Key Takeaways

- Five constitutional domains share a neighbourhood health centre — GP practice, community Trust, mental health Trust, community pharmacy, and VCSE — each constituted under different legislation, regulated by different bodies, and processing patient data under different legal bases.

- Constitutional difference amplifies risk at every Seven Flow boundary — from identity verification (the VCSE may lack NHS PDS access) to outcome measurement (the GP may never learn whether a social prescribing referral was attended).

- The SNP contract adds a sixth constitutional layer without dissolving the five beneath it — creating responsibility without authority, accountability without control.

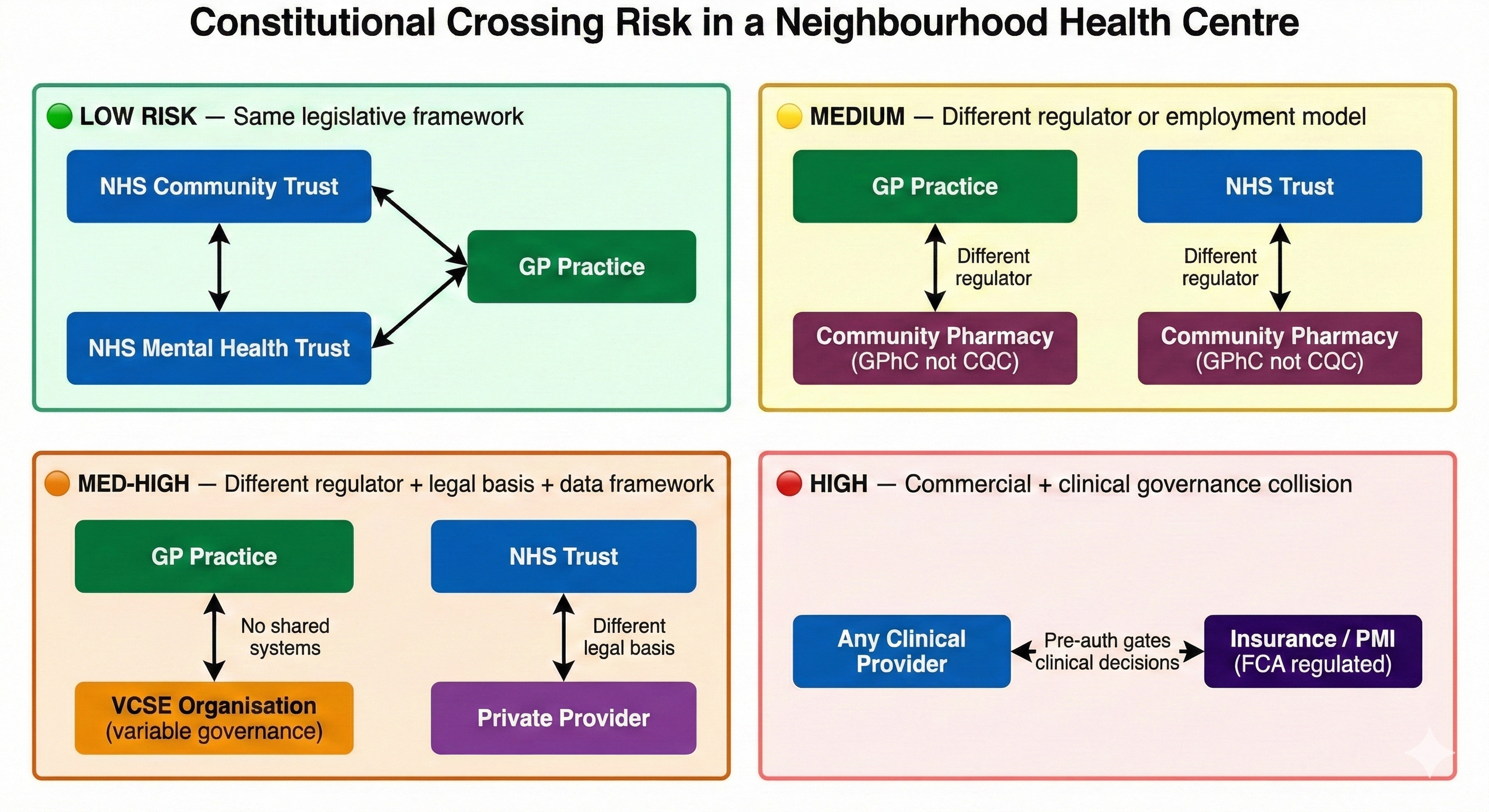

- The constitutional transition matrix reveals that a neighbourhood health centre has ten constitutionally distinct boundaries, each with a different risk profile. Treating them as equivalent is a structural error.

- Four governance requirements must be addressed before co-location: data controller mapping, regulatory alignment assessment, escalation pathway mapping, and Clinical Safety Officer coordination.

This is the fourth article in the Architecting for Neighbourhood Health series. The first article examined why the current governance conversation addresses committee structures but not boundary governance. The second introduced the Seven Flows that must function at every organisational crossing. The third went deep on clinical responsibility transfer and the MVRT principle. This article examines the constitutional dimension — what happens when fundamentally different types of organisation share a building and a patient population.

A neighbourhood health centre, as envisioned in the 10 Year Health Plan, brings together general practice, community health services, mental health, community pharmacy, and voluntary sector organisations under one roof. The language of co-location emphasises unity: “one stop shop,” “multidisciplinary teams,” “joined-up care.” The language of constitutional governance tells a different story entirely.

Each organisation in a neighbourhood health centre is constituted under different legislation, regulated by different bodies, governed by different institutional purposes, employing staff under different terms, and processing patient data under different legal bases. These are not variations on a theme. They are fundamentally different constitutional domains, and every interaction between them crosses a legal boundary that co-location makes invisible but does not dissolve.

What is the constitutional complexity of neighbourhood health?

Constitutional complexity is the governance risk created when multiple independent organisations — NHS Trusts, GP practices, community pharmacies, VCSE bodies — co-locate in a single building, maintaining separate legal identities, separate regulators, and separate data controller statuses while delivering integrated care. The patient experiences “one team”; the law sees five independent entities with five different governance obligations. Every clinical interaction between them crosses a constitutional boundary that co-location makes invisible but does not dissolve.

Five constitutional domains under one neighbourhood health centre roof

Consider a typical neighbourhood health centre. Five organisations share the space. Each exists in a distinct constitutional domain.

1. General Practice (GMS/PMS/APMS)

General practice operates as an independent contractor business, delivering services under GMS, PMS, or APMS contracts with the ICB. The partners are self-employed. The practice is its own data controller under UK GDPR. It is registered with and inspected by CQC. Its clinical governance is internal to the partnership, supplemented by contractual obligations to the ICB. The practice may be part of a PCN, but the PCN itself is not a legal entity — it cannot hold contracts, employ staff, or be regulated in its own right.

2. Community Health Services Trust (NHS Act 2006)

The community health services Trust is a statutory NHS body, established under the NHS Act 2006. Its staff are NHS employees on Agenda for Change terms. It is registered with and inspected by CQC. It has its own board, its own governance structure, its own clinical safety officer, and its own data controller status. Its institutional purpose is defined by its constitution and its provider licence from NHS England.

3. Mental Health Trust (MHA 1983 / MCA 2005)

The mental health Trust is similarly a statutory NHS body, but it operates under additional legislation — the Mental Health Act 1983 and Mental Capacity Act 2005 create specific duties and powers that no other organisation in the building shares. Its staff have particular statutory roles (Approved Mental Health Professionals, Section 12 approved doctors) that carry legal authority the other organisations cannot replicate. It has its own CQC registration, its own governance framework, its own safeguarding pathways, and its own data controller status.

4. Community Pharmacy (GPhC)

The community pharmacy is a private business, regulated not by CQC but by the General Pharmaceutical Council — a completely separate regulatory body with different standards, different inspection cycles, and a different enforcement framework. The regulatory gap between GPhC and CQC standards for clinical services is an active area of debate, with the Pharmacists’ Defence Association arguing that CQC should regulate pharmacy premises to ensure parity. The pharmacy operates in a commercial context. It is its own data controller. Its pharmacist may now be an independent prescriber under the Pharmacy First model, creating clinical decision-making authority that intersects with — but is not governed by — the GP practice’s clinical governance framework.

5. VCSE Organisation (variable governance)

The VCSE organisation is the most constitutionally variable of all. It might be a registered charity, a community interest company, a social enterprise, or an unincorporated association. Its governance framework depends entirely on its legal form. NHS England’s own framework for addressing barriers to VCSE integration explicitly identifies “lack of legal framework or agreements to share data between the NHS and VCSE organisations” as a barrier to integration. Many VCSE organisations lack access to NHS clinical systems. Some may not routinely use NHS numbers as patient identifiers. Their staff may not be subject to the same professional regulation, mandatory training, or clinical supervision requirements as NHS or primary care staff. The King’s Fund has documented the persistent challenge of ensuring the VCSE sector is treated as an integral partner rather than a downstream recipient of referrals.

Five organisations. Five data controllers. At least three different regulators (CQC, GPhC, and the Charity Commission or Companies House depending on VCSE form). Two fundamentally different employment models (independent contractor versus NHS employee). One organisation with unique statutory mental health powers. One operating in a commercial context. One with variable and potentially minimal governance infrastructure.

This is what shares a building in a neighbourhood health centre.

Why constitutional difference amplifies risk at every Seven Flow boundary

The previous articles in this series established that every organisational boundary must be assessed across seven governance dimensions — our Seven Flows. Constitutional difference amplifies the risk at every one of them.

Identity verification across four clinical systems inside one building

Identity appears straightforward until you consider that the VCSE organisation may not have access to the NHS Personal Demographics Service. The community pharmacy verifies identity through its own dispensing systems. The GP practice uses clinical system login and NHS number lookup. When a social prescriber in the VCSE refers a patient to the community pharmacist for a medication review, can both organisations confirm they are discussing the same patient? The answer depends on whether the VCSE has been granted the system access to verify — and many have not.

Consent across four separate data controllers in one corridor

Consent becomes dramatically more complex when four separate data controllers occupy one building. The patient sees “the neighbourhood health team.” They do not see four independent data controllers, each processing their data under different legal bases, for different purposes, subject to different retention policies. A patient who consents to their GP sharing information with “the team” has not given valid consent under UK GDPR for their data to cross to a separate data controller. The NHS Transformation Directorate guidance on sharing information with the voluntary sector makes clear that specific arrangements are needed — but in a co-located setting where the boundary is invisible to the patient, the likelihood of those arrangements being properly operationalised is low.

Provenance broken across five incompatible clinical record systems

Provenance is challenged when clinical information passes verbally between staff employed by different organisations with different record-keeping standards. The community nurse documents in SystmOne. The mental health practitioner documents in Rio. The GP documents in EMIS. The pharmacist documents in their PMR system. The social prescriber may document in a CRM platform that none of the other organisations can access. When clinical information crosses from one system to another — if it crosses at all — the provenance chain is broken.

Clinical Intent gaps between constitutionally different mandates

Clinical Intent carries constitutional risk because the scope of what each organisation can and will do is defined by its constitutional purpose. A GP referring to the co-located mental health practitioner may expect a full assessment and treatment plan. The mental health Trust’s service specification may limit the practitioner to triage and onward referral. The gap between what the GP intends and what the Trust is constituted to deliver at neighbourhood level is a Clinical Intent failure — and it occurs because the organisations have different institutional mandates, not because of individual communication failure.

MVRT across independent governance hierarchies in the same building

Alert & Responsibility (MVRT) — the critical flow explored in the previous article — is hardest to enforce across constitutional boundaries precisely because the two organisations have different escalation pathways, different risk appetites, and different governance hierarchies. When responsibility transfers from the GP practice to the mental health Trust, the escalation pathway for a missed acceptance runs through the Trust’s governance structure, not the practice’s. The GP has no authority to escalate within the Trust. The Trust has no obligation to respond to the GP’s governance framework. The bilateral confirmation that MVRT requires must bridge two independent governance architectures — and no current infrastructure does this.

Service Routing constrained by constitutional scope and statutory pathways

Service Routing is complicated by constitutional scope. A patient presenting with a mental health concern that has a safeguarding dimension cannot simply be routed to the mental health practitioner in the next room. The safeguarding pathway may require local authority involvement — another constitutional domain entirely, governed by the Children Act 1989 or the Care Act 2014, with its own data sharing framework, its own professional roles (social workers with specific statutory duties), and its own governance structure. The neighbourhood centre’s internal routing cannot override the constitutional requirements of the safeguarding pathway, but the informality of co-location creates pressure to handle things locally rather than engage the formal cross-boundary process.

Outcome feedback loops that do not exist across constitutional boundaries

Outcome is structurally difficult when the originating and receiving organisations use different clinical systems with no interoperability. The GP who refers to the VCSE social prescribing service may never learn whether the patient attended, what was offered, or what the outcome was — because the VCSE’s recording system does not feed back into the GP clinical record. The feedback loop that should close the governance chain simply does not exist at most of these boundaries.

The Single Neighbourhood Provider contract adds a sixth constitutional layer

The Single Neighbourhood Provider contract, due to roll out from 2026, is designed to create a single accountable provider for each neighbourhood. The intention is to simplify commissioning and integrate delivery. But the constitutional reality is more complicated.

An SNP contract can be held by a GP federation, a primary care collaborative, a community Trust, an acute Trust, or a mental health Trust. The NHS Confederation’s analysis notes that the policy allows this to depend on “where local integration models prefer” — but the constitutional implications of who holds the contract are profound.

If a community Trust holds the SNP contract, the GP practices within the neighbourhood remain independent contractors. The Trust is accountable for neighbourhood outcomes, but it has no direct governance authority over the GP practices that deliver core general medical services. The boundary between the SNP holder and the GP practices is a constitutional boundary — employer versus independent contractor, NHS body versus private business — and the SNP contract sits on top of it without dissolving it.

If a GP federation holds the SNP contract, it may lack the clinical governance infrastructure that an NHS Trust has. It may not have a Clinical Safety Officer. It may not have established pathways for DCB 0129 compliance on digital systems it commissions. The federation is a corporate vehicle, not a clinical governance framework, and the constitutional gap between holding a contract and governing clinical safety across multiple organisations remains.

What is the constitutional governance gap in the SNP contract?

The SNP does not merge the five constitutional domains in a neighbourhood health centre into one. It adds a sixth layer — the contract holder — which has accountability for outcomes across organisations it does not employ, regulate, or govern. This is a constitutional arrangement that creates responsibility without authority, accountability without control. Without explicit boundary governance infrastructure, the SNP contract holder has a legal obligation to deliver integrated neighbourhood care and no mechanism to ensure that the seven governance flows function at every internal boundary.

The constitutional transition matrix: ten boundaries, ten different risk profiles

At Inference Clinical, our Seven Flows methodology includes a constitutional assessment dimension. We map the constitutional crossing type between every organisation pair in a boundary, because the governance risk is not the same at every crossing.

An NHS-to-NHS boundary (community Trust to mental health Trust) is constitutionally the simplest. Both organisations operate under the same broad legislative framework, both are CQC regulated, both employ staff on NHS terms. The governance architectures are similar even if the specific policies differ.

A primary care-to-VCSE boundary is constitutionally among the most complex. The GP practice is a regulated healthcare provider; the VCSE may not be. The practice has mandatory clinical governance requirements; the VCSE’s governance depends on its legal form. The practice uses NHS clinical systems; the VCSE may use an entirely separate platform. The data sharing legal basis is different. The professional accountability frameworks are different. Almost nothing aligns.

A crossing that involves an insurance or private payer adds commercial confidentiality requirements on top of clinical governance requirements. A crossing to or from community pharmacy involves a different regulator (GPhC rather than CQC) with different inspection standards and different enforcement powers.

The constitutional transition matrix is not symmetric. Referring from an NHS Trust to a GP practice creates different governance requirements than referring from a GP practice to an NHS Trust, because the direction of the crossing changes which organisation is the sender and which is the receiver — and therefore which governance framework applies to the act of releasing responsibility versus accepting it.

A neighbourhood health centre with five organisations does not have ten identical boundaries. It has ten constitutionally distinct boundaries, each with a different risk profile determined by the specific constitutional domains involved. Treating them as equivalent — applying the same governance framework to every internal crossing — is a structural error that the Seven Flows methodology is designed to prevent. See the full Constitutional Transition Matrix →

Four governance requirements before organisations co-locate in a neighbourhood health centre

The neighbourhood health implementation programme focuses on estates, digital, workforce, and finance as the four enablers. Constitutional governance is not among them. But it is the foundation on which all four depend.

Before organisations co-locate in a neighbourhood health centre, the constitutional dimension requires explicit attention in at least four areas.

First, data controller mapping. Every organisation in the building is a separate data controller. The data flows between them must be mapped, the legal bases identified, the Data Protection Impact Assessments completed, and the data sharing agreements signed — for every bilateral boundary, not as a single blanket arrangement that obscures the constitutional differences between crossings.

Second, regulatory alignment assessment. The organisations in the building are regulated by different bodies to different standards. Where clinical services cross from one regulatory domain to another — from CQC-regulated general practice to GPhC-regulated pharmacy, for instance — the standards gap must be identified and the governance arrangements must bridge it. Patients should not experience different standards of clinical governance depending on which organisation within the building happens to be providing their care at that moment.

Third, escalation pathway mapping. When something goes wrong at a boundary — a missed handover, an unacknowledged referral, a patient who falls between organisations — the escalation pathway must be pre-defined and tested. In a single organisation, the escalation runs up through line management. Across a constitutional boundary, there is no shared line management. The escalation must be agreed bilaterally, documented, and tested before the first patient walks through the door.

Fourth, clinical safety officer coordination. If the neighbourhood centre contains three or more organisations that each have (or should have) a Clinical Safety Officer, those CSOs need a coordination mechanism. A clinical safety incident at a boundary between two organisations will appear in both organisations’ hazard logs — or, more likely, in neither, because each organisation’s CSO scopes their hazard log to their own services. Boundary incidents need a boundary governance mechanism that sits across the constitutional domains, not within them.

Information Governance (IG) for co-located teams

Information Governance leads face the sharpest edge of constitutional complexity. Five separate data controllers sharing a building means five separate Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs), not one. It means bilateral Data Sharing Agreements (DSAs) for every organisational crossing — up to ten in a five-organisation centre — each identifying the specific legal basis under UK GDPR, the lawful basis for processing (Article 6 and, for health data, Article 9), the retention period, and the rights of the data subject. A blanket Information Sharing Agreement that treats the neighbourhood centre as a single entity is not legally compliant when the organisations within it are independent data controllers with different processing purposes. The Caldicott Guardian for each organisation must be identified. The Data Protection Officer (or equivalent) for each organisation must confirm that the sharing arrangements meet their organisation’s specific obligations. In practice, most co-located services begin sharing data informally — “we’re all in the same team” — months before the formal IG infrastructure catches up. By then, the constitutional boundaries have been breached repeatedly without documentation.

What the ICB must verify before neighbourhood co-location

The ICB, as commissioner and system steward, has a governance obligation to verify that constitutional readiness exists before neighbourhood co-location proceeds. At minimum, the ICB should require evidence that:

- All bilateral data sharing agreements are signed — not a single blanket ISA, but specific agreements covering each constitutional crossing with identified legal bases, retention policies, and DPIA outcomes.

- Regulatory gap analysis is complete — documenting where CQC, GPhC, and VCSE governance standards diverge, and what bridging arrangements are in place for services that cross regulatory domains.

- Cross-boundary escalation protocols are tested — not just documented, but rehearsed with named individuals in each organisation, with evidence that the escalation pathway works when invoked.

- CSO coordination is operational — a standing mechanism for Clinical Safety Officers across the co-located organisations to review boundary incidents, maintain a shared boundary hazard register, and report jointly to the neighbourhood governance board.

- The constitutional transition matrix is scored — every bilateral boundary mapped, risk-scored based on constitutional distance, and assigned a governance priority that reflects the true complexity of that crossing.

- The SNP contract holder’s governance authority is defined — explicit documentation of what governance powers the contract holder has (and does not have) over each co-located organisation, particularly where the holder is not the employer.

Private healthcare portfolios face identical constitutional crossing risk

Constitutional complexity is not unique to NHS neighbourhood centres. A private equity portfolio company that acquires a chain of GP practices, a physiotherapy provider, and a diagnostic imaging company has created three constitutionally distinct entities under common ownership — each with different CQC registrations, different clinical governance frameworks, and different regulatory obligations. The corporate parent has financial control but not necessarily clinical governance authority across the boundaries.

An insurer network that directs patients between a panel of independent providers — consultants, hospitals, diagnostic centres, rehabilitation services — creates constitutional crossings at every step of the patient pathway. The insurer adds a commercial governance layer (pre-authorisation, utilisation review, claims adjudication) that intersects with but does not replace the clinical governance at each provider.

The principle is the same: wherever organisations with different constitutional foundations interact around patient care, the boundary carries governance risk that is determined by the constitutional distance between them. The greater the constitutional distance, the more explicit the boundary governance must be.

The next article in the Architecting for Neighbourhood Health series introduces a practitioner framework for neighbourhood boundary governance — the Boundary Readiness model, a five-pillar framework for Legal, Clinical Safety, Process, People, and Technology readiness that replaces the traditional “People, Process, Technology” lens with one designed for the constitutional complexity of healthcare boundaries.

Architecting Neighbourhood Health Series

- What the Implementation Programme Is Missing

- Mapping the Seven Flows in a Neighbourhood Health Centre

- Clinical Responsibility Transfer — Why Handover Frameworks Don’t Cross Organisational Boundaries

- Constitutional Complexity — Five Organisations, Five Legal Frameworks, One Building (current)

- Boundary Readiness — Why “People, Process, Technology” Fails at Healthcare Boundaries

- The Legal Pillar — Data Sharing, Contractual Frameworks, and Constitutional Compliance

- The Clinical Safety Pillar — When the Hazard Sits Between Organisations

- The Process Pillar — Crossing Choreography and the Pre-Conditions Nobody Defines

- The People Pillar — Why Generic MDT Training Doesn’t Cross Organisational Boundaries

- The Technology Pillar — Why Interoperability That Doesn’t Preserve Governance Is Interoperability in Name Only

Inference Clinical’s Seven Flows Boundary Governance Audit includes constitutional transition mapping at every organisational boundary, with domain-specific risk scoring that reflects the true governance distance between co-located organisations. Constitutional crossing analysis reveals where regulatory, employment, and data controller differences create enhanced boundary risk. To understand the constitutional complexity within your neighbourhood, book a scoping call.