Key Takeaways

- The NHS England neighbourhood health guidelines define six service components but do not describe what must work at the organisational boundaries between the providers delivering them.

- A 2025 BMC Public Health systematic review found neighbourhood models “lack a unified definition and standard framework” — and identified governance only as organisational governance, not boundary governance.

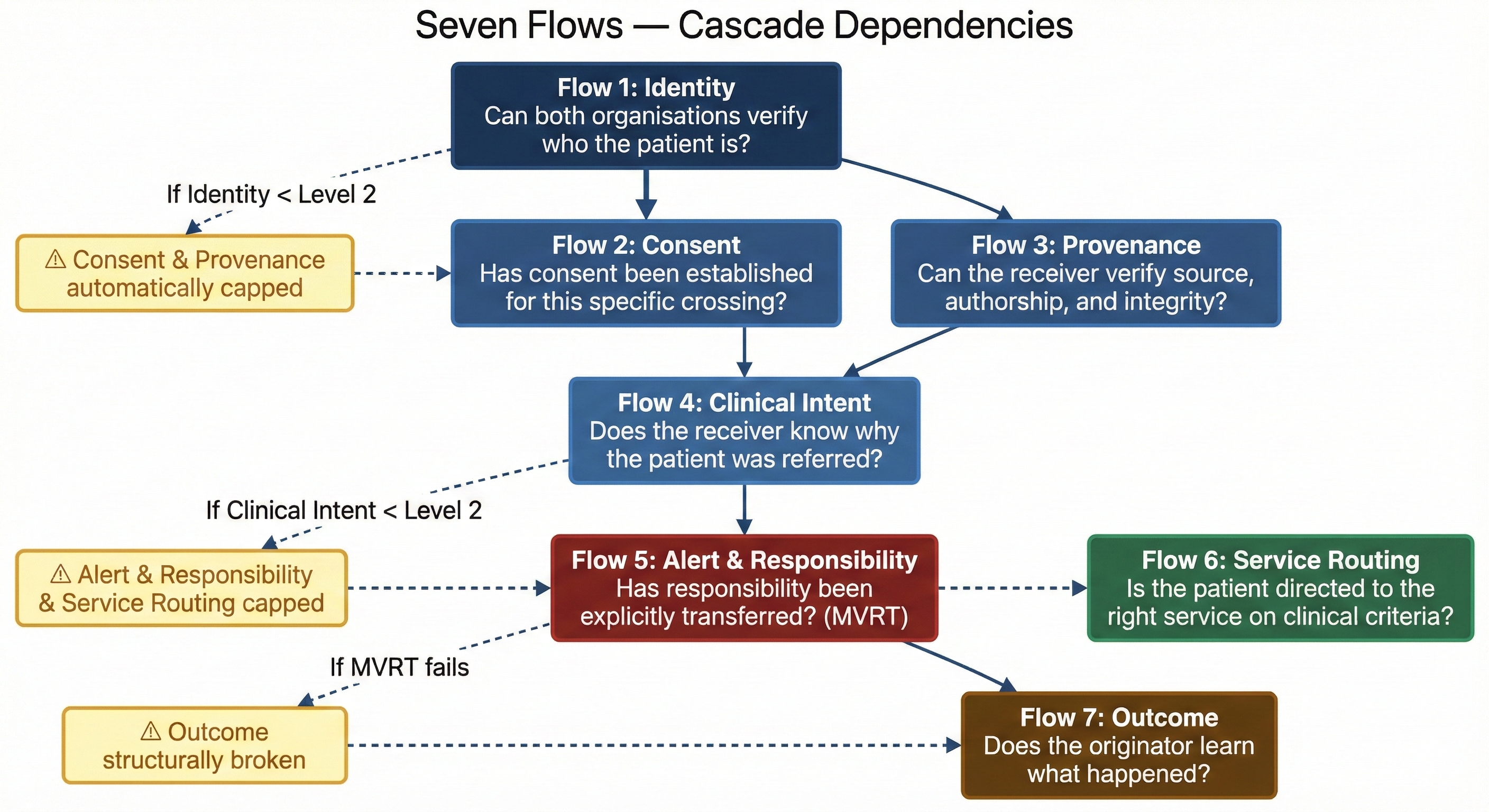

- The Seven Flows — Identity, Consent, Provenance, Clinical Intent, Alert & Responsibility, Service Routing, and Outcome — are what must function at every organisational crossing. Each derives from existing statutory obligations (CQC, UK GDPR, DCB 0129/0160).

- Cascading failure logic means flows are not independent: an upstream Identity failure caps Consent and Provenance; a Clinical Intent failure caps Alert & Responsibility and Service Routing; an MVRT failure structurally prevents the Outcome flow from functioning.

- Mapping must come before service design. The 43 NNHIP pioneer sites should assess Seven Flows at every boundary before integrated neighbourhood teams start operating across organisational lines.

The NHS England neighbourhood health guidelines for 2025/26 define six core components of neighbourhood health: population health management, modern general practice, standardising community services, neighbourhood multidisciplinary teams, integrated intermediate care, and urgent neighbourhood health services. These are the building blocks of the model. They describe what neighbourhood health should deliver.

They do not describe what must work at the joins between the organisations delivering it.

A 2025 systematic review published in BMC Public Health examined the integrated neighbourhood model across the literature and found that these models “lack a unified definition and standard framework for development and evaluation.” The review identified governance as a key enabler but framed it as organisational governance — leadership structures, shared vision, partnership working. The governance that functions at the operational boundary between two organisations, where a patient’s data crosses systems and clinical responsibility transfers between professionals employed by different bodies, was not addressed.

This is the gap that the Seven Flows framework is designed to fill. Before you design neighbourhood services, you need to map what must work at every boundary. Seven things must function. If any of them fails, patient safety is compromised — and the failure is invisible to every existing governance mechanism.

The physical space is not the governance space

The instinct in neighbourhood health planning is to start with services. What care will be delivered? By whom? In what building? Under what contract? These are important questions. But they are the wrong starting point if you are trying to build something that is safe as well as effective.

Every service design decision creates organisational boundaries. A neighbourhood MDT that brings together a GP, a community nurse, a mental health practitioner, and a pharmacist creates at least six bilateral boundaries between four organisations. Each boundary is a point where data crosses between systems, where clinical responsibility transfers between professionals, and where the governance frameworks of two independent organisations must connect.

The service design tells you what happens within each organisation. It does not tell you what happens between them. And at the boundary, seven things must function simultaneously.

The NHS Confederation’s analysis describes neighbourhood working as “both a mindset and method” and calls for “integrated health and care services and a workforce at the most local level.” This is correct. But integration without boundary governance is not integration. It is co-location with an assumption of safety. The mindset is right. The method — for what happens at the joins — does not yet exist in the national framework.

Our methodology provides it. We call it the Seven Flows.

The Seven Flows: what must function at every neighbourhood boundary

Each flow represents something that must work at every organisational crossing. They are not aspirational. They are structural requirements that derive from existing statutory obligations — CQC Regulation 12 (safe care), CQC Regulation 17 (good governance), UK GDPR Articles 5 and 6 (lawful processing), DCB 0129 and 0160 (clinical safety), and the duty of care that attaches to every clinician regardless of organisational context.

Flow 1: Identity at the shared reception

Can both organisations verify who the patient is at the point of data exchange?

This sounds trivially simple. In an NHS-to-NHS context, the NHS number provides a common identifier. But a neighbourhood health centre may include VCSE organisations that do not have NHS number access, community pharmacists using dispensing systems with their own patient identifiers, and digital platforms with independent identity verification. When the GP asks the mental health practitioner to see a patient, both systems need to confirm they are talking about the same person. When a voluntary sector social prescriber receives a referral, they need a verified identity to act on it safely.

Identity is the foundation. If it fails, nothing downstream can function reliably. In our framework, Identity has a structural relationship with every other flow — if it falls below a threshold level, it compromises the integrity of everything that follows.

Flow 2: Consent in the corridor

Has the patient’s consent been established for this specific boundary crossing — not just for internal processing within either organisation?

Consent in healthcare is layered and complex. Most organisations handle internal consent reasonably well — privacy notices, the National Data Opt-Out, lawful basis documentation under UK GDPR Article 6. But consent at a boundary is a different question. Has the patient been informed that their data is crossing from one organisation to another? If the crossing is between constitutional domains — say, from an NHS service to a commercially-operated pharmacy chain — has the patient been told that the institutional context of their data is changing?

In neighbourhood health centres, the informality of co-location makes this worse. The patient sees “the team.” They don’t necessarily understand that “the team” consists of four separate organisations with four separate data controller responsibilities. Consent that was adequate for internal processing may not be adequate for the boundary crossing that a multi-disciplinary conversation represents.

Flow 3: Provenance across the partition

Can the receiving organisation verify the source, authorship, and integrity of what it receives?

When a GP refers a patient to a hospital specialist, the referral arrives through a structured channel — e-RS, MESH — with identifiable authorship and a documented pathway. In a neighbourhood health centre, clinical information may cross boundaries through corridor conversations, shared screens, verbal handovers, or messages on coordination platforms. The provenance of that information — who said it, when, based on what clinical evidence — may not be captured.

Provenance matters because clinical decisions are made on received information. If a pharmacist reviews a medication based on information relayed verbally from the mental health practitioner, and that information is incomplete or misremembered, the pharmacist has no provenance trail to verify what they were told. The clinical decision is only as safe as the provenance of the information it is based on.

Flow 4: Clinical Intent in the MDT meeting

Does the receiving organisation know precisely why the patient was referred and what clinical action is expected?

Clinical Intent is the flow that distinguishes a governance-aware boundary from an informal handover. When the GP asks the community nurse to “take a look at Mrs Ahmed’s leg,” the clinical intent may seem obvious. But what specifically is the GP asking? A wound assessment? A dressing change? A clinical judgement about whether the wound requires secondary care referral? An ongoing monitoring plan?

In a formal referral system, clinical intent is (imperfectly) captured in the referral letter. In a co-located neighbourhood centre, clinical intent is often communicated verbally and assumed to be understood. The gap between what the referring clinician intended and what the receiving clinician understood is invisible until something goes wrong.

In our framework, Clinical Intent has a structural relationship with downstream flows. If the receiving organisation doesn’t fully understand why the patient was sent to them, they cannot make a safe judgement about accepting responsibility, routing the patient appropriately, or determining what constitutes a good outcome. A failure in Clinical Intent cascades.

Flow 5: Alert & Responsibility (MVRT) in the shared inbox

Is clinical responsibility explicitly transferred with bilateral confirmation?

This is the critical flow — the one whose failure has the most direct patient safety consequence. We have formalised the principle that underpins it as Minimum Viable Responsibility Transfer (MVRT): the requirement that responsibility transfer must be explicit, bilateral, and confirmed before it is complete. The sending organisation must release responsibility. The receiving organisation must accept it. Neither party can unilaterally declare the transfer complete.

In the first article in this series, we described how NHS England London’s targeted operating model calls for “protocols for shared care and handovers.” MVRT is what those protocols must achieve: infrastructure-enforced, bilateral responsibility transfer with clinically-timed escalation if acceptance doesn’t occur. Every other safety-critical industry — aviation, maritime, nuclear — solved this decades ago. Healthcare still permits clinical responsibility to transfer implicitly, with neither party formally confirming the handover.

In neighbourhood health centres, this is particularly acute because the volume of responsibility transfers is dramatically higher. Every multi-disciplinary interaction is a potential transfer. The corridor conversation model makes bilateral confirmation structurally impossible unless the infrastructure is specifically designed to enforce it. Our technology assessment examines how shared inboxes and clinical coordination platforms can either enforce or undermine bilateral confirmation at these boundaries.

Flow 6: Service Routing via the “warm handover”

Is the patient being directed to the right service based on clinical criteria and governance, not just availability or proximity?

Service Routing in a neighbourhood centre is deceptively complex. The patient is physically present in a building with multiple services. The instinct is to route based on proximity and availability — the mental health practitioner is free, so the GP asks them to see the patient. But clinically appropriate routing requires matching the patient’s needs to the right service, the right professional, and the right governance framework.

If a patient presents with a mental health concern that also involves a safeguarding dimension, routing to the mental health practitioner within the neighbourhood centre may not be sufficient — the case may require referral to the local authority’s safeguarding team, which operates under an entirely different statutory framework. Routing based on co-location rather than clinical criteria creates a risk that the patient receives a partial service that doesn’t address their full needs.

In our framework, Service Routing depends on the flows upstream. If Clinical Intent is poorly communicated, routing decisions are made on incomplete information. If Identity hasn’t been verified across systems, the receiving service may be unable to access relevant clinical history. Routing is only as good as the information it is based on.

Flow 7: Outcome capture in the fragmented record

Does the originating organisation learn what happened after the patient crossed the boundary?

This is the flow that closes the loop — and it is the one most likely to be entirely absent at neighbourhood boundaries. When the GP refers a patient to the mental health practitioner, does the GP learn the outcome? Not “was the patient seen” — that is a process metric — but “what was the clinical outcome of the intervention, and does it change anything about the GP’s ongoing management of this patient?”

Without Outcome flow, the GP has no feedback signal. They cannot know whether their referrals are appropriate, whether the boundary is functioning safely, or whether the same failures are recurring. The boundary becomes a one-way door. The patient goes through. The originating clinician never learns what happened on the other side.

The NHS England guidelines call for systems to “measure outcomes” and reference the Better Care Fund policy framework for outcome measurement. But these outcome measures operate at population and service level. They do not measure outcomes at the organisational boundary — did this specific patient, at this specific crossing, receive continuity of care, and did the originating clinician receive structured feedback? That is the Outcome flow, and it does not exist in the current framework.

Why the flows interact — and why this matters more than any individual flow

The Seven Flows are not independent dimensions to be assessed in isolation. They interact structurally. A failure in one flow cascades to compromise others, often in ways that are invisible until the entire picture is assembled.

Our methodology formalises these structural dependencies through cascading failure logic. The principle is straightforward: if an upstream flow fails, dependent downstream flows are capped — regardless of how well they appear to function in isolation.

Consider how this works in a neighbourhood centre.

Identity is the foundation. If two organisations cannot reliably confirm they are discussing the same patient, then Consent (was this patient’s consent verified?) and Provenance (is this information about the right patient?) are both structurally compromised. An Identity failure cascades downward.

Clinical Intent sits mid-chain. If the receiving organisation doesn’t understand why the patient was referred, then Alert & Responsibility (can they safely accept responsibility for something they don’t understand?) and Service Routing (can they route the patient appropriately without knowing the clinical purpose?) are both capped. A Clinical Intent failure limits what can be achieved downstream regardless of the quality of the receiving organisation’s internal processes.

Alert & Responsibility is the critical dependency for Outcome. If responsibility has not been explicitly transferred and accepted, there is no accountable party from whom outcome data can be expected. An MVRT failure structurally prevents the Outcome flow from functioning.

What is cascading failure logic?

In the Seven Flows framework, cascading failure logic means that when an upstream flow fails, dependent downstream flows are automatically capped — regardless of how well they appear to function in isolation. An Identity failure caps Consent and Provenance. A Clinical Intent failure caps Alert & Responsibility and Service Routing. An MVRT failure structurally prevents the Outcome flow. This produces boundary assessments that reveal structural risk invisible to any individual-flow analysis.

This cascading logic means that a neighbourhood boundary can look reasonably well-governed on individual dimensions while being structurally unsafe when the interactions are mapped. An organisation might see decent scores on Consent or Provenance, but when the cascade adjustments are applied, the picture changes — because upstream Identity or Clinical Intent failures undermine those apparently-acceptable scores. This is information that no existing governance framework produces, because no existing framework examines the flows together at the boundary.

Governance in the Integrated Neighbourhood Team (INT) Meeting

The INT meeting is where neighbourhood governance either works or doesn’t. When clinicians from four organisations sit around the same table to discuss a patient list, the Seven Flows determine whether that meeting produces governed care or unstructured information sharing. At minimum, the INT meeting must achieve:

- Verified identity — every patient discussed is confirmed across all systems present at the table, not just named verbally.

- Explicit consent scope — the sharing of patient information in a multi-organisational meeting is covered by an appropriate lawful basis, and patients are informed.

- Documented provenance — clinical information shared verbally is attributed to its source, and the INT record captures who said what.

- Stated clinical intent — when a task is assigned to another professional, the clinical purpose is explicit, not assumed from context.

- Bilateral responsibility transfer — when responsibility moves from one professional to another, both parties confirm the transfer. The INT chair ensures no patient leaves the meeting in a responsibility gap.

- Governance-based routing — referrals from the INT are directed based on clinical criteria, not corridor proximity.

- Structured outcome feedback — at the next INT meeting, outcomes from previous actions are reported back to the originating clinician.

Why mapping comes before design

The NNHIP’s four enabler groups — data/digital, finance, estates, and workforce — are all oriented towards building neighbourhood services. This is understandable. The political and operational imperative is to get services running. But building services before mapping the boundaries those services create is like building a house before surveying the land.

Mapping the Seven Flows at every organisational boundary within a neighbourhood reveals the governance infrastructure that needs to be in place before services go live. It answers questions that service design alone cannot:

Which organisational pairings within the neighbourhood have the weakest governance? If the GP-to-community-nurse boundary is reasonably well-governed (shared systems, established referral pathways) but the GP-to-VCSE boundary has no governance infrastructure at all (no shared identifier, no consent framework, no responsibility transfer protocol), then the VCSE partnership — which the neighbourhood health guidelines identify as a core component — is the boundary that needs governance investment before services scale.

Which flows are the systemic weaknesses? If Outcome flow scores zero across every boundary in the neighbourhood, that is a systemic issue that no amount of individual boundary improvement will fix. It requires a neighbourhood-wide governance mechanism for structured outcome reporting — a design decision that should be made before services launch, not retrofitted after.

Where do constitutional crossings create additional risk? If the neighbourhood includes a community pharmacy (commercial context), a VCSE organisation (variable governance framework), and a digital coordination platform (independent data controller), the boundaries between these and the NHS organisations carry constitutional complexity that same-sector boundaries do not. Our Constitutional Transition Matrix maps these crossings, identifies the enhanced governance requirements, and ensures they are addressed in the service design.

The private sector has the same mapping requirement

This mapping discipline applies identically outside the NHS. A private hospital group co-locating a GP practice, a diagnostic suite, and a specialist outpatient clinic in a single building faces the same seven questions at every internal boundary. A PE portfolio company integrating multiple healthcare providers faces the same cascading failure risks — and often with less standardised infrastructure than the NHS provides.

An insurer building an integrated care pathway across a network of approved providers has boundaries at every handover. The seven flows must function at each one. The insurer’s network contract governs the commercial relationship, but it almost certainly does not specify how Identity is propagated across providers, how Clinical Intent is communicated at each referral, how responsibility is transferred bilaterally, or how the originating provider learns the outcome of the downstream care.

The mapping discipline is the same regardless of sector. Map the boundaries. Map the flows at each boundary. Identify the cascading dependencies. Then design the services — and the governance infrastructure to support them.

A checklist for the Integrated Neighbourhood Team (INT)

Our Seven Flows methodology produces a structured map of every organisational boundary within a neighbourhood or healthcare network. For each boundary, it identifies which of the seven flows function, which are absent, and where cascading failure logic means that an apparently-adequate flow is structurally compromised by an upstream failure.

What it does not do is replace any existing governance framework. CQC’s fundamental standards, DCB 0129 and 0160, UK GDPR, PSIRF — these remain the statutory instruments. The Seven Flows methodology sits in the gap between them: the space at the organisational boundary where each framework’s coverage ends and no existing assessment mechanism operates.

For the 43 NNHIP pioneer sites, the implication is specific. Before neighbourhood services scale, the boundaries should be mapped. Before integrated neighbourhood teams start operating across organisational lines, the seven flows should be assessed at each crossing. Before the corridor conversations begin, the infrastructure for governed handovers should exist.

The service design is the visible part of neighbourhood health. The boundary governance is the foundation. You do not see it when it works. You see it — in a serious incident report, in a coroner’s inquest, in a regulatory investigation — when it fails.

The next article in the Architecting for Neighbourhood Health series examines the fifth and most critical flow — Alert & Responsibility — and the principle of Minimum Viable Responsibility Transfer. In neighbourhood health centres, where clinical responsibility shifts constantly between co-located organisations, MVRT is the difference between governed care and an assumption of safety.

Architecting Neighbourhood Health Series

- Architecting for Neighbourhood Health: What the Implementation Programme Is Missing

- Mapping the Seven Flows in a Neighbourhood Health Centre (current)

- Clinical Responsibility Transfer — Why Handover Frameworks Don’t Cross Organisational Boundaries

- Constitutional Complexity — Five Organisations, Five Legal Frameworks, One Building

- Boundary Readiness — Why “People, Process, Technology” Fails at Healthcare Boundaries

- The Legal Pillar — Data Sharing, Contractual Frameworks, and Constitutional Compliance

- The Clinical Safety Pillar — When the Hazard Sits Between Organisations

- The Process Pillar — Crossing Choreography and the Pre-Conditions Nobody Defines

- The People Pillar — Why Generic MDT Training Doesn’t Cross Organisational Boundaries

- The Technology Pillar — Why Interoperability That Doesn’t Preserve Governance Is Interoperability in Name Only

Inference Clinical’s Seven Flows Boundary Governance Audit maps and assesses governance at every organisational boundary. Per-boundary scorecards with cascading failure logic, constitutional transition analysis, and MVRT compliance assessment. To understand how your neighbourhood boundaries would score, book a scoping call.