Inference Clinical's Seven Principles of Safe Infrastructure Engineering

How we build systems that remain safe, accountable, and improvable over decades.

When systems affect health, autonomy, or safety, engineering choices are ethical choices. These principles govern how Inference Clinical builds software. They apply whether they are convenient or not.

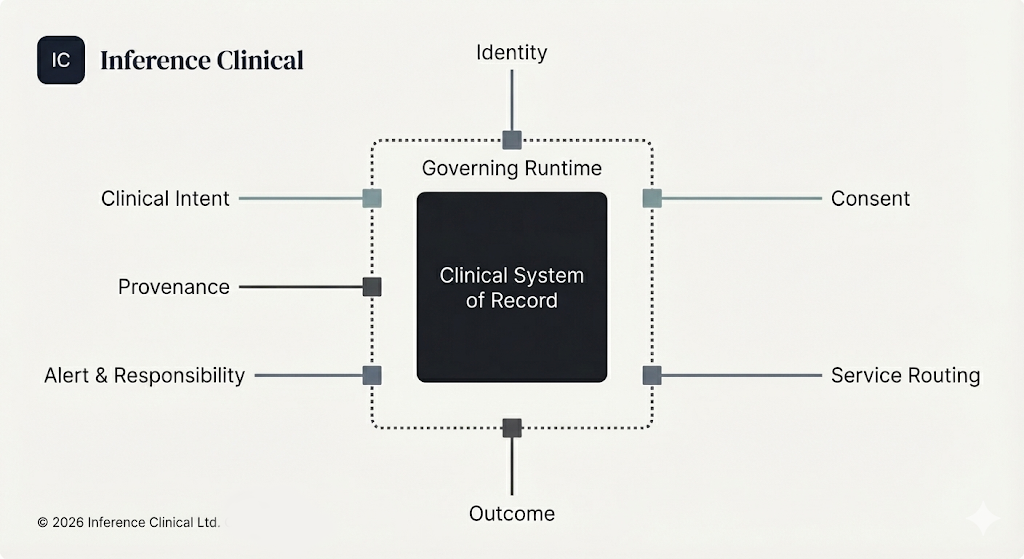

The Invariant System Model

Clinical systems do not fail because teams lack principles. They fail because critical dependencies are left implicit until they break under pressure.

Before we describe how we engineer, we make explicit what any safety-critical clinical system must preserve, regardless of vendor, technology, or delivery method.

These are not values or aspirations. They are structural flows that exist whether acknowledged or not.

Seven flows that must remain coherent for a clinical system to be safe, governable, and accountable

Each flow can be implemented in many ways. The dependency structure cannot.

When these relationships are implicit, systems drift. When they are explicit, systems can change without losing control.

The Seven Flows describe the structure of the problem. Our engineering principles describe how we work within it.

Our engineering discipline within these constraints.

Systems are long-lived, even when projects are not

We design on the assumption that systems will outlast funding cycles, vendors, teams, and technologies.

- Architecture must age well

- Knowledge must accumulate, not reset

- Ownership must be continuous

A system designed to be "finished" is already decaying.

Safety is a runtime property, not a sign-off event

We do not equate safety with approval gates, documentation milestones, or ceremonial reviews.

- Safety is enforced continuously

- Violations are prevented where possible

- Evidence is generated as the system operates

If safety cannot be observed at runtime, it does not exist.

If a system permits unsafe behaviour, it will eventually occur

Policies that rely on training, process compliance, or good intentions will fail under pressure.

- Constraints must be technical, not procedural

- Policy must be executable, not advisory

- Unsafe states should be difficult or impossible to express

The right abstraction reduces harm

Abstractions are safety mechanisms.

We design SDKs, schemas, and protocols to reduce cognitive load, prevent category errors, and encode invariants at the point of use.

Complexity is not neutral. Poor abstraction transfers risk to humans.

Small, reversible change is safer than careful delay

We reject the idea that slowness equals safety.

- We design for small, incremental change

- We prefer reversibility over certainty

- We monitor continuously and respond early

Delay concentrates risk. Iteration disperses it.

Evidence is a first-class system output

A system is incomplete if it cannot explain what happened, why it happened, under whose authority, and with what consent.

Evidence is not paperwork. It is an operational responsibility of the system itself.

Engineering is a moral discipline

When systems affect health, autonomy, or safety:

- Engineering choices are ethical choices

- "It worked as designed" is not a defence

- Responsibility cannot be delegated to tools, vendors, or process

We accept accountability for the consequences of the systems we build.