Key Takeaways

- The neighbourhood health model is the centrepiece of the NHS Ten Year Health Plan — but the governance conversation focuses on committee structures and accountability frameworks, not on what happens at clinical boundaries when responsibility transfers between organisations.

- Co-location changes the patient experience but does not change the legal architecture. Every organisation in a neighbourhood health centre retains its own CQC registration, data controller status, and clinical governance structure.

- Informality is more dangerous than formal referral. Corridor conversations between co-located clinicians are legally inter-organisational referrals with no structured record, no documented responsibility transfer, and no outcome feedback.

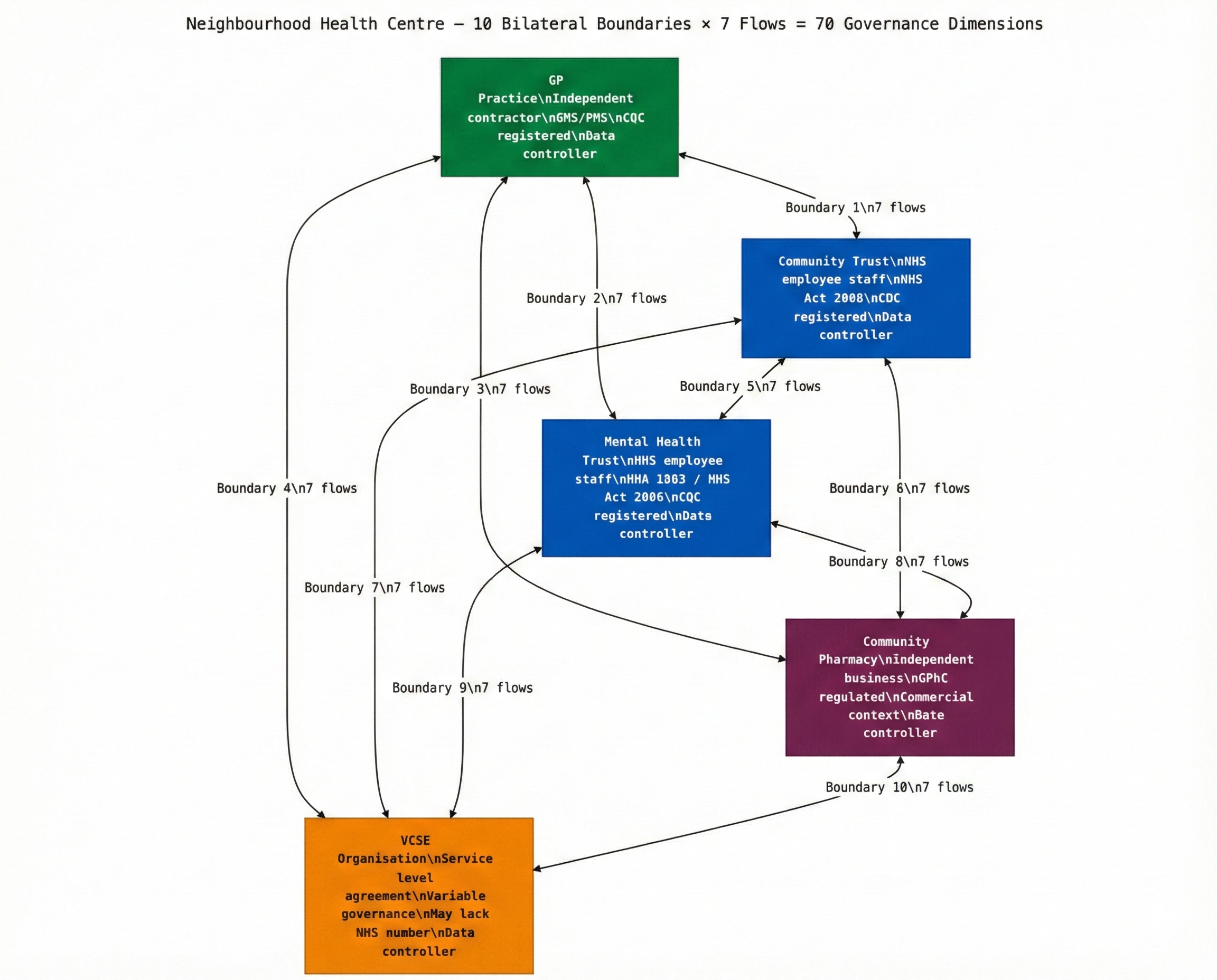

- Five organisations in a neighbourhood centre create up to ten bilateral boundaries and seventy governance dimensions across the Seven Flows. The NNHIP's four enabler groups address none of them.

- Three things are required before pilots scale: boundary mapping before operational launch, MVRT as a design requirement, and outcome flow by design.

The neighbourhood health model is the centrepiece of the NHS Ten Year Health Plan. The vision is compelling: GPs, community nurses, mental health teams, pharmacists, allied health professionals, and voluntary sector organisations brought together in shared spaces, serving defined populations of 30,000 to 50,000 people. Integrated, accessible, community-centred care.

The implementation programme is accelerating. Forty-three places now form part of the National Neighbourhood Health Implementation Programme. ICBs are mapping neighbourhoods. New single neighbourhood provider and multi-neighbourhood provider contracts are due to launch in 2026. Estates are being assessed. Service specifications are being drafted.

And the governance conversation is happening. But it is the wrong governance conversation.

The governance everyone is discussing — and the governance gap inside the building

There is no shortage of governance thinking around neighbourhood health. The NHS Confederation has published detailed analysis of the operating model — the three-tier architecture of System, Place, and Neighbourhood, the role of Integrated Care Boards, the relationship between single neighbourhood providers and multi-neighbourhood providers, the position of Health and Wellbeing Boards. Matthew Taylor, chief executive of the NHS Confederation, has warned that the neighbourhood health service risks becoming a “conceptual muddle” — too many objectives, different stakeholders focusing on different goals, with the danger that ambition never translates into implementation.

Primary care leaders are asking the right structural questions: who sits on what board, who holds which contract, how is information fed up and down, and — critically — “where accountability actually lands when things go wrong.”

NHS England London has gone further than most, publishing a targeted operating model that calls for “updated clinical governance and risk management including protocols to oversee care quality and patient safety, particularly during transitions and across interfaces” and “clinical accountability plans for every INT, detailing responsibilities across teams and outlining protocols for shared care and handovers.”

This is all important work. But notice what it addresses: committee structures, accountability frameworks, reporting lines, escalation protocols, contract models. It asks who is responsible for what at the organisational level.

It does not address what happens at the clinical boundary when the GP in a neighbourhood health centre hands responsibility for a patient to the mental health practitioner in the next room. It does not address whether that handover is recorded, bilateral, and subject to clinically-timed escalation. It does not address whether the patient’s identity is verified across different clinical systems, whether consent has been propagated for the specific crossing, whether clinical intent is communicated in structured form, or whether the originating clinician ever learns the outcome.

The governance conversation is about structure. The gap is about boundaries.

Co-location changes the experience — not the legal architecture

The neighbourhood health model rests on an intuitive assumption: that bringing services together physically will reduce complexity. If the GP, the community mental health nurse, and the pharmacist all share a building, care becomes seamless. The patient doesn’t need to navigate between organisations. Clinicians can collaborate in real time. Information flows naturally.

This assumption is correct about the patient experience. It is wrong about the governance.

The NHS Confederation’s analysis of the neighbourhood model identifies the core components: general practice at the forefront, neighbourhood provider contracts, integrated neighbourhood teams, VCSE sector involvement, community pharmacy. It rightly notes that “neighbourhood working is both a mindset and method” and that the model requires “integrated health and care services and a workforce at the most local level.” But it describes integration as an operating model — not as a governance challenge at the organisational boundary.

Every organisation in a neighbourhood health centre retains its own legal identity. The GP practice is an independent contractor under GMS/PMS. The community nurses are employed by the NHS Trust. The mental health team may sit under a different Trust entirely. The pharmacist operates as an independent business under GPhC regulation. The voluntary sector organisations operate under their own governance frameworks, often with service level agreements rather than statutory instruments.

The new SNP contract adds a further layer. The NHS Confederation confirms that single neighbourhood providers “can also be held by acute, community, or mental health trusts” — meaning the contract-holder coordinating neighbourhood services may be a fundamentally different type of organisation from the GP practices and VCSE bodies delivering care within it. The SNP contract creates an additional organisational boundary at the heart of the neighbourhood model: between the contract-holder’s governance framework and each participating provider’s independent obligations.

Co-location changes the operational experience. It does not change the legal architecture. When the GP asks the community nurse to review a patient, that is an inter-organisational referral between two separate data controllers, two separate CQC registrations, two separate clinical governance structures. The data sharing requires lawful basis. The responsibility transfer requires governance. The clinical intent needs to be communicated. The outcome needs to be captured.

What co-location does change is visibility. And this is where it becomes more dangerous, not less.

Why the corridor conversation is more dangerous than the e-RS referral

In the current system, a GP referring a patient to a hospital specialist generates a formal referral. It may be imperfect — the clinical intent may be poorly communicated, the responsibility transfer may be implicit — but at least a record exists. The referral enters a booking system. There is a timestamp, a sender, a recipient, and a documented clinical reason.

In a neighbourhood health centre, the GP walks down the corridor and asks the mental health practitioner to see a patient. The interaction feels like a conversation between colleagues. There may be no formal referral. No structured record of what was asked. No documented transfer of clinical responsibility. No mechanism for the GP to learn the outcome.

Legally, this corridor conversation is a data transfer between independent controllers with an implicit responsibility handover. Clinically, it is the point at which a patient’s care moves from one governance framework to another. In governance terms, it is completely invisible.

Why are corridor conversations a clinical governance risk?

In a co-located neighbourhood health centre, informal corridor conversations between clinicians from different organisations act as undocumented inter-organisational referrals. They lack lawful basis for data sharing, structured clinical intent recording, explicit responsibility transfer, and outcome feedback. The informality masks what is legally a boundary crossing between separate data controllers, separate CQC registrations, and separate clinical governance frameworks.

This is the pattern that makes neighbourhood health centres a governance challenge of a different order from traditional referral pathways. The volume of boundary crossings increases dramatically — every multi-disciplinary interaction is a crossing — while the governance infrastructure decreases because the informality of co-location suppresses the mechanisms that formally-structured referrals at least partially provide.

Ten bilateral boundaries inside one building

A traditional GP practice has a relatively limited set of organisational boundaries. It refers to the local acute Trust, to community services, to diagnostic providers, and occasionally to specialist providers. Each boundary can be identified, mapped, and — in principle — governed.

A neighbourhood health centre with five participating organisations creates a fundamentally different picture. Five organisations produce up to ten bilateral boundaries. Each boundary engages what we call the Seven Flows — seven dimensions of governance that must function at every organisational crossing: Identity, Consent, Provenance, Clinical Intent, Alert & Responsibility, Service Routing, and Outcome.

That is up to seventy governance dimensions across one neighbourhood centre. And the Ten Year Plan envisions these centres across every neighbourhood in England.

The mathematics gets worse when you consider that neighbourhood health centres don’t exist in isolation. Each participating organisation also has boundaries with external organisations — the acute Trust, the diagnostic network, the ambulance service, social care. The neighbourhood centre doesn’t replace these external boundaries. It adds internal boundaries on top of them.

A community mental health nurse in a neighbourhood centre now operates across three categories of boundary: within the centre (to the GP, to the pharmacist, to the voluntary sector), within her employing Trust (to inpatient services, to crisis teams, to CAMHS), and externally (to the acute Trust, to social care, to the police via Section 136). Each category requires governance. The first category — the neighbourhood centre’s internal boundaries — currently has no governance framework at all.

What the Seven Flows reveal inside a neighbourhood health centre

At Inference Clinical, we built the Seven Flows Boundary Governance Audit specifically for inter-organisational boundaries. When we apply our framework to the neighbourhood health model, three structural problems emerge — none of which are addressed by the governance frameworks currently being discussed.

NHS England London’s operating model calls for “protocols to oversee care quality and patient safety, particularly during transitions and across interfaces”. This is the right language. But what does “across interfaces” mean in practice? What does the protocol look like? How do you assess whether the interface is governed? Our methodology answers these questions with specificity — seven dimensions of governance, each scored at each boundary, with cascading failure logic that reveals structural dependencies.

The Identity flow fractures across systems. Each organisation in a neighbourhood centre may use different clinical systems. The GP practice uses EMIS or SystmOne. The community Trust may use Rio, Carenotes, or a different EPR entirely. The pharmacist uses a dispensing system. The voluntary sector organisation may use a spreadsheet.

When a patient is discussed across these organisations, the Identity flow — can both parties verify who the patient is at the point of data exchange? — depends on whether the systems can share a common patient identifier. NHS number provides this for NHS-funded services. But voluntary sector organisations may not have NHS number access. Private or third-sector providers operating under SLAs rather than NHS contracts may use their own identifiers. In our scoring model, if Identity falls below Level 2 at a boundary, Consent and Provenance are automatically capped — because you cannot meaningfully verify consent or data provenance for a patient whose identity you haven’t independently confirmed at the point of crossing.

Alert & Responsibility transfer is structurally absent. This is the critical failure. In a neighbourhood centre, responsibility for a patient’s care shifts constantly between organisations during a single visit. The GP identifies a mental health concern and asks the mental health practitioner to assess. The mental health practitioner recommends a medication change and asks the pharmacist to review. The pharmacist identifies a contraindication and flags it back to the GP.

At each handover, clinical responsibility transfers. But there is no infrastructure to enforce Minimum Viable Responsibility Transfer — no explicit bilateral handover, no confirmed acceptance, no clinically-timed escalation if acceptance doesn’t occur. In our methodology, MVRT is the normative control for Alert & Responsibility: a boundary that cannot demonstrate explicit, bilateral responsibility transfer cannot score above Level 2, and the boundary governance rating is floored to “Not Assured” if this critical flow fails.

In the corridor conversation model, MVRT is structurally impossible. There is no system to confirm that the mental health practitioner has accepted clinical responsibility for the aspect of care the GP has referred. There is no mechanism to identify patients who are “in transit” between clinicians with no named responsible professional. There is no escalation pathway if the handover is not acknowledged. Our technology assessment examines which clinical coordination platforms can enforce bilateral confirmation — and which create the illusion of handover without the governance.

The Outcome flow doesn’t exist. After the mental health practitioner assesses the patient and makes recommendations, does the GP learn what happened? In a co-located setting, the GP might walk back down the corridor and ask. But there is no structured mechanism for outcome reporting across the organisational boundary. The GP’s clinical governance system doesn’t capture outcomes from the mental health team’s intervention. The mental health team’s governance system doesn’t report back to the referring GP.

This is the Outcome flow — the seventh of our Seven Flows — and it is the one most likely to score zero at neighbourhood centre boundaries. Without it, the GP has no feedback loop. They cannot know whether their referrals to the mental health team are appropriate, whether the interventions are effective, or whether the boundary is functioning safely. The same failures repeat because no governance system captures them.

The constitutional complexity within a single building

Neighbourhood health centres don’t just create more boundaries. They concentrate multiple constitutional domains in one physical space.

In our methodology, we identify ten constitutional domains — types of organisation defined by their statutory mandate, regulatory authority, and institutional orientation. A neighbourhood health centre may contain four or five of these within a single building:

1. NHS Trust Staff (community nurses, health visitors, district nurses)

The community Trust staff operating under the NHS Act 2006, regulated by CQC and NHS England, subject to the NHS Standard Contract.

2. Primary Care (the GP practice as independent contractor)

The GP practice operating as an independent contractor under GMS/PMS, regulated by CQC, with significant operational and data controller independence.

3. Community Pharmacy (independent business in a clinical building)

The pharmacist operating as an independent business under GPhC regulation, processing clinical data within a retail commercial environment. A constitutional hybrid.

4. VCSE Organisation (the social prescriber with a service level agreement)

Voluntary and community organisations operating under service level agreements, with variable governance frameworks, potentially holding sensitive clinical data without the governance infrastructure of statutory providers.

5. Digital Health Platforms (the shared coordination layer)

If the neighbourhood centre uses a shared digital platform for coordination, that platform may itself constitute a separate constitutional domain with its own data controller status. Assess the digital governance of shared neighbourhood platforms.

Our Constitutional Transition Matrix maps the risk level for every crossing between these domains. GP-to-NHS Community Trust is LOW risk (similar statutory basis). GP-to-VCSE is MEDIUM-HIGH (different governance frameworks, variable data protection maturity). GP-to-Community Pharmacy involves a care-to-commercial constitutional transition that most neighbourhood health governance planning doesn’t recognise.

When a GP shares clinical information with a community pharmacist for a medication review, the data crosses from a care context into a commercial retail context. The pharmacist is CQC-registered for clinical services but operates a business that also sells products, collects customer data, and may be part of a corporate pharmacy chain. The constitutional boundary is real, even though the pharmacist is twenty feet away.

The private sector parallel

This governance challenge is not unique to the NHS. Private healthcare operates across analogous boundaries, often with less standardised infrastructure.

A private hospital group that co-locates a GP practice, a diagnostic imaging suite, a physiotherapy service, and a consultant outpatient clinic in a single building faces the same structural problem. Each service may have separate CQC registration, separate data controller status, and separate clinical governance. The corporate brand creates an illusion of integration. The regulatory architecture remains fragmented.

When a PE firm acquires multiple healthcare providers and physically co-locates them, the governance challenge intensifies. Boundaries that were previously external — with formal data sharing agreements, referral protocols, and documented governance — become internal and informal. The assumption is that corporate ownership eliminates the boundary. The regulatory reality is that it doesn’t. And the informality of internal processes may actually degrade the governance that previously existed.

Private insurer networks face a version of the same problem at scale. An insurer building an integrated care pathway across a network of approved providers creates boundaries at every handover. The patient moves from the insurer’s triage platform to a private GP, to a diagnostic provider, to a specialist, to a rehabilitation service — each a separate organisation, each a separate data controller, each a boundary requiring governance. The insurer’s network contract governs the commercial relationship. It rarely governs the clinical boundary.

What ICBs need before the neighbourhood centres open

The National Neighbourhood Health Implementation Programme is moving forward with 43 places. ICBs are designing models. Estates are being identified. Service specifications are being written. NHS England London’s targeted operating model calls for “clinical accountability plans for every INT” — which is exactly the right instinct. But clinical accountability at the boundary requires more than a plan. It requires a methodology for identifying boundary-specific risks, a scoring model for assessing governance maturity at each crossing, and infrastructure that enforces governance rather than hoping clinicians remember to follow process.

The NNHIP has four enabler groups — data/digital, finance, estates, and workforce. None of them is focused on boundary governance. None of them is asking: at the organisational boundaries within each neighbourhood, do the seven dimensions of governance function? Is identity verified across systems? Is consent propagated? Is responsibility explicitly transferred? Does the originating clinician learn the outcome?

Matthew Taylor is right that the neighbourhood health service risks conceptual muddle. But the muddle is not only conceptual. It is structural, and it sits at the boundaries between the organisations that will deliver neighbourhood care. The time to address it is now — before the model scales, before informal practices harden into institutional habits, and before a serious incident at a neighbourhood boundary forces a retrospective governance framework.

Three requirements for ICB governance assurance

Boundary mapping before operational launch. Every neighbourhood health centre should map its organisational boundaries before it opens. Which organisations participate? What are the bilateral boundaries between them? Which constitutional domains are engaged? What are the data flows at each boundary? This is not a bureaucratic exercise. It is the foundation for every governance decision that follows. Our Seven Flows methodology provides a structured framework for this mapping — seven dimensions of governance assessed at each boundary, with constitutional analysis applied to every cross-domain crossing.

MVRT as a design requirement, not a retrofit. The infrastructure for neighbourhood health centres should enforce Minimum Viable Responsibility Transfer from day one. Every clinical handover between organisations within the centre should be recorded, bilateral, and subject to clinically-timed escalation. This means the shared systems or coordination platforms used within the centre must be designed to enforce governance, not just facilitate communication. A shared Microsoft Teams channel is not MVRT. A structured handover protocol with confirmed acceptance, recorded in both organisations’ clinical systems, is.

Outcome flow by design. The governance framework for neighbourhood health centres should require structured outcome reporting across internal boundaries. When the GP refers to the mental health team, the mental health team’s outcome should flow back to the GP in structured form. When the pharmacist identifies a contraindication, the resolution should be captured and reported back to the referring clinician. Without this feedback loop, the neighbourhood centre has no mechanism for learning, improvement, or safety governance across its internal boundaries.

What CQC will look for at neighbourhood health boundaries

CQC’s single assessment framework applies to every registered provider within a neighbourhood health centre independently. But the boundary between those providers is where governance risk concentrates. When CQC assesses a neighbourhood model, the following questions will arise at every organisational crossing:

- Safe care (Regulation 12) — can the receiving organisation demonstrate that clinical handovers from co-located partners are documented, with clinical intent recorded and responsibility explicitly transferred?

- Good governance (Regulation 17) — does each participating organisation have a governance framework that covers its boundaries with other co-located providers, not just its internal operations?

- Person-centred care (Regulation 9) — has the patient been informed that their care involves multiple independent organisations with separate data controllers, even though they appear to be in a single service?

- Consent (Regulation 11) — does the consent framework cover inter-organisational data sharing within the neighbourhood centre, not just internal processing within each provider?

- Duty of candour (Regulation 20) — when a safety incident occurs at a boundary between two co-located organisations, which organisation owns the duty of candour obligation, and is this agreed in advance?

- Staffing and fit and proper persons (Regulations 18/19) — when clinicians from different organisations work side by side, are the respective employers’ safeguarding checks and professional registration requirements mutually visible?

The opportunity for the 43 NNHIP pioneer sites

Primary care leaders are rightly asking “where accountability actually lands when things go wrong” in the neighbourhood model. The answer needs to go beyond committee structures and reporting lines. It needs to address the clinical boundary — the point where one organisation’s governance ends and another’s begins, where a patient’s data crosses between systems, where responsibility transfers between clinicians who may be employed by different organisations with different regulators and different statutory obligations.

The organisations and ICBs that address this now — the 43 NNHIP places and the systems designing neighbourhood models around them — will be the ones that demonstrate the model works safely. They will have evidence — structured, scored, statutory-traceable evidence — that their neighbourhood boundaries are governed. They will be able to show CQC that their multi-organisational model has governance not just within each participating organisation, but at the joins between them.

Those that assume co-location is integration will discover, after the first serious incident at an internal boundary, that they have built a model optimised for access and efficiency with a structural blind spot for safety.

The neighbourhood health model is the right direction. The governance infrastructure to make it safe is the missing piece. It needs to be built before the centres open, not after something goes wrong.

Architecting Neighbourhood Health Series

- Architecting for Neighbourhood Health: What the Implementation Programme Is Missing (current)

- Mapping the Seven Flows in a Neighbourhood Health Centre

- Clinical Responsibility Transfer — Why Handover Frameworks Don’t Cross Organisational Boundaries

- Constitutional Complexity — Five Organisations, Five Legal Frameworks, One Building

- Boundary Readiness — Why “People, Process, Technology” Fails at Healthcare Boundaries

- The Legal Pillar — Data Sharing, Contractual Frameworks, and Constitutional Compliance

- The Clinical Safety Pillar — When the Hazard Sits Between Organisations

- The Process Pillar — Crossing Choreography and the Pre-Conditions Nobody Defines

- The People Pillar — Why Generic MDT Training Doesn’t Cross Organisational Boundaries

- The Technology Pillar — Why Interoperability That Doesn’t Preserve Governance Is Interoperability in Name Only

Inference Clinical’s Seven Flows Boundary Governance Audit assesses governance at every organisational boundary — including the internal boundaries that neighbourhood health centres and co-located services create. Per-boundary scorecards with cascading failure logic, constitutional transition analysis, and MVRT compliance assessment. To map and score your neighbourhood boundaries before launch, book a scoping call.