Key Takeaways

- SBAR and existing handover protocols standardise communication content but do not address the transfer of legal responsibility between independent organisations — every corridor conversation in a neighbourhood health centre is an undocumented inter-organisational handover.

- Minimum Viable Responsibility Transfer (MVRT) is the principle that clinical responsibility transfer must be explicit, bilateral, confirmed, and infrastructure-enforced — the standard every other safety-critical industry achieved decades ago.

- Neighbourhood health centres multiply inter-organisational handovers exponentially while making them less formal. Five co-located organisations processing hundreds of multi-disciplinary interactions per day create MVRT events that no current governance framework captures.

- MVRT has five requirements: explicit bilateral declaration, infrastructure enforcement, clinically safe escalation, unowned patient identification, and auditable governance artefacts.

- Cascading failure logic means an MVRT failure doesn’t just affect Alert & Responsibility — it structurally breaks Service Routing and the Outcome flow, making boundary-level safety measurement impossible.

This is the third article in the Architecting for Neighbourhood Health series. The first article examined why the governance conversation about neighbourhood health addresses committee structures but not boundary governance. The second introduced the Seven Flows — the seven dimensions that must function at every organisational crossing. This article goes deep on the fifth and most critical flow: Alert & Responsibility, and the principle we call Minimum Viable Responsibility Transfer.

The National Patient Safety Agency defined clinical handover as “the transfer of professional responsibility and accountability for some or all aspects of care for a patient, or group of patients, to another person or professional group on a temporary or permanent basis.” This definition has shaped twenty years of handover improvement in the NHS — SBAR protocols, standardised shift handovers, safety huddles, surgical checklists.

All of it was designed for handovers within organisations.

A major research programme funded by the National Institute for Health Research examined clinical handover across the emergency care pathway and concluded that “further research is required in understanding handover across organisational boundaries,” noting that “different organisations have different goals and exhibit different local cultures and behaviours” and that handover across organisations requires “the alignment of different individual and organisational motivations and backgrounds.” The study found that communication failures contribute to approximately two out of three serious preventable adverse events in hospitals — within a single organisation. At the boundary between organisations, the failure rate is unmeasured because no framework exists to capture it.

The neighbourhood health model is about to massively increase the volume of inter-organisational handovers while simultaneously making them less formal. This is the most dangerous structural characteristic of co-located care, and the current implementation programme does not address it.

What SBAR was designed for — and what it cannot do at the corridor boundary

SBAR — Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation — is the most widely adopted handover protocol in the NHS. It was developed for structured communication between clinicians, typically within the same organisation. It works well for what it was designed to do: standardise the content of a verbal handover so that critical information is communicated in a predictable order.

But SBAR assumes a shared context. Both parties work within the same clinical governance framework. Both have access to the same clinical systems. Both are employed by the same organisation with the same policies, the same risk appetite, and the same escalation pathways. The protocol standardises communication. It does not address the transfer of legal responsibility between independent organisations.

When a GP in a neighbourhood health centre asks the co-located community mental health nurse to assess a patient, the clinical communication might follow SBAR perfectly. The GP states the situation, provides the background, offers their assessment, and makes a recommendation. But SBAR does not answer the questions that matter at an organisational boundary:

Has the mental health nurse formally accepted clinical responsibility for this patient? If something goes wrong between the GP’s request and the nurse’s assessment, who is accountable? If the nurse assesses the patient and identifies a safeguarding concern, does the nurse escalate through their own Trust’s safeguarding pathway or through the neighbourhood centre’s? If the nurse is unable to see the patient today and the patient deteriorates overnight, whose governance system captures the delay?

SBAR addresses the content of communication. It does not address the transfer of accountability. In a neighbourhood health centre, where every multi-disciplinary interaction crosses an organisational boundary, this distinction is the difference between governed care and an assumption of safety.

Why SBAR fails at the organisational boundary

The gap between SBAR and what neighbourhood health boundaries require is structural, not incremental. SBAR was designed for a world where both clinicians share the same governance framework. MVRT is designed for the world neighbourhood health centres actually create.

| Dimension | SBAR (Internal Handover) | MVRT (Cross-Boundary Transfer) |

|---|---|---|

| Scope | Single organisation | Multi-organisation boundary |

| Governance context | Shared framework, shared systems | Separate CQC registrations, separate data controllers |

| Responsibility transfer | Implied by communication | Explicit bilateral confirmation required |

| Acceptance | Assumed from receipt | Actively confirmed, infrastructure-enforced |

| Escalation | Relies on individual follow-up | Clinically timed, system-enforced escalation |

| Unowned patient risk | Mitigated by shared governance | Structurally identified and flagged in real time |

| Audit trail | Within single EPR | Cross-organisational, statutory-traceable governance artefact |

The principle aviation, maritime, and nuclear solved decades ago

At Inference Clinical, we formalised the principle that sits beneath this problem. We call it Minimum Viable Responsibility Transfer — MVRT. It is the normative control for the fifth of our Seven Flows — Alert & Responsibility — and it derives from a principle that every other safety-critical industry has built into its infrastructure.

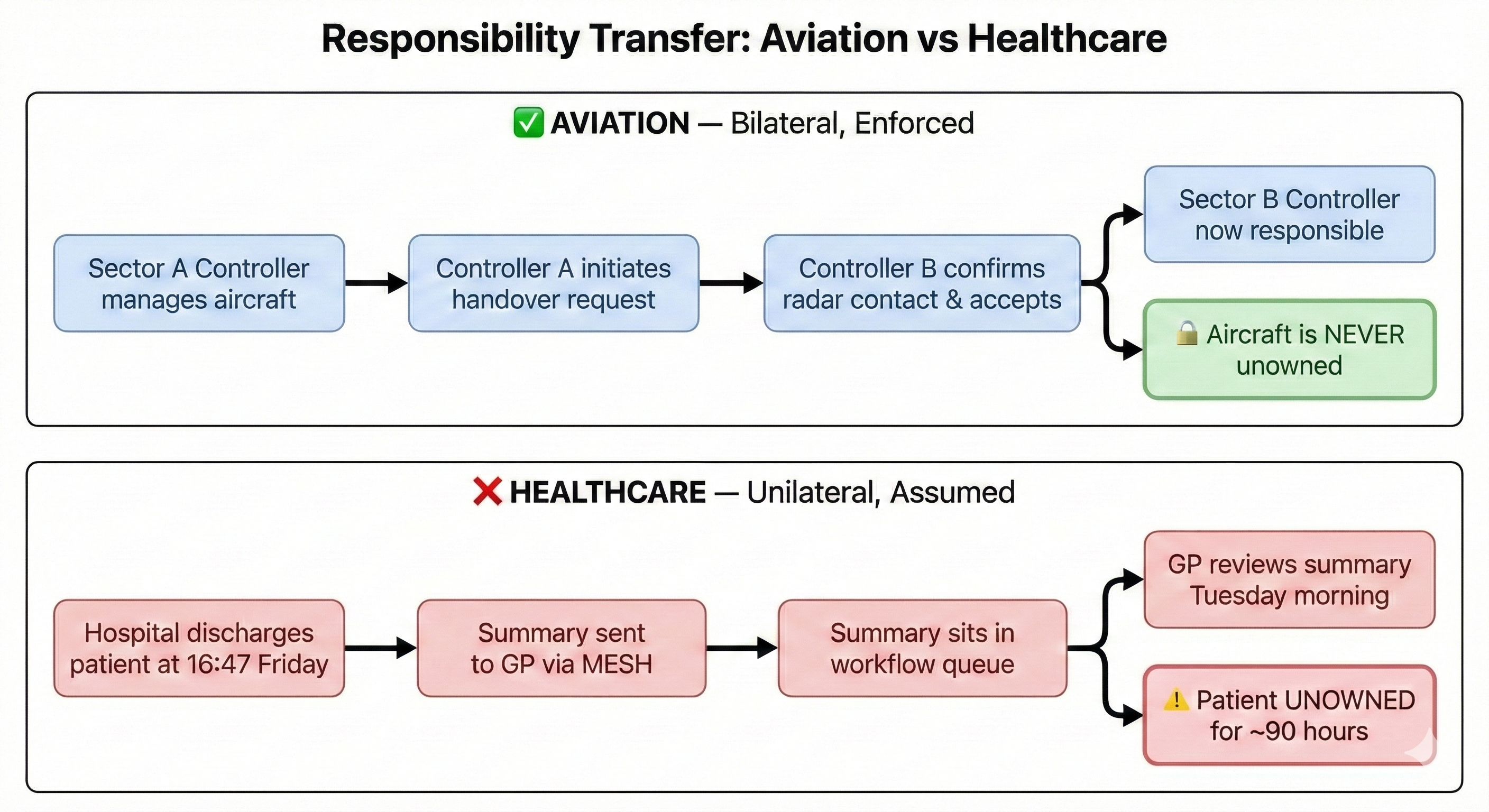

In aviation, an aircraft transiting from one air traffic control sector to another cannot complete the handover until the receiving controller electronically verifies and accepts responsibility. The infrastructure structurally prevents the existence of an unowned aircraft. There is no interval — however brief — where no one is responsible.

In maritime operations, a vessel transiting between port authorities follows a defined protocol where the receiving authority acknowledges the vessel’s entry, confirms its identity, and accepts monitoring responsibility. The handover is bilateral, logged, and time-stamped.

In nuclear power generation, shift handovers require the incoming team to physically confirm their understanding of plant status before the outgoing team can leave. The handover cannot complete unilaterally.

The common principle across all of these is bilateral confirmation: the transfer is not complete until both parties have confirmed it. The sending party cannot declare the transfer done. The receiving party must actively accept. And the infrastructure enforces this — it is not a process that depends on people remembering to follow it.

Healthcare routinely violates this principle. A hospital can mark a patient as discharged before the GP has acknowledged receipt of the discharge summary. A referral can enter a booking system without the receiving consultant confirming they have reviewed it. A clinical responsibility transfer can happen through a corridor conversation with no record that the receiving clinician has accepted the responsibility being transferred.

What is Minimum Viable Responsibility Transfer (MVRT)?

MVRT codifies the minimum that must be true for a clinical responsibility transfer to be considered governed: explicit (both parties know a transfer is occurring), bilateral (the receiving party actively accepts), confirmed (acceptance is recorded with timestamp and identity), and infrastructure-enforced (the system prevents unilateral completion). In our scoring model, a boundary that cannot demonstrate MVRT cannot achieve “Managed” status on Alert & Responsibility — and because cascading failure logic links Alert & Responsibility to Outcome, an MVRT failure structurally caps the Outcome score as well.

Why the neighbourhood health centre multiplies MVRT failures

Traditional NHS referral pathways have a limited number of inter-organisational handovers. A GP refers to a hospital. The hospital discharges back to the GP. There may be intermediate steps — a diagnostic provider, a community service — but each interaction is a discrete, identifiable event that passes through some form of structured channel: e-RS, MESH, a referral management system.

A neighbourhood health centre fundamentally changes this arithmetic. Five co-located organisations — a GP practice, an NHS community Trust, a mental health Trust, a community pharmacy, a VCSE organisation — create up to ten bilateral boundaries. But the number of boundaries is not the critical variable. The critical variable is the volume of handovers per boundary.

In a traditional model, the GP might make a handful of referrals to community services per day. In a co-located model, the GP may interact with the community nurse, the mental health practitioner, the pharmacist, and the social prescriber multiple times in a single morning — each interaction a potential responsibility transfer across an organisational boundary. The NHS England guidelines envision neighbourhood multidisciplinary teams as the core delivery mechanism. Multi-disciplinary team working, by definition, involves constant clinical interaction across organisational lines. Each interaction is a potential MVRT event.

The informality of co-location makes this worse. In a formal referral pathway, the referral itself — however imperfect — creates a record. A timestamp. A sender. A recipient. A documented clinical reason. The referral may not satisfy MVRT (the receiving organisation may not confirm acceptance), but at least the existence of the handover is captured.

In a corridor conversation, nothing is captured. The GP asks the mental health practitioner to see a patient. The mental health practitioner agrees. No record is created in either organisation’s clinical system. No timestamp documents when responsibility transferred. No confirmation exists that the mental health practitioner understood and accepted what they were being asked to do. If the mental health practitioner forgets — because they were interrupted, because they had competing priorities, because the verbal request was ambiguous — the patient exists in a governance vacuum. Nobody’s patient.

The MDDUS — the UK medical defence organisation — advises clinicians to “check the handover recipient understands the information given and accepts responsibility for the patient’s care.” This is correct individual practice guidance. But it places the governance obligation on the individual clinician rather than on the infrastructure. In a neighbourhood centre processing hundreds of multi-disciplinary interactions per day, relying on individual clinicians to ensure bilateral confirmation at every handover is not governance. It is hope.

The five requirements of MVRT at a neighbourhood boundary

MVRT is not a technology product. It is a governance principle that infrastructure must enforce. Our methodology assesses every boundary against five specific requirements:

1. Explicit bilateral declaration at the corridor boundary

The sending organisation explicitly releases responsibility. The receiving organisation explicitly accepts it. Neither party can unilaterally declare the transfer complete. In our scoring framework, this is the threshold for “Managed” status on Alert & Responsibility. Without bilateral declaration, a boundary cannot achieve it — regardless of how well every other flow functions.

2. Infrastructure enforcement in the coordination platform

The transfer cannot complete without bilateral acknowledgement. This is a system design requirement, not a process requirement. A discharge that can be marked “complete” before the GP has acknowledged receipt is a system that permits MVRT failure by design. A neighbourhood centre coordination platform that allows the GP to assign a task to the mental health team without requiring confirmed acceptance is infrastructure that enables governance vacuums. Our technology assessment evaluates whether neighbourhood coordination platforms enforce or undermine bilateral confirmation.

3. Clinically safe escalation when the corridor goes quiet

If acknowledgement is not received within a defined timeframe, the system escalates. The timeframe is clinically determined — hours for acute care, days for routine referrals — and the escalation pathway is pre-defined and tested. In a neighbourhood centre, where many interactions are same-day, the escalation timeframes may be measured in minutes, not hours.

4. Unowned patient identification across the building

At any point, the system can identify patients who are in transit between organisations with no named responsible clinician. These patients are flagged, visible, and actively managed. In a neighbourhood centre, this means the coordination platform must be able to answer the question: “Right now, which patients have been referred from one organisation to another within this centre and have not yet been confirmed as accepted?”

5. Auditable governance artefact for the Clinical Safety Officer

Every MVRT event is logged, time-stamped, and traceable. The log feeds into the clinical safety hazard log. MVRT failures are treated as safety events, not administrative inconveniences. This creates the evidence base that CSOs need: documented, boundary-specific, statutory-traceable records of how responsibility transferred at each organisational crossing.

What the neighbourhood coordination platform must enforce

The digital coordination platform that connects organisations within a neighbourhood health centre is the infrastructure layer where MVRT either works or doesn’t. At minimum, the platform must:

- Prevent unilateral completion — a task assigned to another organisation cannot be marked as “handed over” until the receiving organisation confirms acceptance within the platform.

- Track real-time responsibility status — for every patient discussed across organisational lines, the platform knows which organisation currently holds responsibility and when the last status change occurred.

- Escalate on timeout — if a responsibility transfer is initiated and not acknowledged within a configured timeframe, the platform escalates to a named senior clinician in both organisations.

- Surface the unowned list — at any moment, the platform can generate a list of patients currently in transit between organisations with no confirmed responsible clinician.

- Log every transfer as a governance event — each MVRT interaction is recorded with timestamp, sending clinician, receiving clinician, clinical intent summary, and acceptance confirmation — feeding directly into the clinical safety hazard log.

- Integrate with both organisations’ clinical systems — the MVRT record must be visible in both the sending and receiving organisation’s EPR, not trapped in a third-party coordination layer that neither clinical governance team can audit.

The cascade effect: why one unconfirmed handover breaks every downstream flow

In the previous article, we described how the Seven Flows interact through cascading failure logic. MVRT sits at a critical point in this chain.

If Alert & Responsibility fails — if the receiving organisation has not explicitly accepted responsibility — then two downstream consequences follow.

First, Service Routing is compromised. If no one has accepted responsibility, routing decisions are being made by the sending organisation (which may not understand the receiving organisation’s capacity, capability, or triage criteria) rather than by the receiving organisation (which should be making the clinical judgement about how to allocate the patient within their service). Routing without acceptance is routing without accountability.

Second, and more consequentially, the Outcome flow is structurally broken. If no one has formally accepted responsibility for a patient at a boundary, there is no accountable party from whom outcome data can be expected. The feedback loop that should tell the originating clinician “here is what happened after you referred this patient” has no one to complete it. The boundary becomes a one-way door.

This cascade means that an MVRT failure doesn’t just affect one dimension of boundary governance. It structurally undermines the entire downstream chain. A neighbourhood centre where MVRT is not enforced is a centre where outcomes cannot be measured at the boundary level — which means the centre has no mechanism for learning whether its internal boundaries are safe.

What this means for the 43 NNHIP pioneer sites

The neighbourhood health implementation programme is overseen by a taskforce chaired by Sir John Oldham, with four enabler groups covering data/digital, finance, estates, and workforce. NHS England London’s targeted operating model calls for “protocols for shared care and handovers” and “clinical accountability plans for every INT.”

MVRT is what those protocols must achieve. The question for every NNHIP site is not “do we have a handover process?” — most will have something, even if informal. The question is: “At every organisational boundary within our neighbourhood, can we demonstrate that clinical responsibility transfers bilaterally, with confirmed acceptance, infrastructure enforcement, clinically-timed escalation, and an auditable trail?”

If the answer is no — and for the vast majority of neighbourhood models currently being designed, it will be no — then the centre is operating with a structural blind spot at the most safety-critical dimension of boundary governance.

This is not about bureaucracy. It is about the principle that when a patient’s care moves between organisations, someone is always accountable. Always. Without exception. The aviation industry solved this by making it structurally impossible for an aircraft to be unowned. Healthcare needs to make it structurally impossible for a patient to be unowned.

The infrastructure to enforce this needs to be designed into neighbourhood health centres before they open — not retrofitted after the first serious incident at an internal boundary reveals that the corridor conversation model has no governance underneath it.

Private healthcare has the same MVRT requirement

MVRT applies identically outside the NHS. When a private hospital discharges a patient to their GP, the same structural gap exists. When a private insurer’s pre-authorisation process sits between a clinician’s request and a patient’s treatment, the same governance vacuum can form. When a PE-owned hospital group integrates multiple providers, the internal boundaries carry the same MVRT risk — often with less standardised infrastructure than the NHS provides.

The principle is universal: wherever clinical responsibility crosses between organisations, the transfer must be explicit, bilateral, confirmed, and infrastructure-enforced. The organisational form — NHS, private, voluntary, digital — is irrelevant. The patient’s right to have someone accountable for their care does not change because the boundary is between two private providers rather than between an NHS Trust and a GP practice.

The next article in the Architecting for Neighbourhood Health series examines the constitutional complexity of co-located care — what happens when a neighbourhood health centre contains four or five fundamentally different types of organisation, each governed by different legislation, different regulators, and different institutional purposes, all sharing a building and a patient population.

Architecting Neighbourhood Health Series

- What the Implementation Programme Is Missing

- Mapping the Seven Flows in a Neighbourhood Health Centre

- Clinical Responsibility Transfer — Why Handover Frameworks Don’t Cross Organisational Boundaries (current)

- Constitutional Complexity — Five Organisations, Five Legal Frameworks, One Building

- Boundary Readiness — Why “People, Process, Technology” Fails at Healthcare Boundaries

- The Legal Pillar — Data Sharing, Contractual Frameworks, and Constitutional Compliance

- The Clinical Safety Pillar — When the Hazard Sits Between Organisations

- The Process Pillar — Crossing Choreography and the Pre-Conditions Nobody Defines

- The People Pillar — Why Generic MDT Training Doesn’t Cross Organisational Boundaries

- The Technology Pillar — Why Interoperability That Doesn’t Preserve Governance Is Interoperability in Name Only

Inference Clinical’s Seven Flows Boundary Governance Audit assesses MVRT compliance at every organisational boundary, with cascading failure logic that reveals structural dependencies invisible to internal governance. Constitutional transition analysis identifies where cross-domain boundaries carry enhanced MVRT risk. To understand where your patients may be most vulnerable, book a scoping call.