internal. But the regulatory obligations don't dissolve with the corporate transaction. CQC registrations remain separate. Clinical governance frameworks remain distinct. Data controller responsibilities remain independent. The post-acquisition integration creates internal boundaries with all the governance complexity of external ones, but with the added risk that corporate integration makes them invisible. When a private hospital refers to a diagnostic imaging partner, when an insurer's pre-authorisation process interacts with a provider's clinical workflow, when a telehealth platform routes a patient to a private specialist - each of these is a boundary requiring governance across all seven dimensions, and none of them involves the NHS at all.

The outcome gap the Plan can't answer

The shift to outcomes-based commissioning through Year of Care Payments and capitated budgets demands something that doesn't currently exist: structured cross-boundary outcome data.

This is the seventh of our Seven Flows - Outcome - and it is the flow most likely to score lowest at any given boundary. The question is deceptively simple: after a patient crosses a boundary, does the originating organisation learn what happened? When a GP refers a patient to a specialist, does the GP receive structured outcome data that tells them whether the referral resulted in good care? When a hospital discharges a patient to community services, does the hospital learn whether the discharge plan was followed?

The honest answer, for the vast majority of healthcare boundaries today, is no. The boundary is a one-way door. The patient goes through. The originating organisation never learns the outcome. And without outcome data, two things become impossible: the originating organisation cannot improve its boundary processes (because it has no feedback signal), and outcomes-based commissioning cannot function (because outcomes cannot be attributed across providers).

If an IHO is accountable for population health outcomes, but care is delivered across six providers, who measures the outcome? Who owns the data? Who is responsible when the outcome is poor and the failure occurred in the seam between two providers? The Plan provides no answer because no existing framework poses the question.

Why co-location doesn't solve it

There is an intuitive assumption that bringing services together physically will reduce governance complexity. If GPs, community nurses, and mental health teams share a building, surely the boundaries dissolve?

They don't. Co-location changes the operational experience - clinicians can walk down the corridor instead of sending a referral - but it does not change the legal architecture. The GP practice remains an independent contractor under GMS/PMS. The community nurse remains an employee of the NHS Trust. The mental health team may sit under a different Trust entirely. Each remains a separate data controller. Each has its own CQC registration. Each has its own clinical governance structure.

When the GP asks the mental health practitioner in the next room to review a patient, that is still an inter-organisational referral. The data sharing still requires lawful basis. The responsibility transfer still requires governance. The clinical intent still needs to be communicated. The outcome still needs to be captured.

What changes is visibility. In a co-located setting, the informality of the interaction masks the governance requirement. It feels like a conversation between colleagues. Legally, it is a data transfer between independent controllers with an implicit responsibility handover that no hazard log addresses.

This is where our scoring model reveals something that intuition misses. We apply cascading failure logic: if a boundary scores below Level 2 on Identity, then Consent and Provenance are automatically capped - because you cannot meaningfully verify consent or data provenance if you can't reliably identify the patient at the point of crossing. In co-located settings, Identity would likely score well (clinicians know each other, patients are physically present), but Alert & Responsibility would score poorly because the informality means responsibility transfer is implicit, not documented. And because our scoring model applies a structural dependency - if Alert & Responsibility fails, Outcome is capped - the cascade would reveal that the entire boundary is less governed than it appears.

What existing frameworks actually cover

The NHS has a sophisticated set of governance frameworks. They are not the problem. The problem is their scope.

CQC fundamental standards

- Intended scope:

- Assesses whether a single registered provider delivers safe, effective, person-centred care. Every standard - Regulation 9, 12, 13, 17, 20 - assumes a single registered provider.

- Boundary gap:

- CQC can inspect Provider A. CQC can inspect Provider B. Neither inspection examines the boundary between them. No CQC assessment evaluates how governance functions at the inter-organisational join.

DCB 0129 and DCB 0160

- Intended scope:

- Mandatory clinical safety standards for health IT. Require manufacturers (0129) and deploying organisations (0160) to maintain clinical safety cases and hazard logs. Powerful instruments for internal clinical risk management.

- Boundary gap:

- Operate within the assumption of a single deploying organisation. When a digital health technology operates across an organisational boundary, the standards do not explicitly require the hazard log to address boundary-specific risks - the risks of translation, transmission, and responsibility transfer at the crossing.

PSIRF (Patient Safety Incident Response Framework)

- Intended scope:

- Significant improvement in how organisations respond to patient safety incidents internally. Structures learning responses and compassionate engagement.

- Boundary gap:

- A 2025 study in the Journal of Long-Term Care found PSIRF "does not create a wider policy environment for cross-boundary arrangements that promote cross-system patient safety." Cross-organisational incidents fall between frameworks.

DSPT (Data Security and Protection Toolkit)

- Intended scope:

- Self-assessment by a single organisation of its own data handling, security controls, and information governance practices.

- Boundary gap:

- Does not assess what happens to data after it leaves the organisation. A DSPT-compliant organisation may send data to another DSPT-compliant organisation, but the boundary between them - where data transforms, responsibility transfers, and clinical context may degrade - is unassessed by either toolkit submission.

Each framework is sound within its scope. The gap is structural: none of them addresses the governance of what happens between organisations. This is precisely the gap our Boundary Risk Assessment methodology sits in. Every finding in our framework traces to one of these statutory instruments - CQC Regulation 17, DCB 0160, UK GDPR Article 6, PSIRF - but applies them to the boundary context that the frameworks themselves don't address. We're not inventing new obligations. We're showing where existing obligations already apply but aren't being met.

The regulatory inevitability

The boundary governance gap will be closed. The question is not whether, but how and when.

The Data Use and Access Act 2025 grants binding statutory powers to mandate information standards covering system functionality, interoperability, data portability, and security. These mandates will increase the volume and visibility of data flowing across organisational boundaries, making governance failures more frequent and more consequential.

HSSIB's October 2025 report on PSIRF implementation found that ICBs are supposed to coordinate cross-organisational investigations, but "in reality this support was often not offered or possible." The statutory body responsible for patient safety investigation has identified that the cross-organisational dimension of safety governance is failing. A response will follow.

CQC's evolution towards system-level assessment reflects a growing recognition that quality and safety are properties of systems, not just individual providers. The Well-Led framework's emphasis on governance will increasingly need to account for how organisations govern their interfaces with partners, not just their internal operations.

What we built and why

Our methodology produces a per-boundary, per-flow maturity scorecard with cascading failure adjustments and statutory traceability. For the first time, a board would be able to see that a specific boundary - say, a discharge-to-GP pathway - scores 1 out of 4 on Alert & Responsibility because responsibility transfer is implicit, and that this cascades to cap Service Routing and Outcome scores regardless of how well those flows appear to function in isolation. See a sample scorecard.

The technology assessment evaluates whether the infrastructure at each boundary can enforce the governance requirements programmatically - and produces a funded remediation roadmap using available cloud migration incentives. Governance that depends on humans remembering to follow process will fail at scale. The Ten Year Plan envisions hundreds of neighbourhood health centres, each with multiple organisational boundaries. The infrastructure needs to enforce it.

The organisations that address this now will be the ones that shape the standard. The ones that wait will be retrofitting after a serious incident forces the issue.

Healthcare Boundary Governance Series

- The Governance Gap in the NHS Ten Year Plan & Reforms (current)

- When Your Patient Becomes Nobody's Patient

- The Constitutional Problem in Healthcare Data Sharing

- 70% of NHS Digital Health Has No Safety Assurance

Inference Clinical's Seven Flows Boundary Governance Audit produces a statutory-traceable scorecard for every organisational boundary, with cascading failure logic, constitutional transition analysis, and a funded remediation roadmap. To understand how your boundaries would score, take the free Boundary Risk Score or book a scoping call.