Key Takeaways

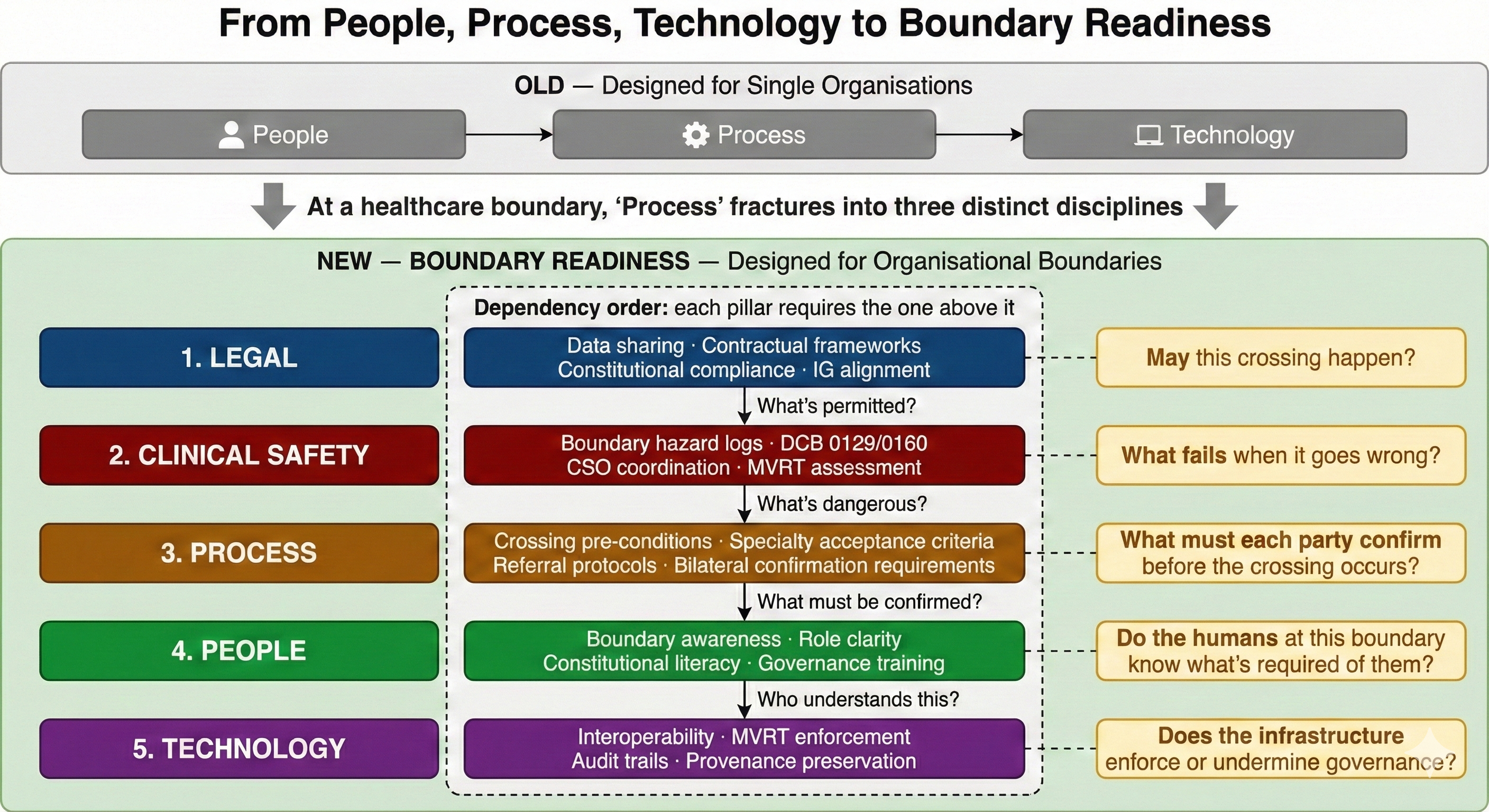

- People, Process, Technology was designed for transformation within a single organisation — neighbourhood health is a transformation across organisational boundaries, and PPT’s three pillars are structurally insufficient.

- “Process” at a healthcare boundary conceals three fundamentally different disciplines: legal architecture (data sharing, IG), clinical safety architecture (hazard logs, DCB 0129/0160, CSO coordination), and boundary crossing choreography (specialty-specific pre-conditions).

- The Boundary Readiness model replaces PPT with five pillars — Legal, Clinical Safety, Process, People, Technology — each independently assessed, each with its own expertise, each answerable to its own authority.

- The pillars have a dependency order — Legal first, Technology last — directly challenging the implementation programme’s digital-first approach. Technology deployed before legal architecture is in place enables ungoverned data flows.

- Each bilateral boundary within a neighbourhood must be assessed against all five pillars before the first patient walks through the door — and reassessed whenever the organisational landscape changes.

This is the fifth article in the Architecting for Neighbourhood Health series. The first article examined why the current governance conversation addresses committee structures but not boundary governance. The second introduced the Seven Flows that must function at every organisational crossing. The third went deep on clinical responsibility transfer and the MVRT principle. The fourth examined constitutional complexity — what happens when fundamentally different types of organisation share a building and a patient population.

Every transformation programme in the NHS eventually reaches for the same model. People, Process, Technology. The golden triangle. Attributed to Harold Leavitt’s 1964 Diamond Model, popularised by Bruce Schneier in the 1990s, and applied to every IT-enabled change programme since. Train the people. Fix the processes. Deploy the technology. If the triangle is balanced, the transformation succeeds.

The neighbourhood health implementation programme follows the same pattern. Its four enabler groups — data/digital, finance, estates, workforce — map almost directly onto PPT thinking. Technology (data/digital), process (finance, estates), people (workforce). The 10 Year Health Plan describes a shift from hospitals to communities, from analogue to digital, from treatment to prevention. The enablers are designed to make that shift happen. They are necessary. They are also insufficient — because PPT was designed for transformation within a single organisation, and neighbourhood health is a transformation across organisational boundaries.

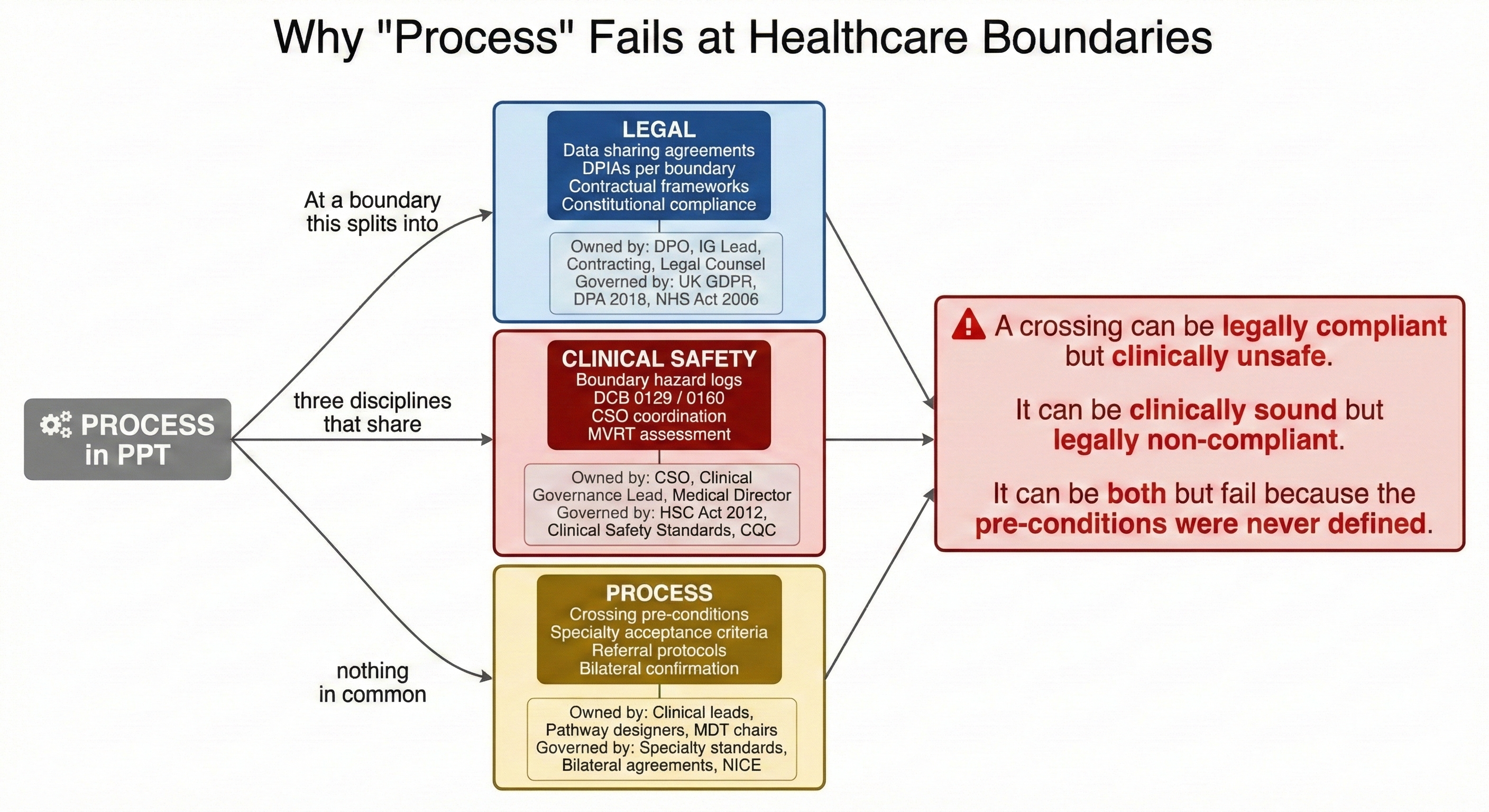

At a boundary between two healthcare organisations, “Process” is not one thing. It conceals three fundamentally different disciplines, governed by different frameworks, requiring different expertise, answerable to different authorities. Collapsing them into a single category is the structural reason why boundary governance fails.

What is Boundary Readiness?

Boundary Readiness is a five-pillar governance framework designed for healthcare organisational boundaries. It replaces People, Process, Technology with Legal, Clinical Safety, Process, People, Technology — assessed in dependency order at every bilateral boundary between co-located organisations. The model recognises that PPT’s “Process” conceals three distinct disciplines at a healthcare boundary, and that technology must implement governance requirements defined by the preceding four pillars, not the reverse.

What PPT’s “Process” hides at a neighbourhood health boundary

In a standard PPT model, “Process” covers how work gets done. Workflows, standard operating procedures, escalation pathways, reporting structures. Within a single organisation, these are unified under a single governance framework. The same board approves them. The same quality team audits them. The same risk register captures their failures.

At a healthcare boundary, “Process” fractures into three distinct domains.

The first is legal architecture. Data sharing agreements between independent data controllers. Data Protection Impact Assessments for cross-boundary data flows. Contractual frameworks that define what each organisation is obligated to provide. Information governance that determines which legal basis permits the sharing of patient data across a specific organisational boundary. The legal architecture of a boundary is the province of information governance leads, data protection officers, contracting teams, and legal counsel. It is governed by UK GDPR, the Data Protection Act 2018, the NHS Act 2006, and whatever contractual framework sits between the organisations.

The second is clinical safety architecture. Hazard logs that capture risks at the boundary between organisations. Clinical risk management processes compliant with DCB 0129 and DCB 0160. Clinical Safety Officer coordination across organisations that each have their own CSO. Incident reporting pathways for events that occur at a boundary rather than within either organisation. The clinical safety architecture of a boundary is the province of Clinical Safety Officers, clinical governance leads, and medical directors. It is governed by the Health and Social Care Act 2012, the clinical safety standards, CQC registration requirements, and professional regulatory obligations.

The third is boundary crossing choreography — the specific pre-conditions that must be satisfied before a particular type of crossing can validly occur. What must a GP confirm before a Local Authority safeguarding team can accept a referral? What investigations must be complete before a cardiologist will accept a cardiology referral? What information must accompany a discharge before a GP can meaningfully accept responsibility for a patient’s ongoing care? These pre-conditions are different for every crossing type — defined by the combination of who is sending, who is receiving, and what type of clinical or governance interaction is taking place.

These three domains share a boundary. They do not share a discipline. The DPO and the CSO have different training, different professional backgrounds, different regulatory obligations, and different reporting lines. Neither of them defines the clinical pre-conditions that a cardiologist requires before accepting a GP referral — that is a clinical governance question answered by specialty-specific acceptance criteria, referral protocols, and bilateral agreements between provider organisations.

A process that is legally compliant can be clinically unsafe. A process that is clinically sound can be legally non-compliant. And a crossing where both the legal framework and the clinical safety assessment are in place can still fail because the specific pre-conditions for that crossing type have never been defined — the GP refers without the investigations the specialist needs, the discharge arrives without the information the GP requires, the safeguarding referral lacks the specific detail the LA’s MASH team needs to act.

PPT collapses all three into “Process” and assumes that fixing one fixes the others. At a healthcare boundary, they must be assessed, governed, and assured independently.

The Boundary Readiness model: five pillars for healthcare boundary governance

Inference Clinical’s Boundary Readiness model replaces PPT’s three pillars with five, designed specifically for healthcare boundary governance:

Legal. Clinical Safety. Process. People. Technology.

This is not an incremental extension of PPT. Others have added fourth pillars — Data, Operations, Culture. A recent paper in Nature Digital Medicine proposes PPTO (People, Process, Technology, Operations) for AI governance in healthcare. These additions keep “Process” intact and bolt something alongside it. The Boundary Readiness model does something different: it breaks PPT’s “Process” apart into the three disciplines that healthcare boundaries actually require — Legal, Clinical Safety, and Process — each independently assessed, each with its own expertise, each answerable to its own authority.

Pillar 1: Legal — may this crossing happen?

The Legal pillar asks whether the boundary crossing is lawfully permitted. This means mapping data sharing agreements, contractual obligations, constitutional compliance, and regulatory alignment for each organisational crossing. Without legal architecture, every subsequent pillar operates on unlawful ground. The Legal pillar is owned by data protection officers, information governance leads, and contracting teams. It is governed by UK GDPR, the Data Protection Act 2018, the NHS Act 2006, and the specific contractual framework between the organisations at each boundary.

Pillar 2: Clinical Safety — what fails when this crossing goes wrong?

The Clinical Safety pillar asks what hazards exist at this specific boundary. This means boundary-specific hazard identification, DCB 0129/0160 compliance for cross-boundary digital systems, CSO coordination across organisations, and MVRT infrastructure assessment. A crossing that is legally compliant can still be clinically unsafe — the data sharing agreement may permit the flow, but the hazard log may not have captured what happens when the flow is delayed, incomplete, or misinterpreted at the receiving end. The Clinical Safety pillar is owned by Clinical Safety Officers, clinical governance leads, and medical directors.

Pillar 3: Process — what must each party confirm before the boundary is crossed?

The Process pillar — now stripped of the legal and clinical safety dimensions that PPT bundled into it — focuses on the specific pre-conditions for each crossing type. A GP-to-cardiologist referral has different pre-conditions from a GP-to-safeguarding referral. A discharge from community Trust to GP practice has different pre-conditions from a discharge from mental health Trust to GP practice. The Process pillar defines what must be confirmed, by whom, and in what form before each specific crossing type can validly occur. It is owned by clinical leads in both the sending and receiving organisations, and it is governed by specialty-specific acceptance criteria, referral protocols, and bilateral agreements.

Pillar 4: People — do the humans at this boundary know what governed crossing requires?

The People pillar asks whether the individuals who work at or across a boundary understand the governance architecture they operate within. This is not generic “change management” or Prosci ADKAR-style adoption training. It is specific to the boundary: does the GP receptionist who triages incoming referrals know the different acceptance criteria for each organisation in the building? Does the community nurse who escalates a safeguarding concern know the constitutional pathway that a safeguarding referral must follow — Local Authority, not the mental health practitioner in the next room? Does the social prescriber know which data they can share with the GP practice under the bilateral DSA, and which they cannot? People readiness at a boundary is knowledge of the specific legal framework, safety requirements, and crossing pre-conditions at the particular boundaries each individual works across.

Pillar 5: Technology — does the infrastructure enforce or undermine boundary governance?

The Technology pillar asks whether digital infrastructure enforces the governance requirements that the first four pillars define. Does the referral system enforce bilateral confirmation — MVRT — or does it permit fire-and-forget transfers? Does the clinical system preserve provenance when information crosses from one data controller to another? Does the audit trail capture which organisation’s governance framework applied at each step? Technology that enables data sharing without enforcing the legal, clinical safety, process, and people requirements defined by the preceding four pillars is not an enabler — it is a risk multiplier. It allows ungoverned crossings to happen faster, at greater scale, and with less visibility than manual processes.

PPT vs Boundary Readiness: a healthcare transformation framework comparison

| Aspect | PPT Approach | Boundary Readiness Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Scope | Single organisation | Every bilateral boundary between organisations |

| Process | Unified — one governance framework | Fractured into Legal, Clinical Safety, and Process — each with its own authority |

| Technology role | Enabler — deployed to accelerate transformation | Enforcer — deployed last to enforce the governance defined by the four pillars above it |

| Dependency | Three equal pillars — addressed in any order | Five pillars in strict dependency order — Legal first, Technology last |

| Failure model | Averaged — strong in two pillars can compensate for weakness in the third | Cascading — failure in any pillar fails all pillars beneath it |

| Assessment unit | The organisation | Each bilateral boundary (10 boundaries in a 5-org neighbourhood) |

Why the dependency order matters: Legal first, Technology last

The five pillars are not a checklist to be addressed in any order. They have a dependency structure. Each pillar requires the one above it to be in place before it can function.

Legal comes first because without it, every subsequent pillar operates on unlawful ground. A clinical safety assessment of a boundary crossing is meaningless if the crossing itself is not legally permitted. Process pre-conditions are academic if the data sharing agreement that permits the exchange has not been signed. People training is premature if the legal framework they are being trained on has not been established. Technology deployment is premature — and potentially harmful — if the legal architecture it should enforce does not yet exist.

Clinical Safety comes second because it identifies the hazards that the remaining pillars must address. The process pre-conditions for a crossing should reflect the hazards identified in the clinical safety assessment. People training should include awareness of the specific hazards at their boundaries. Technology should be designed to mitigate the hazards, not merely to enable the data flow.

Process comes third because it translates the legal permissions and clinical safety requirements into specific, actionable pre-conditions for each crossing type. These pre-conditions are what people need to be trained on and what technology needs to enforce.

People comes fourth because individuals cannot be trained on boundary governance requirements that have not yet been defined. Generic training on “working in multidisciplinary teams” is not People readiness. Specific training on “the legal basis, clinical safety requirements, and process pre-conditions at the particular boundaries you work across” is.

Technology comes last because its role is to enforce the governance requirements defined by the preceding four pillars. Technology deployed before those requirements are defined enables ungoverned data flows — which is worse than no data flow at all, because it creates the illusion of governance without the substance.

This dependency order directly challenges the neighbourhood health implementation programme’s digital-first approach. The data/digital enabler group is one of the first to mobilise. Shared care records, integrated referral pathways, population health dashboards — all are being developed and procured before the legal architecture at each bilateral boundary has been established, before the clinical safety assessment of each boundary has been completed, before the process pre-conditions for each crossing type have been defined, and before the people who will work at those boundaries have been trained on the governance requirements they must follow.

The result is predictable. Technology enables crossings that the governance architecture has not sanctioned. Data flows across boundaries without bilateral DSAs. Referrals are sent electronically without the pre-conditions that the receiving organisation requires. Audit trails capture the technical event but not the governance context. And when something goes wrong at a boundary, neither organisation can demonstrate that the crossing met the governance requirements — because those requirements were never formally defined.

Applying Boundary Readiness to the 43 NNHIP pioneer sites

The 43 New Neighbourhood Health Improvement Programme pioneer sites announced in 2025 are the first real-world test of neighbourhood co-location at scale. Each site will bring together some combination of general practice, community health services, mental health, pharmacy, and voluntary sector — the five constitutional domains explored in the previous article.

Applying the Boundary Readiness model to these sites reveals the scale of the governance task. A five-organisation neighbourhood health centre has ten bilateral boundaries. Each boundary must be assessed against five pillars. That is fifty discrete governance assessments — not fifty checkboxes on a single form, but fifty assessments that each require specific expertise (legal, clinical safety, clinical process, workforce development, and digital) and each produce specific governance artefacts (DSAs, hazard logs, crossing protocols, training records, and technology compliance evidence).

No current governance framework mandates this assessment. The implementation programme’s governance guidance focuses on committee structures — neighbourhood boards, ICB oversight, provider collaborative governance. These are governance arrangements for decision-making. They are not governance arrangements for boundary crossing. The Boundary Readiness model addresses the gap: it provides a structured assessment of whether each bilateral boundary within a neighbourhood is governed to the standard that patient safety requires.

The 43 pioneer sites vary significantly in their organisational composition, their digital maturity, and their existing governance infrastructure. Some have existing co-located services with informal governance arrangements. Others are building from scratch. The Boundary Readiness model provides a common assessment framework that works regardless of the starting position — because it assesses the governance at each boundary independently, rather than applying a blanket governance standard across the whole neighbourhood.

What the neighbourhood governance board must require

The governance board for each neighbourhood health centre — whether it sits within the SNP contract holder, the ICB, or a dedicated neighbourhood governance structure — must require evidence of Boundary Readiness at every bilateral boundary. At minimum:

- Legal readiness confirmed per boundary — signed bilateral DSAs, completed DPIAs, constitutional compliance assessment, and contractual framework defining cross-boundary obligations for each organisational crossing.

- Clinical Safety assessment complete per boundary — boundary-specific hazard log, DCB 0129/0160 compliance for cross-boundary digital systems, CSO coordination mechanism operational, MVRT infrastructure assessed.

- Process pre-conditions defined per crossing type — documented acceptance criteria for each referral, discharge, and handover type that crosses an organisational boundary, agreed bilaterally by the sending and receiving organisations.

- People trained on boundary-specific governance — not generic MDT training, but specific knowledge of the legal framework, safety requirements, and crossing pre-conditions at the particular boundaries each individual works across.

- Technology assessed for governance enforcement — confirmation that digital infrastructure enforces bilateral confirmation (MVRT), preserves provenance across systems, and produces auditable governance artefacts at every boundary.

- Reassessment triggers defined — documented criteria for when Boundary Readiness must be reassessed: new organisations joining, SNP contract changes, digital system upgrades, clinical pathway redesign, or significant incident at a boundary.

From analysis to architecture: a practitioner framework for neighbourhood boundaries

The Boundary Readiness model is not an academic framework. It is a practitioner tool designed to be applied at specific bilateral boundaries by specific governance professionals. The Legal pillar is assessed by IG leads and DPOs. The Clinical Safety pillar is assessed by CSOs and clinical governance leads. The Process pillar is assessed by clinical leads in both organisations. The People pillar is assessed by workforce development and training leads. The Technology pillar is assessed by digital leads and clinical safety officers together — because technology at a boundary is a clinical safety question, not just a digital question.

Each pillar produces specific governance artefacts. The Legal pillar produces signed DSAs, completed DPIAs, and constitutional compliance assessments. The Clinical Safety pillar produces boundary-specific hazard logs, DCB 0129/0160 compliance evidence, and CSO coordination minutes. The Process pillar produces bilateral crossing protocols with specific pre-conditions for each crossing type. The People pillar produces training records showing that individuals understand the governance requirements at their specific boundaries. The Technology pillar produces compliance evidence showing that digital infrastructure enforces the governance requirements defined by the preceding four pillars.

These artefacts are not filed and forgotten. They are living governance documents that must be reviewed whenever the organisational landscape changes — a new organisation joins the neighbourhood, an SNP contract is renegotiated, a digital system is upgraded, a clinical pathway is redesigned, or a significant incident occurs at a boundary. The reassessment triggers are themselves a governance artefact, defined at the time of initial assessment and maintained as the neighbourhood evolves.

The Boundary Readiness model also has a cascading failure logic. If the Legal pillar fails at a boundary — the DSA is unsigned, the DPIA is incomplete, the constitutional compliance assessment has not been done — then every pillar beneath it is automatically assessed as “not ready,” regardless of their individual status. A boundary with excellent clinical safety assessment, well-defined process pre-conditions, trained staff, and compliant technology is still not boundary-ready if the legal architecture is not in place. The dependency order is enforced, not advisory.

This cascading logic is what distinguishes Boundary Readiness from a simple maturity model. Maturity models allow organisations to score well in some dimensions while acknowledging weakness in others — and to declare overall progress based on the average. Boundary Readiness does not permit averaging. A boundary is either ready at every pillar or it is not ready. The weakest pillar is the boundary’s readiness score, and if the weakest pillar is Legal, every pillar beneath it inherits the failure regardless of its own assessment.

For the 43 pioneer sites and for every neighbourhood health centre that follows, Boundary Readiness provides the governance architecture that the implementation programme needs but has not yet defined. It is the bridge between the Seven Flows (what must function at every boundary) and the operational governance (how each boundary is assessed, governed, and assured). It replaces PPT’s three-pillar model with one designed for the constitutional, clinical, and operational complexity of healthcare organisational boundaries.

A better digital transformation model for Integrated Care Systems

The Boundary Readiness model is not only a governance tool. It is a change management framework for NHS digital transformation that works where PPT does not — at the joins between organisations. Integrated Care Systems are built on the premise that organisations collaborate across boundaries. The ICS Framework assumes this collaboration can be enabled through workforce planning, digital investment, and process standardisation. Boundary Readiness adds the structural layer that ICS governance currently lacks: a per-boundary assessment that treats legal architecture, clinical safety, process choreography, people readiness, and technology enforcement as independently governed disciplines, each requiring its own expertise and producing its own assurance evidence.

For programme directors leading neighbourhood health implementation, this means the traditional transformation playbook — define the vision, train the workforce, deploy the technology — must be supplemented with a boundary-by-boundary governance assessment that respects the constitutional complexity of multi-organisational co-location. The Boundary Readiness model provides that assessment. It is the missing layer between strategic intent and operational safety.

The next article in the Architecting for Neighbourhood Health series examines the Legal pillar — the foundational layer of Boundary Readiness. Data sharing agreements, DPIAs, dual legal basis mapping, Caldicott Guardian coordination, and contractual alignment at every bilateral boundary. Legal is first because without it, everything built on top is unlawful.

Architecting Neighbourhood Health Series

- What the Implementation Programme Is Missing

- Mapping the Seven Flows in a Neighbourhood Health Centre

- Clinical Responsibility Transfer — Why Handover Frameworks Don’t Cross Organisational Boundaries

- Constitutional Complexity — Five Organisations, Five Legal Frameworks, One Building

- Boundary Readiness — Why “People, Process, Technology” Fails at Healthcare Boundaries (current)

- The Legal Pillar — Data Sharing, Contractual Frameworks, and Constitutional Compliance

- The Clinical Safety Pillar — When the Hazard Sits Between Organisations

- The Process Pillar — Crossing Choreography and the Pre-Conditions Nobody Defines

- The People Pillar — Why Generic MDT Training Doesn’t Cross Organisational Boundaries

- The Technology Pillar — Why Interoperability That Doesn’t Preserve Governance Is Interoperability in Name Only

Inference Clinical’s Seven Flows Boundary Governance Audit operationalises the Boundary Readiness model — assessing all five pillars at every organisational boundary, with cascading failure logic, constitutional transition mapping, and MVRT compliance scoring. To assess your Boundary Readiness before your neighbourhood health centre opens, book a scoping call.