Key Takeaways

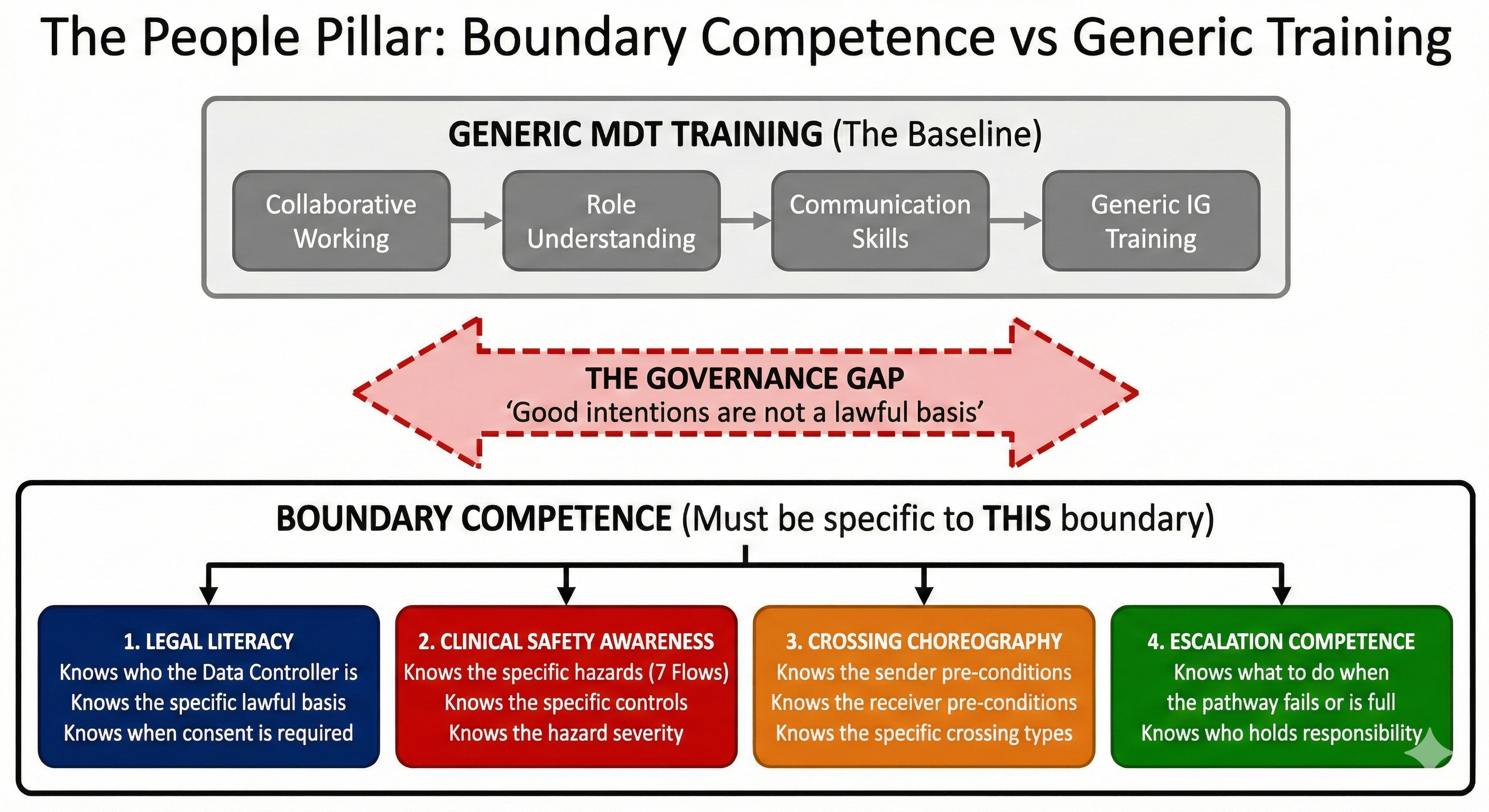

- Generic MDT training teaches collaborative working but not boundary governance — clinicians aren’t told which organisation is the data controller, what the pre-conditions are, or who holds responsibility during referral intervals

- Boundary competence has four components — legal literacy at the boundary, clinical safety awareness, crossing choreography knowledge, and escalation competence

- Boundary competence must be boundary-specific — the governance architecture at the GP-to-Trust boundary differs from GP-to-VCSE; generic “working across boundaries” training is insufficient

- Different professional regulators (GMC, NMC, HCPC, GPhC) define different handover and delegation standards — regulatory frameworks intersect at boundaries but were defined independently

- The People pillar depends on Legal, Clinical Safety, and Process — without the preceding three pillars, there is nothing specific to teach, only generic principles that dissolve on contact with reality

This is the ninth article in the Architecting for Neighbourhood Health series. The first article examined why the current governance conversation addresses committee structures but not boundary governance. The second introduced the Seven Flows. The third went deep on clinical responsibility transfer and the MVRT principle. The fourth examined constitutional complexity. The fifth introduced the Boundary Readiness model. The sixth examined the Legal pillar. The seventh examined the Clinical Safety pillar. The eighth examined the Process pillar. This article examines the fourth pillar: People — why generic MDT training is insufficient and what boundary-specific competence actually requires.

The first three pillars of the Boundary Readiness model define architecture. Legal establishes what is permitted. Clinical Safety identifies what fails. Process defines the choreography for each crossing type. The fourth pillar asks whether the people who work at boundaries understand any of this.

The answer, in most neighbourhood health configurations, is that they do not — because nobody has told them. Clinicians are trained in clinical practice. They are trained in their own organisation’s policies and procedures. They are trained in generic multi-disciplinary team working. What they are not trained in is the specific governance architecture of the specific boundaries at which they work: which organisation is the data controller for this interaction, what the pre-conditions are for this crossing type, who holds clinical responsibility during the referral-to-appointment interval, and what they should do when the governance architecture fails to support the clinical decision they need to make.

This is not a training gap that generic MDT development can fill. It is a boundary-specific competence requirement — and it is the People pillar’s job to define it.

The MDT training assumption

The Neighbourhood Health Guidelines for 2025/26 emphasise multi-disciplinary team working as a core component of neighbourhood health. The guidelines propose integrated neighbourhood teams providing proactive, planned, and responsive care, with a core team managing complex cases and linking to extended specialist resources. Skills development for team members is identified as a priority. NHS England’s MDT Toolkit provides a framework for developing a “one workforce” approach across health and care organisations.

These are valuable investments. They also contain an assumption that the series has been systematically challenging: that bringing people together, whether physically or organisationally, reduces the governance complexity of their interactions. MDT training teaches clinicians to work collaboratively, to understand each other’s roles, to communicate effectively, to share information appropriately. All essential competencies. All designed for team working within a shared governance framework. An NHS workforce integration strategy that focuses on cross-organisational team development without addressing boundary governance is solving the interpersonal problem while ignoring the structural one.

In a neighbourhood health centre, the Integrated Neighbourhood Team (INT) spans multiple independent organisations, multiple regulatory frameworks, multiple data controllers, multiple clinical safety architectures, and multiple contractual obligations. The MDT training teaches the clinical and interpersonal competencies. It does not teach the governance competencies that working across organisational boundaries demands. An INT workforce plan that omits boundary governance competence is a workforce plan for a team that does not legally exist as a single entity.

A community nurse trained in MDT working knows how to contribute to a multi-disciplinary case discussion. She may not know that the case discussion crosses a data controller boundary between her Trust and the GP practice, that the information she shares requires a lawful basis under UK GDPR, that her Trust’s Caldicott Guardian and the practice’s Caldicott Guardian have agreed a specific protocol for this type of sharing, or that if she shares safeguarding concerns with the co-located VCSE link worker, she is crossing from a high-assurance DSPT environment to one that may have no formal data security assessment at all.

She doesn’t know these things because nobody has told her. Her Trust’s induction covers Trust policies. The MDT training covers collaborative working. Neither covers the specific governance reality of the specific boundaries at which she works every day.

What boundary competence actually means

What Is Boundary Competence?

Boundary competence is the specific ability of a staff member to identify, navigate, and govern the legal, safety, and process requirements at the organisational boundaries they work across. Unlike generic governance awareness, boundary competence is developed per boundary and derived from the Legal, Clinical Safety, and Process pillar assessments for that specific boundary.

Boundary competence is not a generic skill. It is knowledge of the specific governance architecture at a specific boundary, applied to the specific crossing types that occur there. It has four components.

Legal literacy at the boundary means the clinician understands, at a practical level, the legal architecture governing data sharing at their specific crossings. Not the full detail of UK GDPR Article 6 and Article 9 — that is the Legal pillar’s domain. But the practical implications: which organisations in this building are separate data controllers, what that means for the information they can and cannot share, when they need the patient’s explicit understanding that information is crossing to a different organisation, and what they should do when they are unsure whether a specific sharing decision is lawful.

This is not currently part of any standard induction programme. Information governance training — mandatory for all NHS staff — covers general principles of data protection. It does not cover the specific data controller architecture of the specific neighbourhood health centre where the clinician works. It does not explain that the GP practice next door is an independent data controller with its own IG framework. It teaches clinicians that they must protect patient data. It does not teach them the specific rules governing what happens when they share patient data across the boundary three metres from their desk.

Clinical safety awareness at the boundary means the clinician understands the specific hazards that have been identified at their specific crossings, and the controls that exist to mitigate them. The seventh article identified seven categories of boundary hazard — identity, consent, provenance, clinical intent, alert and responsibility, service routing, and outcome. Boundary competence means the clinician knows which of these hazards are most significant at their particular boundary, what the consequences of a hazard materialising would be for the patient, and what they are personally required to do to prevent it.

A GP who refers to the co-located mental health service should know that the most significant boundary hazard is the Clinical Intent gap — the mismatch between what the GP expects (full assessment) and what the Trust’s service specification permits the practitioner to do (triage only). Knowing this changes behaviour. The GP documents clinical intent explicitly, confirms with the receiving service that their expectation is achievable, and has a defined escalation pathway when it is not. Without boundary-specific safety awareness, the GP writes “please see” on the referral and assumes the rest will work itself out. It usually does. When it doesn’t, the patient falls through the gap.

Crossing choreography knowledge means the clinician knows the pre-conditions for the specific crossing types they initiate or receive, as defined by the Process pillar. What must they confirm before sending a referral? What must they verify before accepting one? What constitutes a valid escalation? What minimum governance must even an informal corridor conversation satisfy?

This is the most operational component of boundary competence and the one most likely to change behaviour. A clinician who knows that the pre-conditions for referring to the co-located community pharmacy include confirming the patient’s understanding that the pharmacist is a separate data controller, attaching the current medication list, and documenting the clinical intent of the referral, will produce a qualitatively different referral from a clinician who knows only that “the pharmacist is next door.” The choreography transforms the crossing from an informal interaction into a governed one. But it only transforms behaviour if the people at the boundary know the choreography exists.

Escalation competence means the clinician knows what to do when the governance architecture does not support the clinical decision they need to make. This is the component most often missing — and the one that matters most in the moments when boundary governance is under stress.

A GP encounters a patient in acute crisis. The mental health service next door has no capacity. The pre-conditions for an urgent referral cannot be met because the service’s triage pathway is full. What does the GP do? Without escalation competence, the GP either holds the risk (keeping the patient without the specialist input they need) or bypasses the governance architecture entirely (walking to the mental health practitioner’s room and asking them to see the patient informally, creating a crossing with no documented consent, no recorded clinical intent, no defined responsibility transfer).

Escalation competence means the GP knows that an alternative pathway exists, who to contact, what information to provide, and what the governance framework says about responsibility during the escalation interval. It means the GP has been told — specifically, for this boundary, for this crossing type — what to do when the normal pathway fails. Good Medical Practice 2024 requires doctors to check that a named clinician or team has taken over responsibility when their role in a patient’s care has ended. Escalation competence is what makes that requirement achievable at an organisational boundary where the named clinician works for a different organisation with different systems, different capacity, and different governance.

A Boundary Competence Framework for Neighbourhood Teams

Training must be based on the specific legal and process architectures defined in earlier pillars. The boundary competence framework for each bilateral boundary covers:

- Legal Basis Awareness — which organisation is the data controller for each crossing type, what lawful basis applies, when explicit patient understanding is required, and what the Caldicott coordination arrangements are at this boundary

- Boundary Hazard Knowledge — the specific hazards identified at this boundary by the Clinical Safety pillar, their severity ratings, and the controls the clinician is personally responsible for

- Crossing Choreography Fluency — the sender, receiver, and bilateral pre-conditions for each crossing type at this boundary, and the minimum governance for informal crossings

- Escalation Protocol Knowledge — what to do when pre-conditions cannot be met, who to contact, what information to provide, and who holds responsibility during the escalation interval

- Constitutional Literacy — which regulatory body governs the professional on the other side of this boundary, what their service specification permits, and how their contractual framework differs

- Documentation Competence — how to record boundary crossings in a way that satisfies audit requirements for both organisations and feeds into the Clinical Safety pillar’s monitoring

Why boundary competence is boundary-specific

The temptation is to develop a generic boundary competence framework — a training module that covers “working across organisational boundaries” in the abstract. This temptation must be resisted, because boundary competence that is not specific to a particular boundary is not boundary competence at all. It is governance awareness, which is useful but insufficient.

The governance architecture at the GP-to-community-Trust boundary is different from the architecture at the GP-to-VCSE boundary. Different data controller relationships. Different DSPT assurance levels. Different contractual frameworks. Different Clinical Safety Officer arrangements. Different hazard profiles. Different crossing types. Different pre-conditions. A clinician trained in the abstract principle that “you should check data sharing is lawful before sharing information across an organisational boundary” has been given a principle. A clinician told that “when you share information with the VCSE link worker in Room 4, there is no formal data sharing agreement in place, the VCSE organisation has no DSPT assessment, and you should limit sharing to the minimum necessary for the specific purpose and confirm this with the patient” has been given something they can act on.

Boundary competence is therefore developed per boundary. Each bilateral boundary in the neighbourhood health centre generates its own competence requirement, informed by the Legal, Clinical Safety, and Process pillars for that boundary. The competence framework for the GP-to-pharmacy boundary is different from the framework for the GP-to-community-Trust boundary, because the governance architecture is different.

This sounds burdensome. In practice, it produces targeted, specific briefings rather than generic training modules. A clinician who works at two boundaries (say, the GP-to-community-Trust boundary and the GP-to-pharmacy boundary) needs two boundary-specific briefings, each of which translates the governance architecture into actionable knowledge for the crossings they make every day. This is more useful and less time-consuming than a generic multi-hour training module on “information governance in multi-organisational settings.”

The constitutional knowledge gap

The fourth article in this series established that a neighbourhood health centre contains up to five distinct constitutional domains — general practice, community Trust, mental health Trust, community pharmacy, and VCSE. Each domain is governed by different legislation, regulated by different bodies, subject to different contractual frameworks, and constitutionally independent from every other domain.

The People pillar requires clinicians to understand, at a practical level, the constitutional architecture of the building they work in. Not constitutional law in the academic sense. But the operational implications: that the community pharmacy next door is regulated by the GPhC, not by CQC, and its clinical governance obligations differ from the Trust’s. That the VCSE link worker is not employed by the NHS and may not be subject to the same regulatory framework, the same mandatory training requirements, or the same incident reporting obligations. That the mental health practitioner, though co-located and part of the “neighbourhood team,” is employed by a different Trust, works to a different clinical governance framework, and has a different reporting line from the community nurse sitting beside them.

Without this constitutional knowledge, clinicians make assumptions. They assume the co-located team operates under a shared governance framework because it feels like a shared team. They assume that information shared in a “team meeting” is governed by the same rules regardless of which organisation each participant belongs to. They assume that clinical responsibility follows the patient through the building, regardless of which organisation’s service the patient is currently receiving.

Every one of these assumptions is wrong. And every one of them is entirely reasonable for a clinician who has been told they work in a “neighbourhood team” but not told what that means constitutionally.

Professional regulation at the boundary

Different professions at a neighbourhood health boundary are subject to different regulatory bodies: the GMC for doctors, the NMC for nurses and midwives, the HCPC for allied health professionals, the GPhC for pharmacists. Each regulator sets its own professional standards, its own requirements for handover and continuity of care, its own expectations for delegation and referral.

Good Medical Practice 2024 — the GMC’s updated guidance — strengthened the requirements around handover and responsibility transfer. Doctors must check, where practical, that a named clinician or team has taken over responsibility when their role in a patient’s care has ended. The GMC’s detailed guidance on delegation and referral, updated in January 2024, specifies duties when referring a patient or delegating care, and obligations when taking over responsibility.

These standards are clear within a single regulatory framework. At a neighbourhood boundary, regulatory frameworks intersect. A GP (GMC-regulated) refers to a pharmacist (GPhC-regulated) who escalates to a community nurse (NMC-regulated) who involves a VCSE support worker (potentially unregulated). Each professional’s regulatory obligations shape what they must do at the boundary — but those obligations were defined by regulators working independently, not by regulators who sat down together to agree how their respective standards interact at an organisational crossing.

The People pillar does not resolve regulatory misalignment — that is beyond any single neighbourhood’s authority. But it does require that clinicians at each boundary understand the regulatory obligations of the professionals on the other side. A GP who refers to a pharmacist should understand that the pharmacist’s professional obligations under GPhC standards may define what the pharmacist can and cannot do with the referral in ways the GP might not expect. A community nurse who receives a patient from a VCSE link worker should understand that the link worker may not be subject to the same professional duty of candour, the same incident reporting obligations, or the same clinical governance requirements.

Understanding what the other side is required to do — and not required to do — is essential to making the boundary crossing work. Without it, each professional operates according to their own regulatory framework and assumes the other side is doing the same. They often are not, because “the same” does not exist across regulatory boundaries.

Induction, not just training

Boundary competence is not a one-off training module. It is an induction requirement — something that every clinician who works at a specific boundary must receive before working at that boundary. And it must be refreshed when the governance architecture changes, when new crossing types are introduced, when hazard assessments are updated, or when incidents reveal that the existing competence framework is insufficient.

The distinction between training and induction matters. Training develops skills and knowledge that transfer across contexts. A clinician trained in communication skills can apply those skills at any boundary. Induction provides context-specific information that enables a person to work safely in a specific environment. A clinician inducted into the governance architecture of the GP-to-mental-health-Trust boundary knows the specific legal framework, the specific hazards, the specific choreography, and the specific escalation pathways for that boundary.

Current NHS induction programmes are organisation-centric. A new community nurse receives induction into the Trust’s policies, the Trust’s systems, the Trust’s incident reporting pathway, the Trust’s clinical governance framework. If she is deployed to a neighbourhood health centre, she may receive additional induction covering the physical environment, the co-located services, and the collaborative working arrangements. She is unlikely to receive induction into the governance architecture of each boundary at which she will work — the data controller relationships, the specific hazards, the crossing choreography, the escalation pathways — because that governance architecture has not been defined, and therefore cannot be taught.

This is the dependency that makes the People pillar fourth in the Boundary Readiness model’s ordering. The People pillar requires the Legal pillar (to define what clinicians must know about data controller architecture), the Clinical Safety pillar (to define what clinicians must know about boundary hazards), and the Process pillar (to define what clinicians must know about crossing choreography) before it can develop boundary-specific induction. Without the preceding three pillars, there is nothing specific to teach — only generic principles that sound helpful in a training room and dissolve on contact with the governance reality of a co-located building.

The corridor conversation revisited

The fifth diagram in this series illustrated the corridor conversation — the informal clinical interaction that co-location makes so natural. Diagram 5 showed that what feels like a simple conversation between colleagues is actually seven governance questions, all unanswered.

The People pillar is what transforms that corridor conversation from an ungoverned interaction into a governed one. Not by eliminating it — corridor conversations are clinically valuable and will happen regardless of any governance framework. But by ensuring that the people having the conversation know what it is.

A GP who has received boundary-specific induction knows that when she discusses a patient with the co-located mental health practitioner, she is crossing an organisational boundary. She knows that the interaction requires, at minimum, the patient’s awareness, a brief documentation note in both records, and clarity about whether clinical responsibility is being shared, transferred, or retained. She knows these things not because she has studied constitutional law but because someone told her, specifically and practically, what the governance architecture of this particular boundary requires of her in this particular type of interaction.

The People pillar does not create bureaucracy. It creates knowledge. Bureaucracy is what happens when governance requirements are imposed without explanation — when clinicians are told to complete forms without understanding why. Knowledge is what happens when clinicians understand the governance architecture well enough to apply it with judgement. A clinician with boundary competence knows when the corridor conversation is straightforward (informal advice, no responsibility transfer, no personal data shared) and when it is not (clinical decision-making, shared or transferred responsibility, personal data crossing a controller boundary). She can make that distinction because she understands the architecture. And she can act on it because the Process pillar has defined what minimum governance each type of interaction requires.

The People pillar assessment

The People pillar assessment at Inference Clinical covers four domains at each bilateral boundary.

First, boundary competence definition — whether a boundary-specific competence framework exists for each bilateral boundary, covering legal literacy, clinical safety awareness, crossing choreography knowledge, and escalation competence. The framework must be derived from the Legal, Clinical Safety, and Process pillars for that boundary — not from generic governance principles.

Second, induction coverage — whether every clinician who works at a boundary has received boundary-specific induction covering the competence framework for that boundary. This includes not just permanent staff but locums, temporary staff, students, and any other clinician who may initiate or receive a crossing at that boundary. A locum GP covering a Saturday session in a neighbourhood health centre has the same boundary governance requirements as the permanent partner — and needs the same induction, even if time-constrained and appropriately abbreviated.

Third, constitutional awareness — whether clinicians at each boundary understand the constitutional architecture of the organisations on the other side. Do they know which regulatory body governs the professional on the other side of the boundary? Do they understand the contractual framework under which the other organisation operates? Do they know the limits of what the other organisation’s service specification permits? Constitutional ignorance at boundaries is the root cause of clinical intent mismatches, escalation failures, and responsibility transfer gaps.

Fourth, competence maintenance — whether the boundary competence framework is updated when the governance architecture changes, and whether clinicians are informed of changes that affect their boundary. A new data sharing agreement at the GP-to-pharmacy boundary changes the legal architecture — and therefore changes what the GP and the pharmacist need to know. A new hazard identified at the GP-to-mental-health-Trust boundary changes the clinical safety architecture — and therefore changes what clinicians at that boundary need to be aware of. If the competence framework is static while the governance architecture evolves, the People pillar degrades over time.

The private sector parallel

In private healthcare, the People pillar has a distinctive challenge: the workforce at organisational boundaries is often less stable than in NHS settings. Consultant specialists working across multiple private hospitals and clinics, agency nurses filling gaps in staffing, and administrative staff managing referrals between providers and insurers — all work at boundaries without necessarily receiving boundary-specific induction for each setting.

The principle remains constant. Every clinician who works at an organisational boundary needs to understand the governance architecture of that boundary. In private healthcare, where the contractual and regulatory frameworks differ from the NHS (no DSPT requirement, no Caldicott Guardian mandate, different CQC registration arrangements), the boundary competence framework must reflect those differences. A consultant who accepts a private referral from an insurer’s triage service should understand the data controller relationship between the insurer and their practice, the contractual obligations governing what clinical information must be shared back with the insurer, and the professional responsibilities governing patient confidentiality when the insurer requests clinical detail for utilisation review purposes.

The commercial dimension adds a layer that NHS boundaries do not have. The People pillar in private healthcare must address not just clinical governance at boundaries but the intersection of clinical governance and commercial governance — particularly around pre-authorisation, claims processing, and the flow of clinical information between providers and payers.

What the People pillar is not

The People pillar is not MDT development. It does not replace the clinical and interpersonal competencies that multi-disciplinary team training develops. It adds a layer that MDT training does not cover: the governance competencies required to work safely across organisational boundaries.

It is not information governance training. IG training covers general principles of data protection and confidentiality. The People pillar covers the specific application of those principles at specific boundaries.

It is not a substitute for good clinical judgement. Boundary competence does not tell clinicians what clinical decisions to make. It tells them what governance framework those clinical decisions must operate within, and what to do when the framework and the clinical need conflict.

And it is not optional. Of the five pillars in the Boundary Readiness model, the People pillar is the one that determines whether the governance architecture actually functions in practice. Legal, Clinical Safety, and Process can be meticulously defined, documented, and approved. If the people who work at boundaries do not understand them, they are policy documents in a folder — not operational governance.

The People pillar is where architecture becomes behaviour.

The final article examines the Technology pillar: why interoperability that does not preserve provenance and clinical intent is interoperability in name only, how digital infrastructure can enforce or undermine boundary governance, and what MVRT-capable systems actually require.

Architecting Neighbourhood Health Series

- What the Implementation Programme Is Missing

- Mapping the Seven Flows in a Neighbourhood Health Centre

- Clinical Responsibility Transfer — Why Handover Frameworks Don’t Cross Organisational Boundaries

- Constitutional Complexity — Five Organisations, Five Legal Frameworks, One Building

- Boundary Readiness — Why “People, Process, Technology” Fails at Healthcare Boundaries

- The Legal Pillar — Data Sharing, Contractual Frameworks, and Constitutional Compliance

- The Clinical Safety Pillar — When the Hazard Sits Between Organisations

- The Process Pillar — Crossing Choreography and the Pre-Conditions Nobody Defines

- The People Pillar — Why Generic MDT Training Doesn’t Cross Organisational Boundaries (current)

- The Technology Pillar — Why Interoperability That Doesn’t Preserve Governance Is Interoperability in Name Only

Inference Clinical’s Seven Flows Boundary Governance Audit assesses the People pillar at every bilateral boundary — boundary competence definition, induction coverage, constitutional awareness, and competence maintenance. To assess whether the people at your boundaries understand the governance architecture they work within, book a scoping call.