Key Takeaways

- The Legal pillar is foundational — without a lawful basis for data to cross between organisations, every subsequent Boundary Readiness pillar operates on unlawful ground. Technology enables illegal data flows. Processes choreograph illegal transfers. Training teaches staff to perform illegal actions competently.

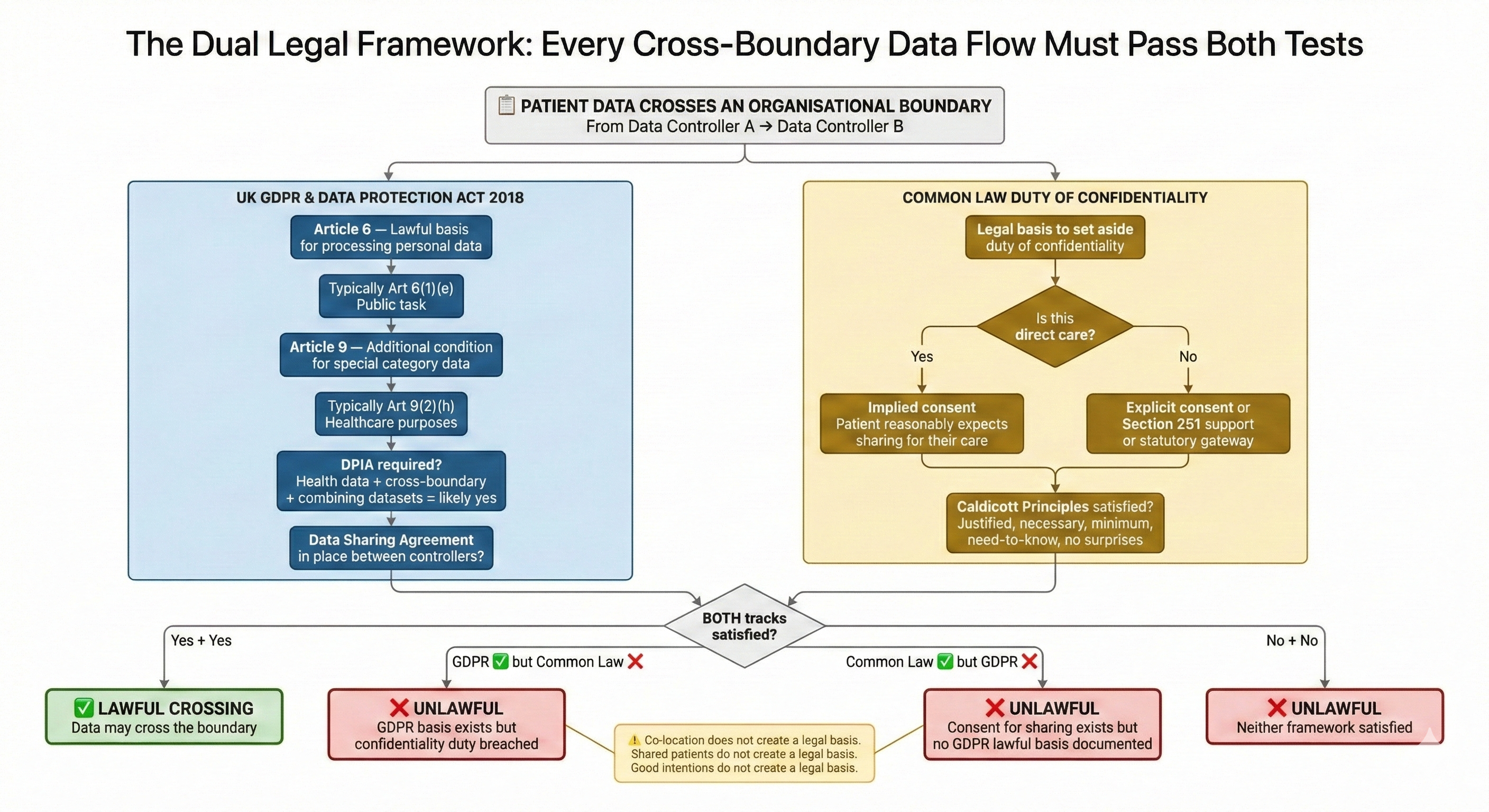

- Healthcare data must satisfy two independent legal regimes simultaneously — UK GDPR (Article 6 + Article 9) and the common law duty of confidentiality. Satisfying one does not satisfy the other. A data flow that is lawful under GDPR can still breach confidentiality, and vice versa.

- Co-location does not create a legal basis — shared patients, good intentions, and being in the same building do not create lawful authority for data to cross between independent data controllers. Each bilateral boundary requires its own data sharing agreements, DPIAs, and dual legal basis mapping.

- The DSPT assesses nodes, not edges — organisations in the same building may sit in three or four different DSPT categories, creating a data security assurance asymmetry at every boundary. The toolkit does not assess whether DSAs, DPIAs, or Caldicott coordination are in place between co-located organisations.

- The Legal pillar assessment covers six domains — data controller status, dual legal basis, bilateral DSAs, boundary-specific DPIAs, Caldicott Guardian coordination, and contractual alignment. Incomplete at any domain means the boundary is not legally ready.

This is the sixth article in the Architecting for Neighbourhood Health series. The first article examined why the current governance conversation addresses committee structures but not boundary governance. The second introduced the Seven Flows that must function at every organisational crossing. The third went deep on clinical responsibility transfer and the MVRT principle. The fourth examined constitutional complexity — what happens when fundamentally different types of organisation share a building and a patient population. The fifth introduced the Boundary Readiness model that replaces People, Process, Technology with five pillars assessed in dependency order at every bilateral boundary.

The Legal pillar answers a single question: may this boundary crossing happen? Not whether it should happen clinically, or whether the technology supports it, or whether staff understand the process — but whether the legal architecture exists to permit it. Without a lawful basis for data to cross between two organisations, every subsequent pillar of Boundary Readiness operates on unlawful ground. The technology enables illegal data flows. The processes choreograph illegal data transfers. The training teaches staff to perform illegal actions competently. Legal is first because it is foundational. Get it wrong, and nothing built on top of it is safe.

What is the Legal Pillar of Boundary Readiness?

The Legal Pillar is the first and foundational pillar of the Boundary Readiness model. It assesses whether the legal architecture exists to permit data to cross between two independent healthcare organisations — covering UK GDPR lawful basis, common law duty of confidentiality, data sharing agreements, DPIAs, Caldicott Guardian coordination, and contractual alignment at every bilateral boundary. Without the Legal Pillar in place, every subsequent pillar operates on unlawful ground.

This sounds straightforward. In practice, the legal architecture of a healthcare boundary is one of the most complex governance challenges in the NHS — because healthcare data in England is not governed by one legal framework but by two, operating simultaneously, with different requirements, different consent models, and different enforcement mechanisms.

The dual legal framework: UK GDPR and common law at NHS neighbourhood boundaries

Every cross-boundary data flow in healthcare must satisfy two independent legal regimes at the same time. The first is the UK GDPR and Data Protection Act 2018, which governs the processing of personal data. The second is the common law duty of confidentiality, which governs the use and disclosure of information shared in confidence — a regime built not from statute but from centuries of case law.

These two frameworks are not interchangeable. They have different legal bases, different consent mechanisms, and different enforcement routes. A data flow that satisfies UK GDPR can still breach the common law duty of confidentiality. A data flow that has valid consent under common law may still lack a lawful basis under UK GDPR. Both must be satisfied, independently, for every cross-boundary data flow.

The conflict between UK GDPR and Common Law in healthcare

A cross-boundary data flow can be lawful under UK GDPR (for example, under the Public Task basis of Article 6(1)(e)) but unlawful under common law (because the patient’s implied consent does not extend to this specific disclosure). Both legal regimes must be satisfied independently at every organisational boundary — satisfying one does not discharge the other.

Under UK GDPR, health data is classified as special category data requiring dual legal bases: one under Article 6 (lawful basis for processing personal data) and one under Article 9 (additional condition for processing special category data). The ICO has strongly recommended that health and care organisations should not rely on consent as their UK GDPR lawful basis, because consent in a healthcare setting is unlikely to be “freely given” when withholding it could affect the care someone receives. For publicly funded healthcare, the relevant bases are typically Article 6(1)(e) — processing necessary for a task carried out in the public interest — combined with Article 9(2)(h) — processing necessary for healthcare purposes.

Under the common law duty of confidentiality, the legal bases are different. For direct individual care, implied consent normally applies — the patient is understood to expect that clinicians involved in their care will share relevant information. For purposes beyond direct care, explicit consent is required unless a statutory gateway (such as Section 251 of the NHS Act 2006) provides authority to set aside the duty of confidentiality.

Here is where the boundary problem bites. Implied consent for direct care is well established within organisations. A GP shares information with the practice nurse. A hospital consultant shares test results with the ward team. The patient expects this, the common law supports it, and the UK GDPR basis — public task under Article 6(1)(e) — applies cleanly because both parties operate within the same data controller.

At an organisational boundary, the legal architecture changes fundamentally. The patient’s information is now crossing from one data controller to another. The implied consent for direct care may still apply — the NHS Transformation Directorate guidance confirms that implied consent can extend to sharing between organisations for direct care — but the UK GDPR requirements do not collapse just because the common law basis holds. Each organisation must independently establish its own lawful basis for processing. Each organisation must independently satisfy Article 9. Each organisation must independently document and justify its processing.

And there is a harder question that co-location makes urgent: does the patient actually understand that their information is crossing to a different organisation? The eighth Caldicott Principle, introduced in 2020, requires organisations to ensure “no surprises” for patients about how their information is used. In a neighbourhood health centre where the patient sees “the team,” not four independent data controllers, the gap between what the patient expects and what legally happens is significant. The patient tells the GP about their anxiety. The GP walks to the next room and discusses it with a mental health practitioner employed by a different Trust. The patient has not been told that their information is now being processed by a second data controller, under a second governance framework, subject to a second set of retention policies. The common law basis of implied consent rests on the patient’s reasonable expectations — and in a co-located setting, those expectations may not align with the legal reality of what is happening.

Data controller mapping: the foundational legal exercise for co-located healthcare

The fourth article in this series established that a typical neighbourhood health centre contains five constitutional domains — general practice, community Trust, mental health Trust, community pharmacy, and VCSE. Each is an independent data controller under UK GDPR. This means ten bilateral boundaries, each of which requires its own legal architecture. See our full analysis of the 10 constitutional crossings.

Data controller mapping is the first legal exercise because everything else depends on it. Until you have established which organisations are independent controllers, which are joint controllers, and which are processors acting on behalf of controllers, you cannot define the legal basis for any specific data flow. The ICO guidance on controllers and processors is clear that the determination depends on who decides the purpose and means of processing — not on contractual labels, co-location arrangements, or shared branding.

In a neighbourhood health centre, the most likely determination is that each organisation is an independent controller. The GP practice decides what to do with patient data within general practice. The community Trust decides what to do with patient data within its services. The pharmacy decides what to do with patient data within its dispensing and clinical services. These are independent decisions about purpose and means, made by independent organisations, regardless of the fact that they share a building.

This has direct consequences. Independent controllers sharing personal data must have a lawful basis for the sharing (not just for the processing), must have data sharing agreements in place, and must each complete their own Data Protection Impact Assessments where the processing is likely to result in high risk. There is no shortcut. Co-location does not create a legal basis. Shared patients do not create a legal basis. Good intentions do not create a legal basis.

The alternative — that co-located organisations might constitute joint controllers — would require them to jointly determine the purposes and means of processing. This is theoretically possible for specific, defined activities (for example, a jointly commissioned neighbourhood MDT with agreed terms of reference and data processing arrangements), but it would require a formal arrangement under UK GDPR Article 26, with a transparent agreement defining respective responsibilities. In practice, most neighbourhood health centre activities will involve independent controllers sharing data, not joint controllership.

Data sharing agreements at neighbourhood health centre boundaries: bilateral, not blanket

Each bilateral boundary between independent controllers requires a data sharing agreement. This is not a generic document. A DSA must specify the categories of data being shared, the legal basis for sharing, the purposes for which the data will be used by the receiving organisation, retention periods, security measures, and the rights of data subjects.

The NHS England data sharing agreement template provides a framework, but it is designed for defined data flows between named organisations — not for the fluid, corridor-level information sharing that co-location encourages. The gap between the formality of a DSA and the informality of “I’ll just ask the community nurse about this patient” is the legal risk that neighbourhood health centres must address.

A neighbourhood health centre with five organisations requires up to ten bilateral DSAs — one for every pair of organisations that shares patient data. In practice, not every pair will share directly, so the number may be lower. But each DSA that is needed must be specific to that boundary. A GP-to-community-Trust DSA covers different data categories, different purposes, and potentially different legal bases than a GP-to-VCSE DSA. The constitutional distance between the organisations — established in Article 4 of this series — directly determines the complexity of the legal architecture required.

The tiered approach adopted by some ICS regions, such as the Cheshire and Merseyside shared care record DSA, provides a useful model: a Tier Zero overarching agreement establishes common principles, with Tier Two agreements specifying the data flows for particular projects or services. But even tiered models assume that the organisations have been through the process of mapping their data flows, establishing their legal bases, and agreeing their respective responsibilities. In a neighbourhood health centre being designed around estates and co-location, this legal infrastructure must be in place before the first shared clinical interaction occurs.

Checklist for a Neighbourhood Health Data Sharing Agreement

Every bilateral DSA at a neighbourhood health centre boundary must address:

- Purpose specification — the defined purposes for which data will be shared across this specific boundary, not a generic “direct care” catch-all

- Lawful basis (dual) — the UK GDPR Article 6 and Article 9 bases and the common law confidentiality basis for each category of data flow

- Data categories — the specific categories of personal and special category data that will cross the boundary, mapped to the purposes above

- Data controller responsibilities — confirmation that each party is an independent controller (or documentation of joint controllership under Article 26) and their respective obligations

- Retention schedule — retention periods for each data category, noting that each controller’s retention obligations may differ

- Security measures — the technical and organisational safeguards for data in transit across the boundary and at rest in each controller’s systems

- Subject rights — how data subject access requests, rectification, and erasure requests will be handled when data has crossed the boundary

- Breach notification — the protocol for notifying the other party when a breach involves shared data, including timeframes and escalation routes

- Review and termination — scheduled review dates and the process for handling shared data when the agreement ends or an organisation leaves the neighbourhood

DPIAs at the boundary: when cross-boundary data flows require impact assessment

Under UK GDPR Article 35, a Data Protection Impact Assessment is required where processing is “likely to result in a high risk to the rights and freedoms of individuals.” The ICO’s published criteria for mandatory DPIAs include processing of special category data on a large scale, innovative use of technology, and processing that involves combining datasets from different sources.

Cross-boundary data flows in a neighbourhood health centre tick multiple boxes. Health data is special category data by definition. Combining information from GP records, community Trust records, mental health records, and pharmacy dispensing records is combining datasets from different sources. If shared care records or population health management platforms are involved, the innovative technology criterion applies too.

Each data controller must complete its own DPIA for the processing it undertakes — including the processing that involves receiving data from, or sharing data with, other organisations in the building. In practice, this means that a single patient interaction that crosses a boundary between two organisations requires both organisations to have assessed the data protection risks of that crossing, documented the assessment, and implemented appropriate safeguards.

A neighbourhood health centre with five organisations and a shared care record does not need one DPIA. It needs DPIAs from every data controller that participates in the shared processing — and those DPIAs must account for the specific risks at each boundary, not just the risks within each organisation’s own services.

The DSPT asymmetry: why the toolkit does not assess boundary governance

The Data Security and Protection Toolkit is the NHS’s mandatory annual self-assessment for data security. Completion is required for any organisation accessing NHS patient data or systems. But the DSPT is not uniform. It categorises organisations into four tiers with different assessment requirements: Category 1 (large NHS bodies, assessed against the National Cyber Security Centre’s Cyber Assessment Framework), Category 2 (operators of essential services and key IT suppliers), Category 3 (community providers including pharmacies and care homes), and Category 4 (GP practices).

In a neighbourhood health centre, the organisations sharing a building may sit in three or four different DSPT categories. The community Trust is Category 1 — subject to mandatory independent audit and CAF-aligned assessment. The GP practice is Category 4 — completing a less extensive assessment aligned to the National Data Guardian’s ten data security standards. The community pharmacy is Category 3. The VCSE organisation may not be required to complete a DSPT at all unless it is processing NHS patient data under a specific contract.

This creates a data security assurance asymmetry at the boundary. The community Trust has been independently audited against the Cyber Assessment Framework. The VCSE organisation may have no formal data security assessment whatsoever. When patient data crosses from the Trust to the VCSE — in a shared care record, a referral, a verbal handover in a corridor — the data crosses from a high-assurance environment to an environment with potentially no formal assurance at all.

The DSPT does not assess boundary governance. It assesses each organisation’s internal data security posture. It does not ask whether the DSAs are in place between co-located organisations. It does not assess whether DPIAs have been completed for cross-boundary flows. It does not verify that Caldicott Guardians across co-located organisations have coordinated their positions on data sharing. The toolkit assesses the nodes; it does not assess the edges.

Caldicott Guardian coordination across co-located NHS organisations

Every NHS organisation is mandated to have a Caldicott Guardian — a senior person responsible for protecting the confidentiality of patient information and enabling appropriate sharing. The UK Caldicott Guardian Council emphasises that the duty to share information for individual care is as important as the duty to protect confidentiality — the seventh Caldicott Principle, added in 2013 precisely because excessive caution about sharing was harming patient care. Understanding Caldicott Guardian responsibilities in integrated care settings is essential as neighbourhood health models bring multiple organisations into shared clinical space.

In a neighbourhood health centre, each organisation has its own Caldicott Guardian (or should — VCSE organisations are increasingly expected to appoint one). Each Guardian makes independent decisions about what information their organisation can share, with whom, and under what circumstances. There is no hierarchy between them. The community Trust’s Caldicott Guardian has no authority over the GP practice’s data sharing decisions. The GP practice’s Caldicott Guardian has no authority over the pharmacy’s.

When a novel or difficult data sharing decision arises at a boundary — and co-located care will generate these regularly — there is no single point of authority. Two Caldicott Guardians, each with legitimate but potentially different views on whether sharing is appropriate, must reach agreement. If they disagree, there is no escalation route that resolves the disagreement within the neighbourhood. It escalates to the ICB, or to the organisations’ respective boards, or — in the worst case — it doesn’t escalate at all, and clinicians on the ground make their own judgement without the governance support they need.

The Legal pillar of Boundary Readiness requires an explicit Caldicott coordination protocol across co-located organisations. Not a hierarchy — the constitutional independence of each organisation prevents that — but a defined coordination mechanism: regular meetings, agreed decision-making protocols for boundary cases, a shared understanding of each organisation’s position on the common sharing scenarios that co-location creates. Without this Caldicott coordination protocol, each Guardian operates in isolation — making decisions about shared patients without knowing what the other organisations’ Guardians have decided about the same patients.

Contractual frameworks at healthcare boundaries: the unexamined legal layer

Data protection law and common law confidentiality are the legal frameworks most discussed in healthcare information governance. But there is a third legal layer that directly shapes what happens at boundaries: the contractual frameworks that define what each organisation is obligated to provide and what it is permitted to do.

General practice operates under GMS, PMS, or APMS contracts with the ICB. These contracts define the services the practice must provide, the standards it must meet, and the data it must submit. They do not, by default, require the practice to share data with co-located organisations beyond what is necessary for direct patient care. A neighbourhood health centre may assume that co-location implies integration — but the GP contract defines the practice’s obligations, and those obligations are to the ICB, not to the co-located community Trust.

The Single Neighbourhood Provider contract, expected to roll out from 2026, will add a new contractual layer. But as the fourth article in this series established, the SNP contract creates accountability without authority — the contract holder is accountable for neighbourhood outcomes across organisations it does not employ, regulate, or govern. The contractual relationship between the SNP holder and the GP practices within the neighbourhood will define data sharing obligations, performance reporting requirements, and escalation pathways. If those contractual definitions are vague — if they assume that co-location creates integration without specifying the data flows, the legal bases, and the governance mechanisms — the contract will create expectations that the legal architecture cannot support.

Community Trust services are commissioned through NHS Standard Contracts. Community pharmacy operates under the Community Pharmacy Contractual Framework and specific commissioned service specifications. VCSE organisations may be funded through grants, commissioned through service level agreements, or operating as subcontractors to an NHS provider. Each contractual framework creates different obligations and different permissions. A VCSE organisation funded through a grant may have no contractual obligation to share data with the GP practice. A pharmacist delivering Pharmacy First services has a service specification that defines what they can do — but may not define what data they must share with other co-located organisations about what they have done.

The Legal pillar of Boundary Readiness requires mapping not just data protection law and confidentiality obligations, but the contractual framework at every boundary. What does each organisation’s contract require it to share? What does each contract permit it to share? Where contracts are silent on cross-boundary data flows, the silence must be treated as a governance gap — not as implicit permission.

Private healthcare faces the same dual legal framework at organisational boundaries

Private healthcare faces the same dual legal framework — UK GDPR and common law duty of confidentiality — but the contractual layer is different in character. Where NHS organisations are governed by publicly defined contractual frameworks, private healthcare boundaries are governed by commercial contracts between providers, between providers and insurers, and between insurers and their members.

An insurer directing a patient through a network of independent providers — GP, consultant, diagnostic centre, rehabilitation provider — creates a chain of organisational boundaries. Each provider is an independent data controller. Each boundary requires its own legal architecture. The insurer adds a layer: pre-authorisation, utilisation review, and claims processing all involve clinical data crossing from provider to insurer, a boundary that carries both clinical governance and commercial confidentiality requirements simultaneously.

The legal complexity is comparable to the NHS but harder to address because there is no equivalent of the DSPT, no standard DSA template, and no Caldicott Guardian mandate. Private healthcare organisations must build their boundary legal architecture from first principles — which some do well and many do not.

What the Legal pillar assessment requires at every bilateral boundary

At Inference Clinical, the Legal pillar of our Boundary Readiness assessment covers six domains at every bilateral boundary:

First, data controller status — confirming whether each organisation is an independent controller, a joint controller, or a processor, and documenting the basis for that determination.

Second, dual legal basis — establishing the UK GDPR lawful basis (Article 6 and Article 9) and the common law confidentiality basis for each category of data flow across the boundary. These are assessed independently because satisfying one does not satisfy the other.

Third, data sharing agreements — verifying that bilateral DSAs are in place, that they are specific to the boundary (not generic blanket agreements), and that they cover the data categories, purposes, legal bases, retention, security, and subject rights required by both UK GDPR and the common law.

Fourth, DPIAs — confirming that each data controller has completed a DPIA for processing that involves cross-boundary data flows, and that the DPIA addresses the specific risks at that boundary — not just the risks of the processing in general.

Fifth, Caldicott Guardian coordination — assessing whether a coordination mechanism exists between the Caldicott Guardians of co-located organisations, whether it has been tested on boundary-specific sharing decisions, and whether clinicians on the ground know how to escalate novel sharing questions.

Sixth, contractual alignment — mapping the contractual framework at each boundary to identify where contracts create data sharing obligations, where they create permissions, and where they are silent — because silence at a boundary is a governance gap.

Where any of these six domains is incomplete at a boundary, the Legal pillar is assessed as not in place for that boundary — and the Boundary Readiness model says that no subsequent pillar (Clinical Safety, Process, People, Technology) can be assumed to be safe.

Legal first, because everything follows: the foundational pillar of Boundary Readiness

The neighbourhood health implementation programme’s four enabler groups — data/digital, finance, estates, workforce — contain no dedicated legal workstream for boundary governance. The DSPT assesses each organisation’s internal data security but not the legal architecture between organisations. The Caldicott Guardian framework mandates a guardian per organisation but no coordination mechanism across co-located organisations. The contractual frameworks define each organisation’s obligations to its commissioner but not its obligations to its co-located neighbours.

The Legal pillar exists in fragments. Pieces of it sit with information governance teams, Caldicott Guardians, data protection officers, contracting teams, and legal counsel. No single role owns the legal architecture of a boundary — because the boundary sits between organisations, and nobody’s job description covers the space between.

This is why Legal is the first pillar of Boundary Readiness, and why it must be assessed before Clinical Safety, before Process, before People, before Technology. A neighbourhood health centre can have the best clinical safety assessment in the country, the most detailed crossing protocols, the most thoroughly trained staff, and the most interoperable technology — but if the data sharing agreements are not in place, if the DPIAs have not been completed, if the dual legal basis for each cross-boundary flow has not been established, then the centre is operating unlawfully. Competently, perhaps. Collaboratively, certainly. But unlawfully.

The Legal pillar is not exciting. It is not where the energy in neighbourhood health goes. The energy goes to estates, to digital, to workforce. But Legal is the ground on which everything else stands. Assess it first. Assess it at every boundary. And do not assume that co-location creates legality — because it does not.

The next article examines the Clinical Safety pillar: what boundary-specific hazard analysis, DCB 0129/0160 compliance, and CSO coordination look like when the hazard sits between organisations rather than within them.

Architecting Neighbourhood Health Series

- What the Implementation Programme Is Missing

- Mapping the Seven Flows in a Neighbourhood Health Centre

- Clinical Responsibility Transfer — Why Handover Frameworks Don’t Cross Organisational Boundaries

- Constitutional Complexity — Five Organisations, Five Legal Frameworks, One Building

- Boundary Readiness — Why “People, Process, Technology” Fails at Healthcare Boundaries

- The Legal Pillar — Data Sharing, Contractual Frameworks, and Constitutional Compliance (current)

- The Clinical Safety Pillar — When the Hazard Sits Between Organisations

- The Process Pillar — Crossing Choreography and the Pre-Conditions Nobody Defines

- The People Pillar — Why Generic MDT Training Doesn’t Cross Organisational Boundaries

- The Technology Pillar — Why Interoperability That Doesn’t Preserve Governance Is Interoperability in Name Only

Inference Clinical’s Seven Flows Boundary Governance Audit assesses the Legal pillar at every bilateral boundary — dual legal basis mapping, DSA verification, DPIA completeness, Caldicott Guardian coordination, and contractual alignment. To understand the legal architecture of your neighbourhood boundaries, book a scoping call.