Key Takeaways

- Clinical safety frameworks stop at the organisational boundary — DCB 0129 and DCB 0160 are scoped to individual systems and individual organisations. Boundary hazards — the risks that arise when clinical information, responsibility, or workflow crosses between organisations — fall through the gap because nobody’s hazard log covers the space between.

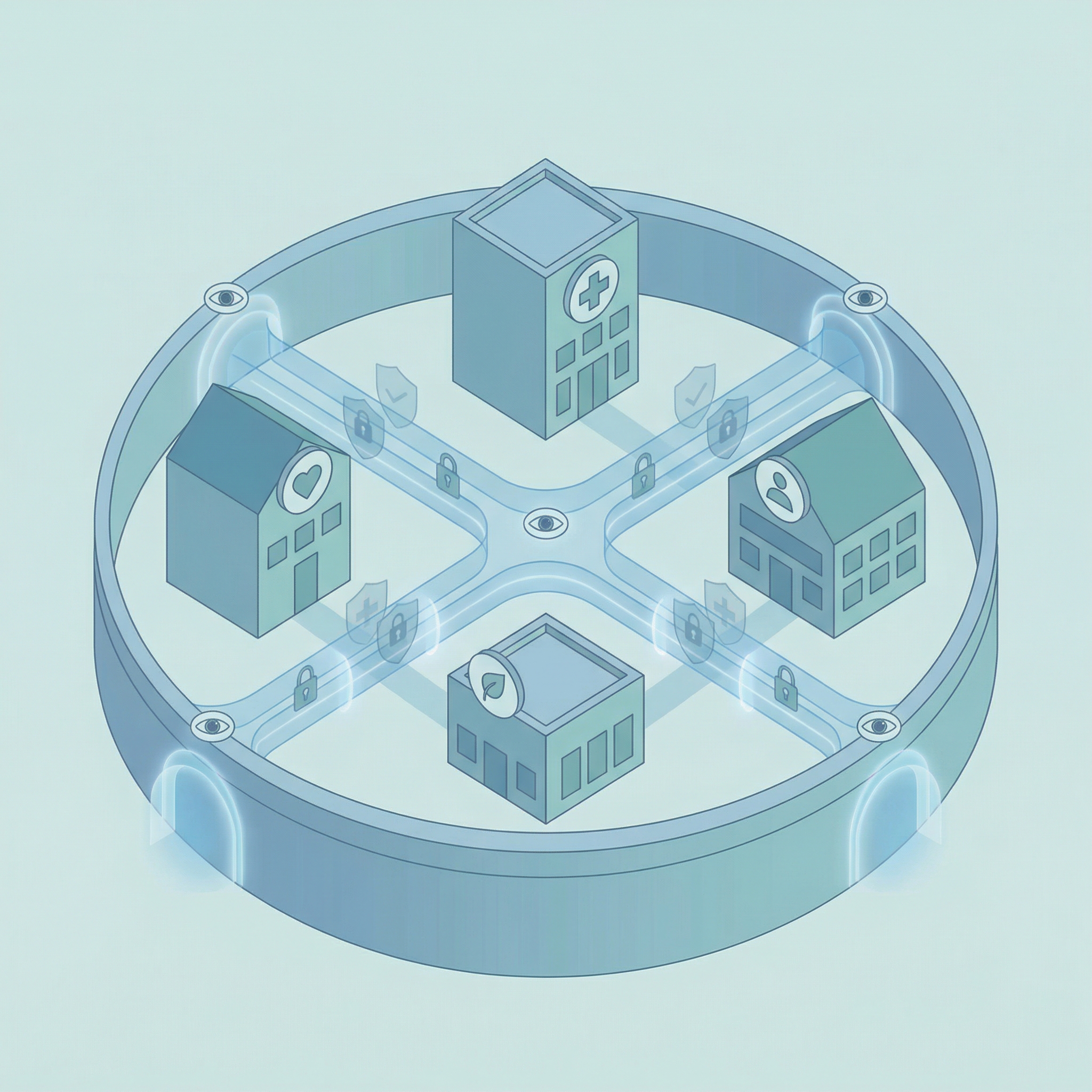

- Boundary hazards require a different taxonomy — Identity, Consent, Provenance, Clinical Intent, Alert & Responsibility, Service Routing, and Outcome hazards arise from governance failures at the interaction between systems, not from failures within them. The Seven Flows provide the hazard identification framework.

- CSO coordination is structurally absent — each organisation has its own Clinical Safety Officer whose scope ends at the organisational boundary. No standard requires CSOs to coordinate on boundary hazards, jointly review cross-boundary risks, or agree escalation pathways for boundary incidents.

- Cascade logic applies to boundary hazard scoring — an uncontrolled hazard in an upstream flow (such as Identity) increases the likelihood of every downstream hazard (such as MVRT failure). A boundary with well-functioning responsibility transfer but unassured patient identity is not a safe boundary.

- Clinical Safety depends on the Legal pillar being in place — without data sharing agreements and data controller mapping, the clinical safety assessment cannot determine what information is lawfully available at the boundary and therefore cannot assess the hazard of information being unavailable.

This is the seventh article in the Architecting for Neighbourhood Health series. The first article examined why the current governance conversation addresses committee structures but not boundary governance. The second introduced the Seven Flows that must function at every organisational crossing. The third went deep on clinical responsibility transfer and the MVRT principle. The fourth examined constitutional complexity — what happens when fundamentally different types of organisation share a building and a patient population. The fifth introduced the Boundary Readiness model that replaces People, Process, Technology with five pillars assessed in dependency order at every bilateral boundary. The sixth examined the Legal pillar — data sharing agreements, contractual frameworks, and constitutional compliance.

The Clinical Safety pillar answers a different question from the Legal pillar. Legal asks may this crossing happen. Clinical Safety asks what goes wrong when this crossing fails — and what controls exist to prevent, detect, or mitigate that failure.

Within a single NHS organisation, clinical safety is a mature discipline. Hazard logs capture risks. Incident reporting systems feed into the Learn from Patient Safety Events (LFPSE) service. The Patient Safety Incident Response Framework provides a structured approach to learning from incidents. Clinical governance committees meet monthly. Risk registers are maintained and reviewed. The CQC’s Well-Led framework assesses whether the governance architecture is functioning.

All of this stops at the organisational boundary.

What is a clinical boundary hazard?

A clinical boundary hazard is a patient safety risk that arises at the interface between two organisations — such as a referral lost in transmission, clinical information arriving without the context needed to interpret it safely, or a responsibility transfer that neither organisation has explicitly confirmed. Boundary hazards typically fall outside the scope of individual DCB 0129/0160 hazard logs because they originate in the interaction between organisations, not within either one.

When a clinical safety incident occurs between two organisations — a referral that was sent but never acknowledged, a discharge summary that arrived without the information the GP needed, a responsibility transfer that both organisations assumed the other had accepted — the incident does not sit cleanly within either organisation’s clinical governance framework. It sits in the space between them. And that space, in most neighbourhood health configurations, has no hazard log, no Clinical Safety Officer, no incident reporting pathway, and no governance committee.

The scope problem: DCB 0129 and DCB 0160

The NHS’s clinical safety standards for digital health are DCB 0129 (for manufacturers of health IT systems) and DCB 0160 (for healthcare organisations deploying and using those systems). Both are mandated under Section 250 of the Health and Social Care Act 2012. Both require the appointment of a Clinical Safety Officer — a registered clinician with appropriate training in clinical risk management. Both require hazard logs, clinical safety case reports, and clinical risk management plans. NHS England is currently reviewing both standards to ensure they remain practical and aligned with current technology.

These standards are essential. They are also scoped to single organisations. DCB 0160 requires a healthcare organisation to assess the clinical risks of deploying a health IT system within that organisation. It does not require the organisation to assess the clinical risks that arise at the boundary between that organisation and another organisation that uses a different system, a different clinical workflow, and a different governance framework.

Consider a neighbourhood health centre where the GP practice uses EMIS, the community Trust uses SystmOne, the mental health Trust uses Rio, and the community pharmacy uses its own PMR system. Each organisation’s CSO may have completed a hazard log for their own system. Each hazard log will capture risks like “clinician fails to see an alert” or “system displays incorrect medication” — hazards within the system and within the organisation. What none of those hazard logs will capture is the hazard that arises when clinical information crosses from one system to another: the referral sent from EMIS that arrives in SystmOne without the clinical context the receiving clinician needs, the discharge summary generated in the Trust’s PAS that sits in the GP’s workflow queue for days before anyone reads it, the medication change made by the pharmacist in the PMR that never reaches the GP record at all.

These are boundary hazards. They do not belong in any single organisation’s hazard log because they do not originate within any single organisation. They originate in the interaction between organisations — in the Seven Flows that the second article in this series described. And because DCB 0129 and DCB 0160 are scoped to individual systems and individual organisations, boundary hazards fall through the gap.

The CSO coordination problem

Both DCB 0129 and DCB 0160 require the appointment of a Clinical Safety Officer. The CSO must be a registered clinician — a doctor, nurse, pharmacist, or other regulated healthcare professional — with training in clinical risk management. The CSO oversees the hazard log, approves the clinical safety case report, and ensures that clinical risk management activities are integrated into the organisation’s processes.

In a neighbourhood health centre with five organisations, there could be up to five CSOs — one per organisation. In practice, the number may be lower. GP practices are not always required to appoint a CSO (the requirement depends on whether they deploy health IT systems that fall within scope of DCB 0160). VCSE organisations rarely have CSOs. Community pharmacies may share a CSO with a larger chain. But the organisations that do have CSOs — the community Trust, the mental health Trust, and potentially the GP practice or federation — have CSOs whose scope is defined by their own organisation’s boundaries.

The community Trust’s CSO manages the hazard log for systems deployed within the community Trust. The mental health Trust’s CSO manages the hazard log for systems deployed within the mental health Trust. Neither CSO’s scope extends to the boundary between the two Trusts. Neither hazard log captures the risk that arises when a community nurse refers a patient to the co-located mental health practitioner and the referral crosses from SystmOne to Rio without the clinical intent being preserved.

This is not a failure of individual CSOs. It is a structural gap in Clinical Safety Officer collaboration. The standards require a CSO per organisation. They do not require a CSO for the boundary. The standards require a hazard log per system deployment. They do not require a hazard log for the interaction between systems across organisational boundaries. There is no mandated cross-boundary safety group, no requirement for joint hazard workshops between co-located CSOs, and no template for a shared boundary hazard log. The clinical safety architecture is designed for nodes. The hazards in a neighbourhood health centre increasingly live at the edges.

Boundary hazards: a different taxonomy

Within an organisation, clinical safety hazards tend to fall into established categories: system unavailability, incorrect data display, alert fatigue, user interface design issues, data integrity failures. These are well understood, and the hazard identification methodologies described in DCB 0129 — Functional Failure Analysis, HAZID, SWIFT — are designed to find them.

Boundary hazards are different in character. They arise not from system failures but from governance failures at the interaction between systems, organisations, and clinical workflows. At Inference Clinical, our Seven Flows methodology identifies boundary hazards across each of the seven governance dimensions. These map to a different taxonomy from traditional digital clinical safety.

Identity hazards arise when the organisations on either side of a boundary cannot reliably confirm they are discussing the same patient. This sounds improbable until you consider the VCSE organisation that uses a CRM platform without NHS number integration, or the community pharmacist verifying identity from a prescription rather than a clinical system.

Consent hazards arise when clinical information crosses a boundary without the patient’s informed understanding that it is crossing to a different data controller — the co-location problem described in the sixth article. The clinical safety dimension is not just the data protection breach but the clinical consequence: if consent is subsequently challenged and revoked, the receiving clinician may lose access to information they have already used to make a clinical decision.

Provenance hazards arise when clinical information arrives at the receiving organisation without the context needed to interpret it safely. A test result without the requesting clinician’s rationale. A referral letter without the medication list. A verbal handover in a corridor that generates no auditable record. The LFPSE taxonomy captures incidents related to “information/communication” failures — but the structural cause at a boundary is the loss of provenance as information crosses from one governance domain to another.

Clinical Intent hazards arise when the receiving organisation misinterprets or cannot determine what the sending organisation expected to happen. The GP refers a patient to the co-located mental health practitioner expecting a full assessment. The Trust’s service specification limits the practitioner to triage. The gap between the GP’s clinical intent and the service’s scope creates a hazard — the patient believes they are being assessed, the GP believes assessment is underway, but the practitioner can only triage and refer onwards. Clinical Intent hazards are particularly dangerous because they are invisible until the patient falls through the gap.

Alert and Responsibility hazards — the MVRT failures described in the third article — are the most critical boundary hazard category. See our deep dive on MVRT failures. A patient whose clinical responsibility has been released by one organisation but not accepted by another is a patient with no named responsible clinician. The third article documented the 90-hour gap: hospital discharges on Friday at 16:47, the discharge summary arrives via MESH, sits in the GP’s workflow queue over the weekend, and the GP reviews it on Tuesday morning. For 90 hours, the patient’s clinical responsibility is in transit. If their condition deteriorates during that window, no organisation has explicitly accepted responsibility for responding.

Service Routing hazards arise when patients are directed to the wrong service — or the right service at the wrong time, or the right service without the pre-conditions that service needs before it can act. In a co-located setting where clinicians can “just walk next door,” routing bypasses the structured pathways that exist for good reason: to ensure the receiving service has the information, capacity, and governance authority to accept the patient.

Outcome hazards arise when the originating organisation never learns what happened after the boundary crossing. The GP refers to the mental health practitioner and receives no outcome communication. Did the patient attend? Were they assessed? Were they treated? Were they referred onwards? Without outcome data flowing back across the boundary, the GP cannot update the patient’s care plan, cannot identify deterioration, and cannot close the clinical loop. The boundary becomes a one-way door.

The hazard log gap

Each of these boundary hazard categories requires systematic identification, assessment, and mitigation — the same rigorous process that DCB 0129 and DCB 0160 require for system-level hazards. But there is no standard that requires a boundary hazard log. There is no standard that requires boundary hazards to be assessed for severity and likelihood. There is no standard that requires controls to be identified and their effectiveness monitored.

The result is predictable. Within each organisation, the hazard log captures risks to an appropriate level of rigour. Between organisations, the hazards are either unidentified (because nobody’s scope includes the boundary), identified but undocumented (because there is no hazard log for the boundary to capture them), or documented in one organisation’s hazard log but without the participation of the other organisation that co-creates the risk.

A boundary hazard cannot be meaningfully assessed by one organisation alone. The community Trust’s CSO can identify that “referral from GP may arrive without required clinical information” is a hazard. But the severity and likelihood of that hazard depends on the GP practice’s referral processes, their system configuration, and their clinicians’ behaviour — none of which the Trust’s CSO has visibility of or authority over. Conversely, the GP practice may identify that “discharge summary from Trust may be delayed” is a hazard, but the likelihood depends on the Trust’s discharge processes, their system’s MESH configuration, and their ward staff’s documentation practices.

Boundary hazards are inherently bilateral. They require bilateral assessment. And bilateral assessment requires a governance mechanism that sits across the organisations — which, in most neighbourhood health configurations, does not exist.

Example: Documenting a boundary hazard in a DCB 0160 safety case

A boundary hazard entry follows the same Hazard → Cause → Effect → Control structure used in DCB 0129/0160 hazard logs, but requires bilateral input from both organisations:

- Hazard: GP referral to co-located mental health service arrives without medication history

- Cause: EMIS referral template does not auto-populate current medications; SystmOne has no access to GP prescribing record; no bilateral protocol requires medication list in referral

- Effect: Mental health practitioner prescribes without knowledge of current medications — risk of drug interaction, contraindication, or therapeutic duplication (Severity: Major; Likelihood: Probable → Risk: Unacceptable)

- Control: Bilateral referral protocol requiring structured medication summary; system-level check at receiving end confirming medication field is populated before appointment is booked; escalation to referring GP if medication data is absent

This hazard cannot be meaningfully assessed by the Trust’s CSO alone — the cause originates in the GP practice’s system and workflow. Nor can the GP practice’s CSO assess the effect — the prescribing risk materialises in the Trust’s service. The hazard is bilateral. The assessment must be bilateral. The control requires both organisations to act.

Clinical incident reporting at boundaries

The NHS’s patient safety incident reporting infrastructure has undergone significant modernisation. The LFPSE service, which replaced the National Reporting and Learning System in 2024, now receives over 800,000 patient safety event records per quarter from NHS providers. The Patient Safety Incident Response Framework (PSIRF) has replaced the Serious Incident Framework, promoting a systems-based approach to learning rather than individual blame.

Both LFPSE and PSIRF represent genuine advances. Both remain, structurally, organisation-centric. A patient safety incident is recorded by the organisation whose staff identify it — which, for boundary incidents, is typically the receiving organisation that discovers the failure. The community Trust clinician who finds that a GP referral arrived without essential clinical information records the incident in the Trust’s LRMS. The GP practice that discovers a discharge summary was delayed records it in the practice’s incident reporting system.

In neither case does the reporting automatically trigger a cross-boundary investigation. The Trust’s PSIRF process investigates within the Trust’s governance framework. The GP practice’s process investigates within the practice’s governance framework. The boundary itself — the interaction that generated the incident — is not investigated as a system, because no single organisation’s governance framework encompasses it.

PSIRF explicitly advocates a “systems-based approach” — recognising that patient safety is an emergent property of the healthcare system, not a characteristic of individual components. This is precisely the right principle. But the system that PSIRF investigates is typically bounded by the organisation. The system that generates boundary incidents spans multiple organisations — and the investigation framework has not yet caught up with that reality.

What the Clinical Safety pillar requires

The Clinical Safety pillar of Boundary Readiness does not replace DCB 0129, DCB 0160, or PSIRF. It extends their principles to the space between organisations — the space where co-located care creates hazards that no single organisation’s clinical safety framework is designed to capture.

At Inference Clinical, the Clinical Safety pillar assessment covers five domains at every bilateral boundary.

First, boundary hazard identification — systematic identification of clinical safety hazards at the boundary, using the Seven Flows as the hazard identification framework. Each flow is assessed for failure modes at the specific boundary, with the constitutional crossing type (identified in Article 4) informing the risk profile. An NHS-to-NHS boundary generates different hazards from an NHS-to-VCSE boundary. The hazard identification is bilateral — both organisations participate, because boundary hazards cannot be identified from one side alone.

Second, boundary hazard assessment — each identified hazard assessed for severity (what happens to the patient if this hazard materialises) and likelihood (how probable is it, given the current governance architecture at this boundary). The assessment uses the same risk matrix methodology as DCB 0129 and DCB 0160, extended to boundary-specific contexts. Cascade logic applies: a hazard in an upstream flow (such as Identity or Consent) that is uncontrolled will increase the likelihood of downstream hazards (such as Alert & Responsibility or Outcome). A boundary where Identity is unassured has a structurally higher likelihood of MVRT failure.

Third, CSO coordination assessment — determining whether the CSOs (or equivalent clinical safety leads) of the co-located organisations have a defined coordination mechanism. Do they meet? How often? Is there a shared understanding of boundary hazards? Is there an agreed escalation pathway for boundary incidents? Have they jointly reviewed the hazards that sit between their organisations? The assessment does not require a single CSO for the neighbourhood — the constitutional independence of each organisation means each retains its own CSO. But it does require that those CSOs have a structured way to collaborate on boundary risks.

Fourth, boundary incident pathway assessment — verifying that a defined pathway exists for reporting, investigating, and learning from incidents that occur at the boundary rather than within either organisation. This includes determining which organisation leads the investigation (or whether it is jointly led), how both organisations’ PSIRF processes interact, and how learning is shared back across the boundary so that both organisations can update their controls.

Fifth, MVRT infrastructure assessment — the specific assessment of whether responsibility transfer across the boundary meets the Minimum Viable Responsibility Transfer principle described in the third article. Can the system identify patients whose responsibility is in transit? Is bilateral confirmation required before a transfer is marked as complete? Is there a clinically safe escalation pathway when acknowledgement is not received? Does the infrastructure produce the audit trail that CSOs need? MVRT failure is the single highest-severity boundary hazard because it directly creates the condition of an unowned patient.

The cascade principle in clinical safety

The second article in this series introduced the cascade logic of the Seven Flows: upstream failures cap the effectiveness of downstream flows. This cascade principle has direct implications for clinical safety assessment at boundaries.

If the Identity flow is unassured at a boundary — if the organisations cannot reliably confirm they are discussing the same patient — then every downstream hazard has its likelihood increased. A Consent hazard is more likely if the patient’s identity hasn’t been confirmed. A Provenance hazard is more likely if clinical records may be attributed to the wrong patient. An MVRT failure is more likely if the bilateral confirmation is applied to the wrong patient record.

The Clinical Safety pillar assessment applies cascade adjustment to boundary hazard scores. A hazard in a downstream flow cannot have a lower likelihood score than the worst uncontrolled hazard in an upstream flow on which it depends. This produces adjusted risk scores that reflect the structural reality: a boundary with a well-functioning MVRT process but an unassured Identity flow is not a safe boundary, because the MVRT process is confirming responsibility transfer for a patient whose identity may not be verified.

This cascade-adjusted scoring was illustrated in the sixth diagram of this series — the sample boundary scorecard showing how a raw score of 2 on Service Routing adjusts down to 1 when Clinical Intent (on which Service Routing depends) is uncontrolled. The Clinical Safety pillar makes these dependencies explicit and auditable.

The private sector dimension

Private healthcare faces the same Clinical Safety pillar requirements with fewer structural supports. NHS organisations at least have DCB 0160, PSIRF, LFPSE, and the CQC’s Well-Led framework. Private healthcare organisations — particularly those outside the scope of CQC registration — may have no mandated clinical safety framework at all.

An insurer network directing patients between independent providers creates boundary hazards at every step. The pre-authorisation decision that delays a referral until clinical urgency escalates. The change of provider mid-pathway that requires clinical records to transfer between organisations with no shared system. The rehabilitation programme delivered by a provider who never receives the surgical notes. Each of these is a boundary hazard. None of them sit within a mandated clinical safety assessment framework.

The principle is the same as in the NHS: wherever patient care crosses an organisational boundary, clinical safety hazards arise at the crossing. Those hazards must be identified, assessed, and controlled with the same rigour applied to hazards within organisations. The absence of a mandated standard does not mean the absence of the hazard — it means the hazard is unmanaged.

Clinical Safety builds on Legal

The Boundary Readiness model’s dependency ordering places Clinical Safety as the second pillar, after Legal. This is not arbitrary. The Clinical Safety assessment depends on the Legal pillar being in place.

If the data sharing agreements between organisations have not been established, the clinical safety assessment cannot determine what information is lawfully available at the boundary — and therefore cannot assess the hazard of information being unavailable. If the data controller mapping has not been completed, the CSO coordination mechanism cannot be properly defined because it is unclear which organisations are independent controllers with their own clinical safety obligations. If the contractual framework is silent on cross-boundary obligations, the Clinical Safety pillar cannot assess whether controls that depend on contractual compliance will actually be enforced.

Legal provides the architecture. Clinical Safety identifies what fails within that architecture. Process — the third pillar, examined in the next article — defines what must be true before each specific crossing can safely occur. The dependency is not theoretical. It is structural. A Clinical Safety assessment conducted without the Legal pillar in place will miss hazards that arise from legal gaps, misidentify hazards that the legal architecture actually resolves, and propose controls that the contractual framework has no mechanism to enforce.

Safety between, not just within

The NHS’s clinical safety infrastructure is strong and improving. The LFPSE service captures over three million patient safety events per year. The PSIRF framework promotes systems-based learning. The DCB standards provide rigorous methodology for digital clinical risk management. NHS England’s ongoing review of DCB 0129 and DCB 0160 demonstrates a commitment to keeping the standards current.

The gap is not in the strength of these frameworks. The gap is in their scope. They are designed for safety within organisations, within systems, within governance boundaries. Neighbourhood health creates care that routinely crosses those boundaries — multiple times per patient, multiple times per day, across organisations with different systems, different governance frameworks, and different CSOs.

The Clinical Safety pillar of Boundary Readiness extends the principles that already work within organisations to the space between them. Boundary hazard logs. Bilateral hazard assessment. CSO coordination mechanisms. Cross-boundary incident pathways. MVRT infrastructure assessment. Cascade-adjusted risk scoring. None of this replaces what exists. All of it fills the gap that co-location creates and that the current standards do not yet cover.

If Legal asks may this crossing happen, Clinical Safety asks what happens to the patient when it goes wrong. In a neighbourhood health centre with five organisations and ten bilateral boundaries, the answer to that question must be documented, assessed, and governed — not assumed, not hoped, and not left to the space between hazard logs that nobody owns.

The next article examines the Process pillar: the specific pre-conditions that must be confirmed before each type of boundary crossing can validly occur — why a GP-to-cardiologist referral has different requirements from a GP-to-safeguarding referral, and what “crossing choreography” looks like when it is properly defined.

Architecting Neighbourhood Health Series

- What the Implementation Programme Is Missing

- Mapping the Seven Flows in a Neighbourhood Health Centre

- Clinical Responsibility Transfer — Why Handover Frameworks Don’t Cross Organisational Boundaries

- Constitutional Complexity — Five Organisations, Five Legal Frameworks, One Building

- Boundary Readiness — Why “People, Process, Technology” Fails at Healthcare Boundaries

- The Legal Pillar — Data Sharing, Contractual Frameworks, and Constitutional Compliance

- The Clinical Safety Pillar — When the Hazard Sits Between Organisations (current)

- The Process Pillar — Crossing Choreography and the Pre-Conditions Nobody Defines

- The People Pillar — Why Generic MDT Training Doesn’t Cross Organisational Boundaries

- The Technology Pillar — Why Interoperability That Doesn’t Preserve Governance Is Interoperability in Name Only

Inference Clinical’s Seven Flows Boundary Governance Audit assesses the Clinical Safety pillar at every bilateral boundary — boundary hazard identification across all seven flows, cascade-adjusted severity scoring, CSO coordination assessment, and MVRT infrastructure compliance. To understand the clinical safety architecture of your neighbourhood boundaries, book a scoping call.