Key Takeaways

- Referral pathways define clinical triggers but not governance choreography — pathway says when and where to refer but not what must be confirmed at the boundary before a crossing is valid

- Each bilateral boundary supports multiple crossing types — routine referral, urgent/crisis, advice & guidance, feedback, informal corridor consultation — each with different pre-conditions

- Pre-conditions have three categories — sender (what originating org must confirm), receiver (what receiving org must confirm including MVRT bilateral confirmation), bilateral (shared understanding of urgency, escalation, feedback)

- Co-location makes process harder, not easier — physical proximity reduces formality, which reduces pre-condition verification. Informal crossings are the most frequent and least governed.

- Process depends on Legal and Clinical Safety pillars — sender pre-conditions depend on data controller mapping (Legal), receiver pre-conditions depend on hazard severity assessment (Clinical Safety), bilateral pre-conditions depend on contractual frameworks

This is the eighth article in the Architecting for Neighbourhood Health series. The first article examined why the current governance conversation addresses committee structures but not boundary governance. The second introduced the Seven Flows. The third went deep on clinical responsibility transfer and the MVRT principle. The fourth examined constitutional complexity. The fifth introduced the Boundary Readiness model. The sixth examined the Legal pillar. The seventh examined the Clinical Safety pillar. This article examines the third pillar: Process — the translation layer where legal permissions and clinical safety requirements become operational reality.

The Legal pillar asks may this crossing happen. The Clinical Safety pillar asks what goes wrong when it fails. The Process pillar asks a question that sounds simple but is almost never answered: what must each party confirm before this specific crossing can validly occur?

Not what must be true in general. Not what good practice looks like in the abstract. What specific pre-conditions must be satisfied — and confirmed by both sides — before this type of crossing, between these two organisations, for this clinical purpose, can proceed. A GP referring a patient to a co-located cardiologist has different pre-conditions from a GP referring to the co-located mental health practitioner. A hospital discharging a patient to GP care has different pre-conditions from a community nurse transferring ongoing care to a VCSE social prescriber. A pharmacist escalating a Pharmacy First consultation to the GP has different pre-conditions from a GP referring to the pharmacist for a medication review.

Each crossing type has its own choreography. The Process pillar is where that choreography gets defined — or, in most neighbourhood health configurations, where it doesn’t.

Why “referral pathway” is not enough

The NHS has invested significantly in referral infrastructure. The e-Referral Service provides electronic referral from primary to secondary care, with advice and guidance functionality that allows GPs to seek specialist input before committing to a formal referral. Local referral pathways define which clinical criteria should trigger a referral to which service. NICE guidelines provide condition-specific referral thresholds. Commissioning policies define which procedures require prior approval.

These are valuable mechanisms. They are also incomplete in a critical respect: they define when and where to refer, but not what must be true at the boundary before the referral can be safely accepted. Integrated Care Pathway design focuses on the clinical journey; it does not address the governance choreography at each organisational boundary the pathway crosses. Similarly, a Service Level Agreement (SLA) for referrals defines performance expectations — response times, acceptance rates — but not the bilateral pre-conditions that make each crossing governmentally valid. An inter-agency referral protocol may specify information requirements, but rarely defines the sender, receiver, and bilateral pre-conditions that the Process pillar requires.

A referral pathway says: “If the patient presents with these symptoms and these investigation results, refer to Cardiology.” It does not say: “Before Cardiology can accept this referral, the following must be confirmed: the patient’s identity has been verified against PDS by both organisations, the patient understands their information is being shared with a separate data controller, the referral includes the specific investigation results the cardiologist requires to triage, the GP has documented their clinical intent in a structured format the receiving system can parse, and responsibility for the patient during the referral-to-appointment interval has been explicitly assigned.”

The pathway defines the clinical trigger. The Process pillar defines the governance choreography — the sequence of confirmations that must occur before the boundary crossing is valid. Without the choreography, the referral may be clinically appropriate but governmentally incomplete. And governmentally incomplete crossings are where boundary incidents originate.

Crossing types: not all boundaries are the same

The fifth article in this series established that a neighbourhood health centre with five organisations has ten bilateral boundaries. The Process pillar adds a further dimension: each bilateral boundary supports multiple crossing types, and each crossing type has different pre-conditions.

Consider a single boundary — the one between the GP practice and the community mental health Trust. At this boundary, at least five distinct crossing types occur regularly.

Routine referral — the GP identifies a patient who needs mental health assessment and generates a referral. The pre-conditions include: sufficient clinical history for triage, documented clinical intent (assessment? treatment? crisis intervention?), confirmed patient understanding of the referral destination, and a defined responsibility model for the interval between referral and first contact.

Urgent or crisis referral — the GP encounters a patient in acute mental health crisis. The pre-conditions shift: triage information must be minimal but specific (risk to self, risk to others, current location), the timeline for acceptance compresses from days to hours, and responsibility transfer must be immediate and confirmed rather than deferred. The choreography is fundamentally different from a routine referral, yet both cross the same bilateral boundary.

Advice and guidance — the GP wants specialist input without a formal referral. The pre-conditions here include what clinical information must be shared (which may differ from a full referral), whether the patient is aware their case is being discussed, and — critically — who retains responsibility for the patient if the specialist’s advice changes the clinical plan. Advice and guidance crosses a boundary without transferring responsibility, which makes it governmentally distinct from a referral.

Feedback or outcome communication — the mental health practitioner communicates back to the GP about what happened. The pre-conditions include: what information the GP needs to update the care plan, what format allows the GP system to process it, whether the communication constitutes a discharge (responsibility transfer back to GP) or an interim update (shared responsibility continues), and the timeframe within which the GP can reasonably expect it.

Informal corridor consultation — the GP walks to the next room and discusses a patient with the mental health practitioner. This is the crossing the fifth diagram in this series illustrated — what it feels like (teamwork) versus what it actually is (seven governance questions, all unanswered). The pre-conditions are the same as for any other crossing, but the informality of the interaction means none of them are addressed. No identity verification. No documented consent. No provenance trail. No explicit clinical intent. No responsibility transfer. No service routing logic. No outcome expectation. This is why the Process pillar must explicitly address informal crossings — because they are the most frequent and the least governed.

That is five crossing types at a single bilateral boundary. Multiply by ten boundaries, and a neighbourhood health centre could have fifty or more distinct crossing types, each with its own pre-conditions, its own choreography, and its own failure modes.

The pre-condition framework

What Are Clinical Boundary Pre-Conditions?

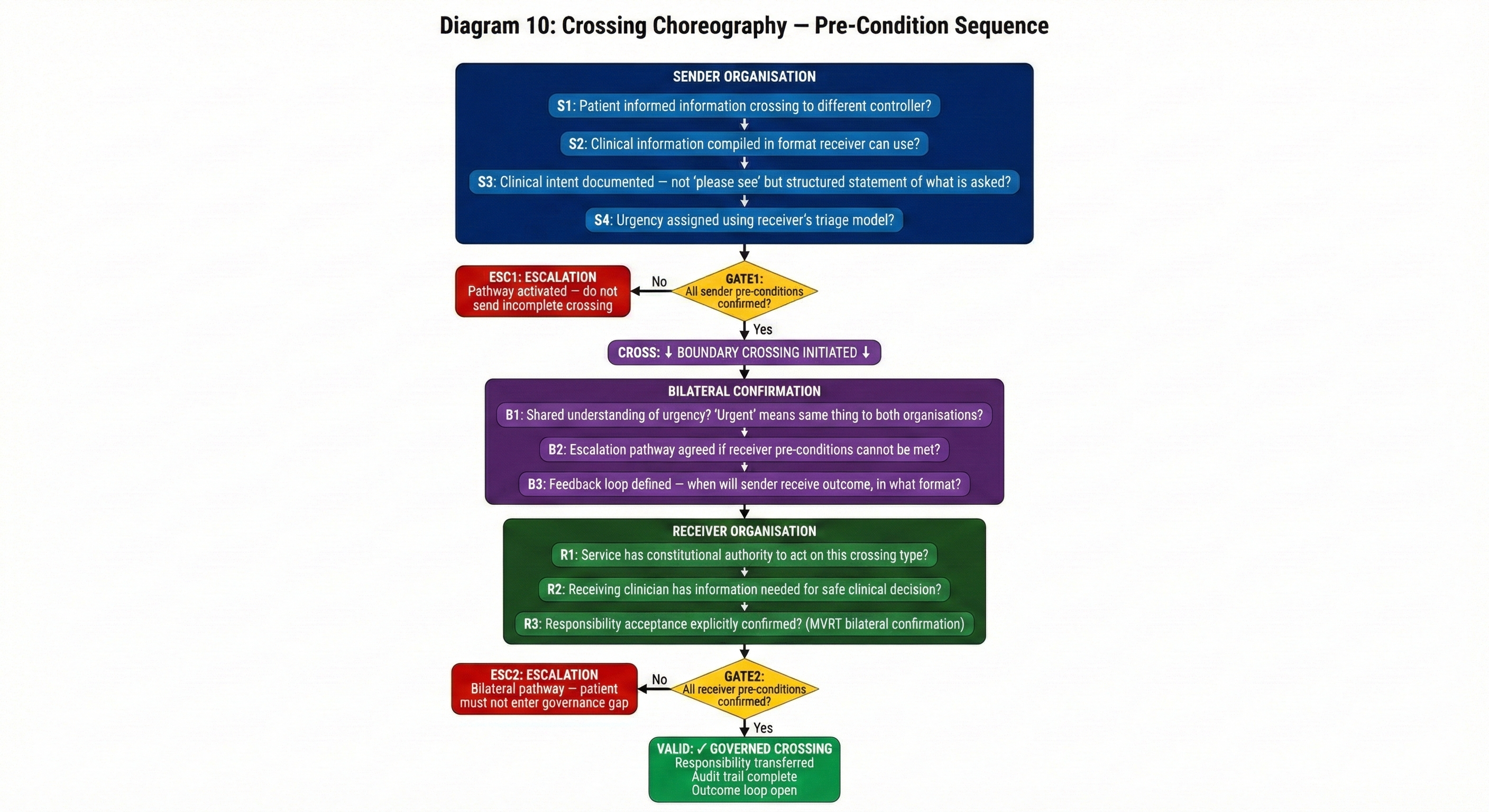

Clinical boundary pre-conditions are specific criteria that must be confirmed by both the sending and receiving organisation before a patient’s care can validly cross an organisational boundary. They fall into three categories: sender pre-conditions (what the originating organisation must confirm), receiver pre-conditions (what the receiving organisation must confirm, including MVRT bilateral confirmation of responsibility transfer), and bilateral pre-conditions (shared understanding of urgency, escalation pathways, and feedback expectations). Pre-conditions are defined per crossing type and mapped to the Seven Flows governance framework.

For each crossing type, the Process pillar defines pre-conditions across three categories.

Sender pre-conditions are what the originating organisation must confirm before initiating the crossing. Has the patient been informed that their information will be shared with a different organisation? Has the clinical information been compiled in a format the receiving organisation can use? Has the clinical intent been documented — not just “please see” but a structured statement of what the GP is asking for and what they expect to happen? Has the appropriate urgency been assigned, and does the sending clinician understand what urgency means in the receiving organisation’s triage model?

Sender pre-conditions sound obvious when stated explicitly. In practice, they are the most commonly violated category. Patient Safety Learning has documented the growing problem of referral rejections — where specialist services return referrals to GPs because pre-conditions have not been met. The clinical information is insufficient for triage. The required investigations have not been completed. The referral criteria have not been satisfied. Each rejection represents a crossing that was initiated without its sender pre-conditions being confirmed. Each rejection creates delay, clinical risk, and duplicated work.

Receiver pre-conditions are what the receiving organisation must confirm before accepting the crossing. Does the service have the constitutional authority to act on this referral (the Clinical Intent problem from Article 4 — the mental health Trust’s service specification may limit what the co-located practitioner can do)? Does the receiving clinician have the information needed to make a safe clinical decision? Has the receiving organisation confirmed acceptance of responsibility — or is the referral sitting in a queue that nobody has acknowledged?

Receiver pre-conditions are where MVRT — the Minimum Viable Responsibility Transfer from the third article — operationalises. The receiver pre-condition for any crossing that involves responsibility transfer is bilateral confirmation: the receiving organisation must explicitly confirm that it has received the referral, that it accepts responsibility for the patient from the defined point in time, and that the information provided is sufficient for safe care. Without this confirmation, the crossing is incomplete and the patient is in the governance gap.

Bilateral pre-conditions are requirements that must be confirmed by both organisations together. These include: the shared understanding of urgency (does “urgent” mean the same thing to the sender and the receiver?), the agreed escalation pathway if pre-conditions cannot be met (what happens when the cardiologist needs an echocardiogram the GP hasn’t arranged?), and the defined feedback loop (when will the sender receive outcome communication, and what will it contain?).

Bilateral pre-conditions are the hardest category to define because they require agreement between organisations that may have different clinical cultures, different risk appetites, and different operational pressures. A GP practice under pressure to reduce referral rates has a different relationship to sender pre-conditions than a GP practice with adequate capacity. A specialist service with a six-month waiting list has a different relationship to receiver pre-conditions than one with capacity available. The bilateral pre-conditions must be negotiated, documented, and maintained despite these asymmetries.

Why co-location makes process harder, not easier

One of the assumptions behind neighbourhood health centres is that co-location makes cross-organisational working easier. And at the human level, it does. Relationships form. Trust develops. Informal consultation becomes natural. Clinicians learn each other’s capabilities and preferences. The corridor conversation replaces the formal referral.

The Process pillar reveals why this apparent ease is a governance risk. Every reduction in formality is a reduction in pre-condition verification. The corridor conversation skips sender pre-conditions (the patient hasn’t been told, the clinical intent isn’t documented, the information isn’t structured). It skips receiver pre-conditions (the mental health practitioner hasn’t confirmed acceptance of responsibility, hasn’t verified they have the information needed for safe decision-making). It skips bilateral pre-conditions (there is no agreed urgency, no defined escalation, no expected feedback loop).

Co-location does not eliminate the governance requirements at a boundary. It makes them invisible. The boundary still exists — the organisations are still constitutionally distinct, still separate data controllers, still subject to different regulatory frameworks. But the physical proximity creates an experience of unity that masks the governance reality of separation. The Process pillar must therefore define not just the choreography for formal crossings but explicit expectations for the governance of informal interactions that co-location encourages.

This does not mean banning corridor conversations. It means defining the minimum governance that even an informal crossing must satisfy. If a GP discusses a patient with a co-located mental health practitioner, both must at minimum document the interaction, confirm the patient’s awareness, and agree whether clinical responsibility has shifted. These are not bureaucratic hurdles. They are the minimum conditions under which the interaction is governmentally valid and clinically auditable.

Crossing choreography in practice

Defining crossing choreography for every crossing type at every boundary sounds overwhelming. In practice, it follows a structured methodology.

First, enumerate the crossing types at each bilateral boundary. Not every pair of organisations shares every type of crossing. The GP practice and the community pharmacy have different crossing types from the GP practice and the community Trust. Referral, advice and guidance, escalation, feedback, discharge, and informal consultation are common categories, but the specific crossings within each category depend on the services delivered at the boundary.

Second, for each crossing type, define the pre-conditions in all three categories — sender, receiver, and bilateral. This is a clinical governance exercise, not an administrative one. The pre-conditions for a GP-to-mental-health-crisis referral must be defined by clinicians from both organisations working together, because only they understand what the receiving service needs to act safely and what the sending practice can reasonably provide.

Third, map the pre-conditions to the Seven Flows. Each pre-condition corresponds to one or more of the seven governance dimensions. “The patient must be informed that their information is being shared with a different data controller” is a Consent pre-condition. “The referral must include the specific investigations the cardiologist requires” is a Provenance and Clinical Intent pre-condition. “The receiving organisation must confirm acceptance of responsibility” is an Alert & Responsibility (MVRT) pre-condition. This mapping connects the Process pillar to the Clinical Safety pillar — because a pre-condition that is not met corresponds to a hazard that has been identified but not controlled.

Fourth, define the escalation pathway for each crossing type when pre-conditions cannot be met. What happens when the GP initiates a referral but the sender pre-conditions are not satisfied — the investigations haven’t been done, the clinical information is incomplete? What happens when the receiving organisation identifies that the referral doesn’t meet receiver pre-conditions — the clinical intent is unclear, the urgency assessment is inappropriate for the service specification? The escalation pathway must be pre-defined, bilateral, and clinically safe. “Reject and return” is not a clinically safe escalation for an urgent referral where the patient needs specialist input regardless of whether the referral paperwork is complete.

Fifth, document the choreography in a format that is usable by the clinicians who work at the boundary. This is not a policy document that sits in a governance folder. It is an operational reference that tells a GP: “Before referring to the co-located mental health service, confirm these five things. When referring urgently, confirm these three instead. If you cannot confirm them, use this escalation pathway.” If the choreography cannot be summarised in a form that a clinician can use in the time available, it will not be used — and the crossings will revert to informal, ungoverned interactions.

Checklist for a Cross-Boundary SOP

A cross-boundary Standard Operating Procedure must cover the following at minimum for each crossing type:

- Sender Pre-conditions — patient informed of cross-organisational sharing, clinical information compiled in receiver-compatible format, clinical intent documented in structured form, urgency assigned using shared triage criteria

- Receiver Pre-conditions — constitutional authority to act confirmed, information sufficiency verified, MVRT bilateral confirmation of responsibility acceptance with defined start point

- Bilateral Pre-conditions — shared definition of urgency levels, agreed escalation pathway when pre-conditions cannot be met, defined feedback loop (content, format, and timeframe)

- Escalation Pathway — pre-defined route for each crossing type when sender or receiver pre-conditions fail, ensuring no patient is left without a responsible clinician

- Informal Crossing Minimum — documentation requirement, patient awareness confirmation, explicit agreement on whether responsibility has shifted

- Seven Flows Mapping — each pre-condition mapped to the relevant governance flow(s), cross-referenced to the boundary hazard log

- Audit Trail — how the crossing and its pre-condition confirmations are recorded for clinical safety monitoring and regulatory compliance

Process depends on Legal and Clinical Safety

The Boundary Readiness model places Process as the third pillar, after Legal and Clinical Safety. This dependency is operational, not just conceptual.

The sender pre-condition “the patient must be informed that their information is being shared with a separate data controller” can only be defined once the Legal pillar has established the data controller status of each organisation. If the Legal pillar assessment determines that two co-located organisations are joint controllers for a specific activity, this pre-condition changes — the patient does not need to be separately informed because the processing occurs under a joint controllership arrangement.

The receiver pre-condition “the referral must include the specific investigations the cardiologist requires” can only be defined once the Clinical Safety pillar has identified the hazard of “referral arrives without required clinical information” and assessed its severity. If the Clinical Safety assessment determines that this hazard is high-severity, the pre-condition must be mandatory — the system should prevent the referral from being sent without the required information attached. If the hazard is lower severity, the pre-condition may be advisory rather than blocking.

The bilateral pre-condition “both organisations agree an escalation pathway for urgent referrals where pre-conditions cannot be met” depends on the Legal pillar having established the contractual framework (what each organisation is obligated to provide) and the Clinical Safety pillar having assessed the hazard of delayed escalation (what happens to the patient if the escalation pathway fails). The Process pillar operationalises the requirements that Legal and Clinical Safety define.

Without the Legal and Clinical Safety pillars in place, the Process pillar is guesswork. Pre-conditions are defined based on clinical intuition rather than legal architecture. Escalation pathways are defined without reference to the hazard analysis. And the choreography, however well-intentioned, may require actions that the legal framework does not support or omit actions that the clinical safety assessment identifies as essential.

What the Process pillar assessment requires

At Inference Clinical, the Process pillar assessment covers four domains at every bilateral boundary.

First, crossing type enumeration — a complete mapping of the distinct crossing types that occur at the boundary, including formal referrals, informal consultations, advice and guidance, escalations, discharges, and feedback communications. This is developed bilaterally — both organisations participate, because crossing types are defined by the interaction, not by either organisation in isolation.

Second, pre-condition definition — for each crossing type, documented sender pre-conditions, receiver pre-conditions, and bilateral pre-conditions, mapped to the Seven Flows and cross-referenced to the Clinical Safety pillar’s boundary hazard log. Where a pre-condition corresponds to a hazard control, the Process pillar verifies that the pre-condition is sufficient to mitigate the identified hazard.

Third, escalation pathway definition — for each crossing type, a defined and bilateral escalation pathway for scenarios where pre-conditions cannot be met. The escalation pathway must be clinically safe (it cannot create a situation where the patient has no responsible clinician), operationally realistic (it must account for the capacity and response times of both organisations), and auditable (the escalation must generate a record that feeds back into the Clinical Safety pillar’s monitoring).

Fourth, informal crossing governance — specific expectations for the minimum governance of informal boundary crossings that co-location encourages. This includes defining which interactions constitute a crossing (not every conversation about a patient crosses a governance boundary — clinical small talk is different from clinical decision-making), what documentation is required for interactions that do constitute a crossing, and how informal crossings feed into the formal audit trail that the Clinical Safety pillar requires.

The private sector translation

In private healthcare, crossing choreography is shaped by commercial as well as clinical logic. An insurer’s pre-authorisation process is, structurally, a sender pre-condition — it must be satisfied before the referral to a specialist can validly proceed. But pre-authorisation is defined by commercial criteria (is this treatment covered by the policy?) as well as clinical criteria (is this treatment clinically appropriate?). The choreography must satisfy both.

Provider-to-provider crossings in private healthcare have the same Process requirements as NHS boundaries: sender pre-conditions, receiver pre-conditions, bilateral pre-conditions, escalation pathways. The challenge is that private healthcare has fewer standardised crossing types and fewer mandated pathways. Each insurer has its own pre-authorisation process. Each provider network has its own referral expectations. The Process pillar in private healthcare must often be built from first principles rather than adapted from existing NHS infrastructure.

The principle, again, is constant: wherever patient care crosses an organisational boundary, the crossing has pre-conditions. Those pre-conditions are specific to the crossing type. They must be defined bilaterally. And they must be met before the crossing is governmentally valid — regardless of whether the setting is an NHS neighbourhood health centre or a private insurer’s provider network.

The operational gap

Neighbourhood health centres are being designed around estates, digital infrastructure, and workforce models. The operational question of what must be true at each crossing, for each crossing type, at each boundary, before the first patient interaction — that question is not being systematically addressed. The four enabler groups in the NNHIP (data/digital, finance, estates, workforce) do not include a process choreography workstream. The referral pathway infrastructure defines when to refer and where to refer, but not the bilateral pre-conditions that make the crossing governmentally valid.

This is the gap the Process pillar fills. It is the translation layer between what Legal permits and what Clinical Safety requires, on one hand, and what clinicians actually do at the boundary, on the other. Without it, the legal architecture is theoretical, the hazard analysis is academic, and the crossings that happen in practice — especially the informal ones that co-location makes so easy — are ungoverned.

Process is not the most visible pillar. It is the most operational. It is the pillar that determines whether the governance architecture works where it matters — in the ten seconds between a GP deciding a patient needs a co-located specialist and the GP picking up the phone or walking to the next room.

The next article examines the People pillar: why generic MDT training is insufficient, what boundary-specific competence looks like, and how the humans who work at organisational crossings must understand the specific governance architecture of their specific boundaries.

Architecting Neighbourhood Health Series

- What the Implementation Programme Is Missing

- Mapping the Seven Flows in a Neighbourhood Health Centre

- Clinical Responsibility Transfer — Why Handover Frameworks Don’t Cross Organisational Boundaries

- Constitutional Complexity — Five Organisations, Five Legal Frameworks, One Building

- Boundary Readiness — Why “People, Process, Technology” Fails at Healthcare Boundaries

- The Legal Pillar — Data Sharing, Contractual Frameworks, and Constitutional Compliance

- The Clinical Safety Pillar — When the Hazard Sits Between Organisations

- The Process Pillar — Crossing Choreography and the Pre-Conditions Nobody Defines (current)

- The People Pillar — Why Generic MDT Training Doesn’t Cross Organisational Boundaries

- The Technology Pillar — Why Interoperability That Doesn’t Preserve Governance Is Interoperability in Name Only

Inference Clinical’s Seven Flows Boundary Governance Audit assesses the Process pillar at every bilateral boundary — crossing type enumeration, pre-condition mapping across all seven flows, escalation pathway definition, and informal crossing governance. To define the crossing choreography for your neighbourhood boundaries, book a scoping call.